You know him as Grandpa Walton. What you may not know is that actor, activist, and gardener Will Geer has a major backstory.

In the midst of a successful New York stage, film, and radio career in the mid-1950s, he was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee and blacklisted.

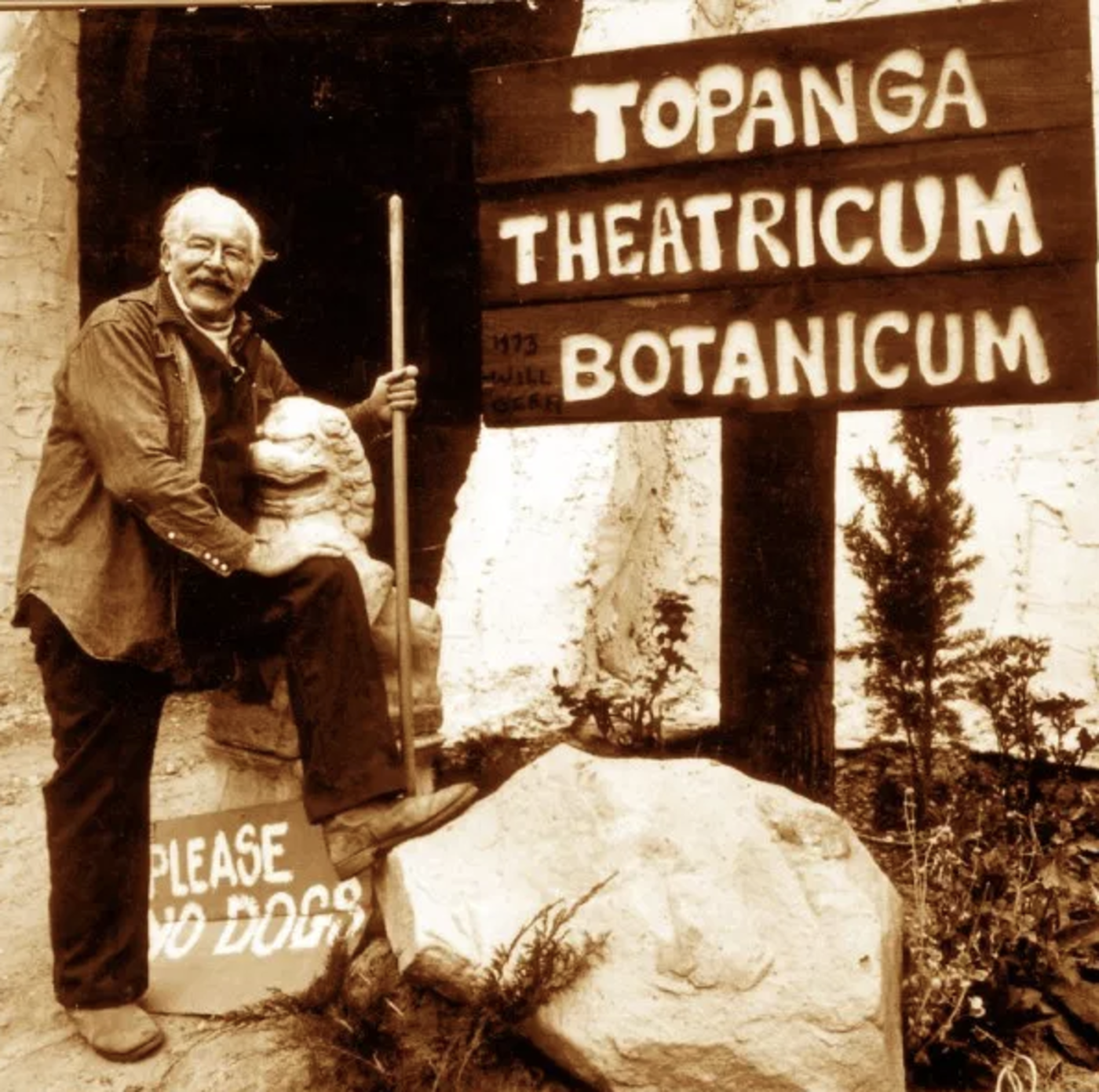

He moved his wife and family to LA’s Topanga Canyon, began growing flowers, vegetables, and herbs, and founded a community theater known as Theatricum Botanicum (literally, “Garden Theater”), initially for other blacklisted actors, playwrights, and folk singers.

