The International Printing Museum, located at 315 W. Torrance Blvd., Carson, is open Saturdays only, 10-4. I visited on an open house day that culminated in the screening of the documentary “Endless Letterpress.”

The spot is a throwback to another era. First, the smell: a homey combination of ink, paper, and wood, grandmother’s attic. Older guys in vests, newsboys’ visors, and denim aprons feed paper into hand-cranked presses.

Lining the walls are grainy black and white photos of printing press days gone by. Stacks of narrow, long wooden drawers are filled with lead slugs of type: Roman, Antique, Gothic.

The museum hosts frequent events. “Inside the Box: Clamshell Boxes and Antiquarian Books”; “Krazy Krafts Day” for the kids.

They’re trying to raise $20,000 to save a rare 1905 Heidelberg Cylinder Press, one of eight in the world. (Don’t miss the annual International Printing Museum and Los Angeles Printers Fair, which this year will take place over the course of the weekend of October 19-20.)

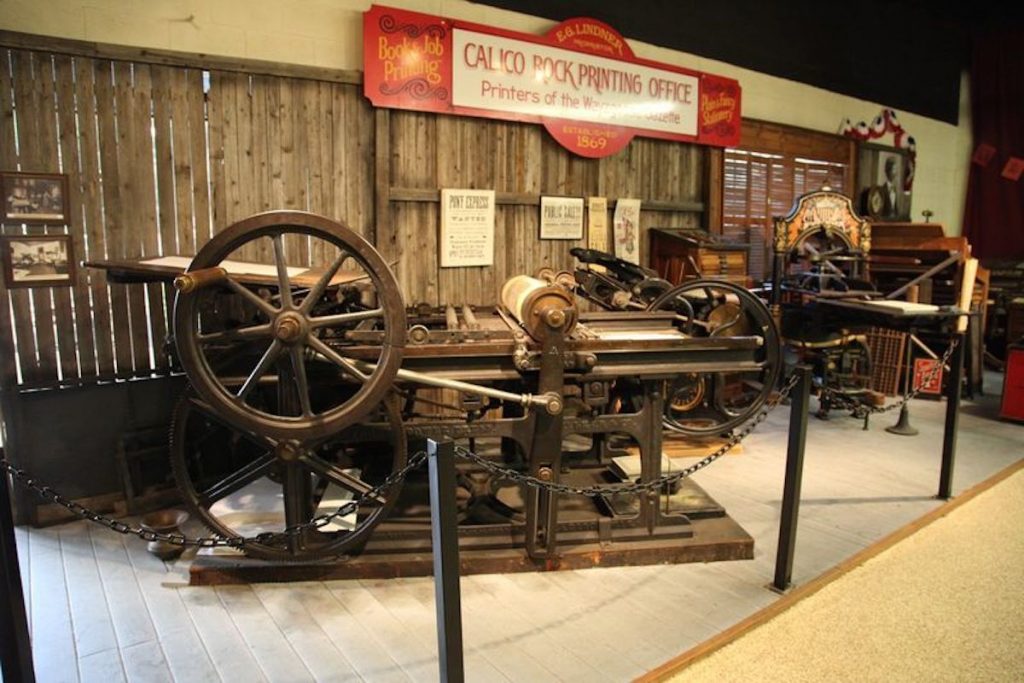

But the heart of the museum consists in its Ernest A. Lindler Collection, touted as “one of the world’s largest and finest collections of working antique presses.”

I merged into a tour in progress, led by Peter Small. We were just entering the Industrial Revolution (before that, presses were wooden), emblemized by an 1810 Stanhope metal press, made in England.

Snippets of info reeled by. The Columbian Hand Press was the first American-made metal press. The one owned by the museum is a beautiful object, topped by a painted cornucopia of vines, flowers, and fruit.

One kind of ink, used in composition rollers, was made by mixing glue and molasses. The mixture was temperamental, and as it turned out, much beloved by rodents.

The grasshopper press was invented circa 1878 by Enoch Prouty, a Baptist preacher who wanted to broadcast the evils of liquor. The Prouty Power Press featured a pair of bars that jumped up and down, a movement that uncannily resembled that of the long-legged garden insect.

In December 1881, the first edition of the Los Angeles Times was printed on one such press. Newspapers in those days were at the most four pages.

Other models include a C. Foster & Bro. Washington Hand Press (circa 1850), a LaTypote Stanhope Hand Press (circa 1850), a La Magand Card Press (circa 1900), from France, featuring a cranked flywheel, and a Model 1 Linotype Typesetting Machine (circa 1890).

Then there was the California Reliable Jobber Platen Press, which was used for smaller tasks such as handbills, posters, business cards, and stationery; the Rogers Typograph (circa 1895), combining typewriter and piano engineering; and the Howard Iron Works Paper Cutter (circa 1870).

The linotype machine was invented by Ottmar Merganthaler, a German-born inventor also known as “the second Gutenberg.” The museum owns a Linotype 5 Meteor (circa 1961). By 1980, these were obsolete.

We viewed an ad for Dr. Miles’ Nervine, a medicinal remedy with a very high alcohol content marketed to women during the early 1900s. World War II letterpress posters included “Save a loaf a week, help win the war.” “Order your coal now.” “Save wheat, meat, fats, sugar, and serve the cause of freedom.”

A nice lady made me an Art Deco logo of City Hall card, done on a Victorian parlor press, to take home. On sale at the front desk were a Neato Large Metal Harmonica, vintage postcards for a buck each, a quilled ink set ($5), and craft ink pads.

As we settled in for the film, “Los Ultimos” (“Endless Letterpress”), several genial folks circulated with bowls of free popcorn, candy, and snacks. Many of the viewers had obviously known one another for years.

The subject was the men who operate the last remaining letterpress in Buenos Aires. Printing is their vocation and, lack of fame and fortune notwithstanding, some had been at it for 50 years.

One guy, nearing 70, laughingly remarked about driving around town, “If I get in an accident it’s because I’m either looking at a woman or one of my posters. I don’t know if anyone cares as much as I do.”

Another, wearing a red shirt, solid black with ink up to his armpits, observed, “Young technicians don’t get dirty. They don’t. We’re the last idiots willing to get dirty.” A third printer, now retired, remembered, “If you hear the machine’s complaints, you’ll know what’s wrong with it.” Like monks, these men work in silence. They don’t even listen to the radio.

“This was handicraft. In the old days, one person could print a whole anarchist newspaper.” “New technologies are for the sake of speed. There’s nothing human about them.” “Given the current situation, we could say [letterpress] no longer exists.”

Now machines do everything. And hovering over the museum is the unvoiced question: Are we really any better for it?

A laminated card, prominently displayed near the front of the museum, says it best: “This is a Printing Office. Crossroads of Civilization. Refuge of all the Arts Against the Ravages of Time. Armoury of Fearless Truth Against Whispering Rumor. Incessant Trumpet of Trade.”

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books. For more, visit heather-king.com.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!