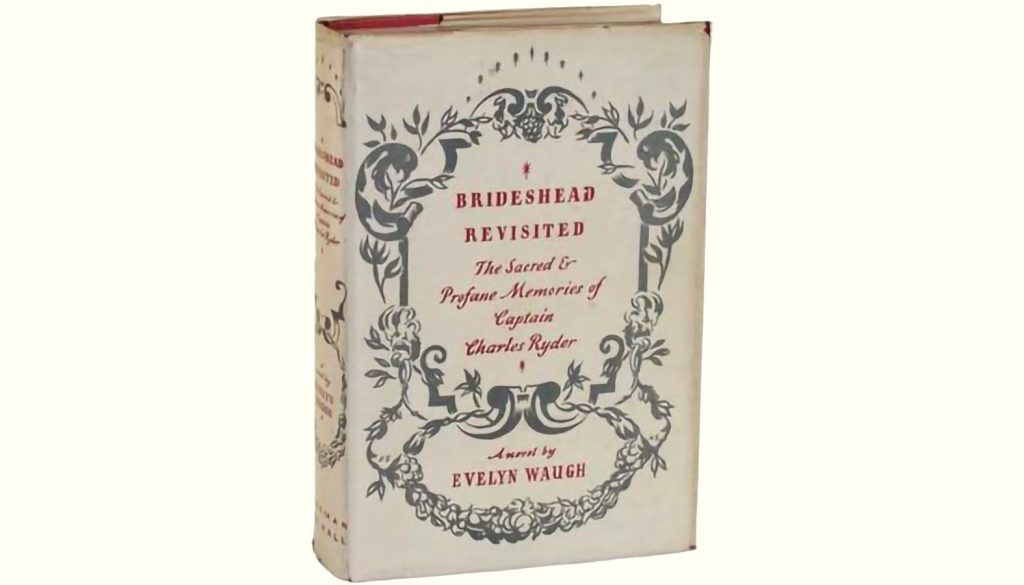

In the late spring of 1945, as World War II was drawing toward a close, a novel called “Brideshead Revisited” made its appearance in Britain; its first U.S. edition came out the following January.

Whatever else might be said of it — and a great deal has been said — three-quarters of a century later this book by Evelyn Waugh remains easily the most popular Catholic-themed work of fiction in the English language.

After all these years it is interesting to reflect on what accounts for the extraordinary success “Brideshead” has enjoyed from the start. The much praised 1981 TV miniseries based on it certainly helped, yet the novel itself still stands firmly on its own, occupying a special place in the affections of countless readers. Why?

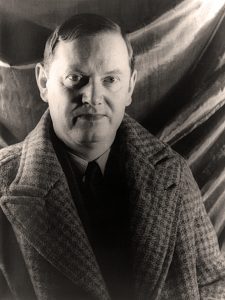

Before its publication, Waugh was best known for a series of biting satires puncturing the empty-headed pretensions of a decadent British upper class between the two world wars. They included such highly readable — and still read — volumes as “Decline and Fall,” “A Handful of Dust,” and “Scoop.”

“Brideshead Revisited” marked a new turn in the author’s career. The book’s romanticism and its richness of style touched exactly the right nerve in readers just emerging from the perils and privations of wartime and heading into a postwar era of uncertainty and (in Great Britain) austerity. Yet a novel about the foibles of a wealthy British Catholic family would seem at first glance to have little natural interest for most readers. So what was it that made — and for many still makes — “Brideshead” so very special?

Two things in particular seem to me to account for the book’s lasting appeal.

One is its nostalgia for happier times, especially strong in the story’s first section, which paints an idealized picture of undergraduate life at Oxford in the early 1920s. Several of the themes and characters introduced here take on darker hues as the story progresses, but the early days, as Waugh depicts them, are cloudless and golden. Although precious few people attended Oxford in the 1920s or any other time, Waugh’s idyllic version offers readers who ever went to any school any place a vicarious experience of carefree youth as they’d have liked it to be.

The second source of the book’s enduring popularity is, I think, its triumphalistic treatment of Catholicism. Waugh, a convert, makes being Catholic sound not just interesting but fashionable, delivering the message that the cleverest, most attractive, and ultimately most serious people are Catholics. It’s all summed up in the book’s great deathbed scene in which even the agnostic Charles Ryder, the story’s narrator, falls to his knees to pray for a sign of final repentance by the imperious, adulterous, lapsed Catholic Lord Marchmain.

Waugh was a brilliant stylist, but his writing in “Brideshead Revisited” has sometimes been criticized as being too self-indulgently lush. Perhaps so, yet this very lushness is part of the story’s attraction. And, as one critic remarked of Waugh, “however badly he writes, he always writes well.”

Among Waugh’s books, on the whole I prefer his World War II trilogy “Men at War,” and I also confess to having a soft spot in my heart for “The Loved One” — admittedly an odd reaction to so relentlessly ferocious an assault on American culture. But after 75 years, “Brideshead” holds a firm place in the esteem of very many readers, and it’s no stretch to think that may still be true 75 years from now. There are not too many books you can say that about.