In 1973, Geer began his successful run with the popular TV series “The Waltons.” He and his wife, actor Herta Ware, established a nonprofit, expanded the theater, and became known, among other things, for their staging of Shakespeare plays.

Geer died in 1978, but his family has carried on. Under the artistic direction of his daughter, Ellen Geer, the theater now offers an annual summer season of five repertory plays, as well as year-round classes to actors of all ages. They host live music concerts, nurture fledgling playwrights, and reach out to schools and students across LA County.

And once a year they pay tribute to one of their dearest friends and greatest heroes: folk singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie.

This year the date was October 6. The venue is right on Topanga Boulevard, about halfway between the 101 and PCH. You can pay $7 to park or you can street-park along the guardrail for free. You can bring a picnic, wander around a bit, and find a place to eat, or you can buy drinks and a bite to eat at The Elephant, the TB’s on-site snack bar.

The musicians, many of them members of the extended Geer family, played, sang, and took turns telling the story of Guthrie’s life: the Oklahoma childhood, the sister Clara who set her clothes on fire and died when Guthrie was 7, the mother who went insane (she drank but may also have been suffering from undiagnosed Huntington’s disease) and was carted off to the asylum.

Instruments included guitar, flute, harmonica, dulcimer, cello, banjo, fiddle, washtub bass, and washboard. That a few of the voices veered toward older, cracked and quavering, only added to the down-home, old-timey feel.

“This train is bound for glory.”

“If I had wings like Norah’s dove.”

“Keep your hand on that plow.”

Many of us looked to need help walking, never mind plowing a field, but no matter. For us children of the 1960s and ’70s, these were the songs of our youth, the anthems we were going to be singing as we ushered in an era of peace and love such as the world had never before known.

Woody started singing on one or two watts Texas radio stations. Outside, the dust started blowing. He left his family and headed west with the Okies.

Hard traveling, hard fighting, hard sweating.

“Have you seen that vigilante man?”

“If you ain’t got the do re mi.”

The performers urged us to sing along but the crowd, though friendly and receptive, seemed a little tired.

“You can’t scare me, I’m sticking with the union,” we mouthed, while the guy next to me sucked on a clandestine can of beer.

Guthrie’s life was marked by tragedy, poverty, and illness. He married three times and had eight children. He traveled incessantly.

Will Geer and his wife were friends from way back. They invited him to sleep on their couch in New York for a bit in the early ’40s, right around the time Geer was doing “Tobacco Road” on Broadway.

World War II came along. “What were their names, tell me what were their names?”

The FDR era followed: “Roll on Columbia, roll on.”

Inevitably, we came to “This Land is Your Land,” Guthrie’s most well-known song. I haven’t felt that sad in a long time.

I thought of how, dog-eared copy of “On the Road” in hand, I’d hitchhiked in my early 20s up and down the Eastern seaboard and at one point to Southern California. I thought of how, in spite of our youthful political ideals, not a whole lot had changed.

In 1945, Guthrie was drafted. When he came home, his beloved 4-year-old daughter Cathy died in a house fire. In 1962, his oldest son Bill died at 23 in a car accident. Meanwhile, he became afflicted with Huntington’s disease, a crippling and fatal nerve disorder (they left out the rampant alcoholism, but that’s OK).

Guthrie left his second wife and went to California. Just outside Theatricum Botanicum’s main stage stands the rustic wooden structure where he stayed and that is still known as “Woody’s Shack.” He married a third time, moved to Florida, burned his arm in a campfire explosion — he could no longer play the guitar — and died in 1967 at the age of 55.

So long, it’s been good to know you.

And may Will Geer’s descendants, and all at the Theatricum Botanicum, continue to sing, play, and fight the good fight.

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books. For more, visit heather-king.com.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!