ROME — Before “Who am I to judge?” and before the “throwaway culture,” as well as before his celebrated catalog of the 15 “spiritual diseases” of the Roman Curia, Pope Francis just three days after his election gave us the soundbite which, in many ways, would define his papacy.

“How I would like,” the new pope said, “a poor Church for the poor.”

Under the heading of “be careful what you wish for,” Pope Francis may now be perilously close to getting what he wanted, at least as far as the Vatican is concerned, not as a result of internal reform, but rather long-standing financial weaknesses combined with the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and its economic repercussions.

A recent internal analysis prepared for Pope Francis and the heads of Vatican departments suggests the Vatican’s deficit could balloon by as much as 175 percent in 2020, reaching $158 million, which is basically as much as the Vatican is projected to bring in this year, meaning it will be spending about twice as much as it collects.

Annual income for the Vatican (technically, the “Holy See”) derives from three principal sources: investment returns, the real estate market, and contributions from dioceses, all of which have been negatively affected by the coronavirus shutdowns.

Likewise, the Vatican City State, which fiscally is a separate operation, has been hard hit by closure of the Vatican Museums and the consequent loss of revenue from ticket sales.

Longer term, the Vatican faces a ticking financial time bomb in the form of unfunded pension obligations that’s not been ameliorated by the coronavirus, because even idled workers are still on the books.

Right now, the Vatican will have to scramble just to cover payroll; how it will make ends meet when more and more of its present workforce begins to retire and collect pension checks is, frankly, unknown.

The internal report recommended that Pope Francis impose a freeze on hiring and promotions, plus a ban on travel, even when it becomes possible again, as well as a moratorium on conferences and events.

Beyond that, it also counsels the creation of a unified investment fund for all Vatican entities to maximize return on investment, and at least hints at trimming payroll by recommending building a human resources capacity so a smaller staff can work more productively and nimbly.

In past eras of crisis, popes have been able to count on the generosity of Catholics around the world to provide the resources necessary to weather whatever storm broke.

Yet this time around things may be different, given that an important vehicle the Vatican uses to tap that generosity, the annual Peter’s Pence collection, has been tainted by association with a $225 million scandal involving the Vatican’s role in purchasing a former Harrod’s warehouse in London’s tony Chelsea neighborhood slated for conversion into luxury apartments.

Most Catholics believed Peter’s Pence was designed to support papal charities, and they may be less inclined to give if they think their money will instead end up in speculative land deals. The Vatican analysis presumes just a modest drop-off in income from the collection to support papal activities, and only time will tell if that’s right.

The crunch may well induce a new spirit of financial modesty, and to that extent, Pope Francis may be inclined to see it as a blessing in disguise. To date, his efforts at a financial cleanup have met with mixed results, but in the wake of the pandemic, it seems obvious some sort of reform is now inevitable.

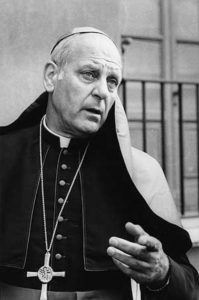

On the other hand, there’s also the wisdom embedded in the famous comment attributed to the late American Archbishop Paul Marcinkus, onetime president of the so-called “Vatican Bank,” which goes like this: “You can’t run the Church on Hail Marys alone.”

For the record, Archbishop Marcinkus always claimed he was misquoted. What he actually said, he insisted, was that when Vatican employees came to his office wanting their paychecks, he couldn’t respond, “I’ll pay you 400 Hail Marys instead.”

In whichever version, the point is the same: However much it may strive to be poor in spirit, the Vatican still needs money to keep things running.

It’s worth recalling, in that context, where Pope Francis was when he delivered the “poor Church for the poor” soundbite: The Vatican’s Paul VI Audience Hall, known to Italians as the “Aula Nervi” after the architect who designed it, Pier Luigi Nervi, whose other projects included the UNESCO building in Paris, Rome’s Fiumicino airport, and the Port Authority Bus Station in New York.

The hall was built between 1966 and 1971, providing seating for almost 7,000 people (capacity rises to 14,000 if people are standing) and features strong acoustics and lines of sight.

The total price tag at the time was about $6 billion in the old Italian lire, which worked out to $3.8 million in 1971. Adjusted for inflation over the intervening 50 years, in today’s money the same hall would cost about $25 million. Given its size and capacity, that’s hardly extravagant, but it’s not chump change either.

Yet if a pope is to be the Church’s chief evangelizer and a voice of conscience for the world, he needs a platform from which to speak. One of the reasons the “poor Church for the poor” line was so effective, in fact, was because Pope Francis delivered it in front of the entire world’s media, in a setting perfectly designed for it to get across, with great sound and broadcast facilities.

Pope Francis knows all this; when the London scandal broke, he acknowledged something seemed “dirty” about the affair, but defended on principle the idea of investing the Vatican’s income in order to grow its resources.

“Good administration isn’t about collecting the sum of the offerings and putting it in a desk drawer,” he said. “That’s bad administration. Instead, you have to try to make investments so that when you need money, it’s there.”

Thus the dilemma: How to embrace a new climate of limited means, along with much of the rest of the world, seeing it as an invitation to be that “poor Church” of the pope’s dreams, while, at the same time, cultivating practices of “good administration” to ensure that when the pope really needs it, he’s got more than Hail Marys in the account.