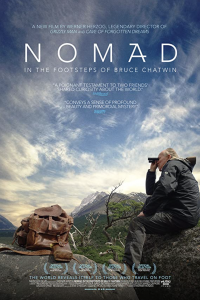

“Bruce Chatwin was a legendary adventurer and writer who died in 1989. Filmmaker Werner Herzog collaborated with Chatwin in the last years of his life. This film follows Herzog on a series of encounters inspired by Chatwin’s travels.”

So begins “Nomad: In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin,” the 2019 documentary by German filmmaker Werner Herzog.

Chatwin (1940-1989) is perhaps best known for the best-selling “The Songlines” (Penguin Books, $25.96). Part memoir, part fiction, part travelogue, part anthropology, the book explores the highly esoteric world of Aboriginal song as a way of charting and recording nomadic travel.

The globe-trotting legendary German filmmaker Herzog, now 78, has made more than 60 films about impossible dreamers, dying civilizations, and obsessive creatives.

Perhaps it was inevitable that these two self-mythologizing figures would meet. Their paths intersected, not always at the same time, at many points throughout their respective travels.

Herzog once made a pilgrimage on foot from Munich to Paris, in the winter, believing the trek would save his friend German filmmaker Lotte Eisner’s life. He and Chatwin agreed: “The world reveals itself to those who travel on foot.”

When Chatwin was dying of AIDS, the story goes, Herzog paid him a final visit during which Chatwin entrusted him with his treasured, well-worn rucksack.

Thirty years later, Herzog revisits some of the far-flung places about which Chatwin wrote, and wondered, and dreamed.

The film isn’t meant, and doesn’t claim, to be biographical. “Chatwin was a writer like no other,” avers Herzog. “He would craft mythical tales into voyages of the mind. In this respect, we found out we were kindred spirits: he as a writer, I as a filmmaker. In this film here, I will follow a similar erratic quest for wild characters, strange dreamers and big ideas about the nature of human existence. These were the themes Chatwin was obsessed with.”

“Chapter One: The Skin of the Brontosaurus” refers to one of Chatwin’s most cherished childhood memories: the glass-fronted cabinet in his grandmother’s drawing room containing a piece of animal skin: thick and leathery with strands of coarse reddish hair. He was told that the skin came from a brontosaurus, an animal too large for Noah to load onto the Ark and that thus drowned in the Flood. This particular brontosaurus, the legend went, had come from Patagonia: “the country in South America, at the end of the world.”

“Never have I wanted anything the way I wanted that brontosaurus skin,” he later remembered. As an adult, he made a pilgrimage to a museum in La Plata, Argentina, where the rest of the skin was displayed and learned that the animal in question was actually a (now extinct) giant sloth. But in his memory a brontosaurus skin it forever remained.

As a boy, Chatwin would ride a bike from his boarding school in Marlborough to explore the rock formations of Stonehenge, in particular Silbury Hill, the largest Neolithic structure in the world. This was his pivot, his mythical place of origin.

His widow, Elizabeth Chatwin, weighs in from Llanthony Priory in the Black Hills of Wales. “This is a dreaming place. These hills … the landscape of his soul” to which he was always drawn back.

Chatwin had an interest in prehistory, “branches of evolution so ancient that speculation about them dissolves into the dream world.” He fell in love with extinct armadillos, a flying octopus.

Observes Chatwin biographer Nicholas Shakespeare: “He didn’t tell a half-truth; he told a truth-and-a-half. He embellished what was there to make it even truer.”

He searched for strangeness and was drawn to Herzog’s films for that reason. The two first crossed paths in the Australian outback, where Chatwin was researching for “The Songlines.” “The dreaming tracks. The Australian Aboriginals have this idea that the whole of the land is covered with song … totally incredible … it gives one insight into how language, song, thought, poetry came into being originally.”

Which came first, he wondered, the song or the landscape?

Herzog takes us as well to prehistoric caves in Tierra del Fuego, a shipwreck in Punta Arenas, and Navarino Island in Chile.

Chatwin’s charisma was legendary. Walking into a party, immediately he was surrounded by people of both sexes. He was a talker, interested in character, stories, jokes, adventures, mimicry. When asked about his philandering, his widow, deeply Catholic, replies: “I wouldn’t have dreamt of divorcing him. I mean there was no question about that.”

When Chatwin was dying, Herzog went to visit and showed him footage from “Herdsmen of the Sun,” his 1989 documentary about the Wodaabe tribesmen of Southern Sudan.

Chatwin’s legs were like spindles. His face was a death mask. “I’ve got to be on the road again. I’ve got to be on the road.”

According to Herzog, in his final years he made a pilgrimage to the monks of Mt. Athos and converted to the Greek Orthodox faith.

He died in January 1989, at the age of 49.

His ashes are buried on a promontory overlooking the Aegean Sea, next to a 12th-century church dedicated to St. Nicholas.

The last words he ever wrote: “Christ wore a seamless robe.”