I once gave a talk to a group of wealthy Catholic women. As is often the case in such situations, I was more or less the afternoon’s entertainment. The hat was passed and I ended up being given $90 to open my veins and tell the story of my conversion.

That was OK except that, in case you’ve never done such a thing yourself, you have to rev up (especially if you have a story like mine), steady your heart and steel your nerves for a day or two prior, pray like hell, and prepare to be drained to the bone.

Over by the refrigerator afterward, one of the women cornered me, narrowed her eyes, and hissed, “DID YOU VOTE FOR OBAMA?” In other words: “Speak, wretch! Are you or ARE YOU NOT the Antichrist?!”

We used to reserve such totalitarian behavior for the secret police: now we willingly surveil one another. No thought — from no matter how loving a heart; no matter how innocent — is exempt from being scrutinized, pounced upon, and assigned a malign and evil motive.

Now there must be public shaming, public demands for recantations, public “re-education,” public apologies.

No matter that we’re, for example, devoted, faithful fathers and husbands: Last year all males were expected to grovel for having been born male. No matter that we’re naturally appalled by the racial injustice against which every thinking person instinctively recoils: This year all Caucasians must grovel for having been born Caucausian.

The point is that both ends of the ideological spectrum are increasingly marked by bullying, “calling out,” and the imposition of a kind of martial law as to how we’re to speak, act, and think.

I don’t think this is a minor point: I think the phenomenon is very, very dangerous. Let’s not forget that another name for Satan is the Accuser. And I hope everyone’s read Arthur Koestler’s “Darkness at Noon.”

I’ve been thinking of another, somehow related remark I heard recently while watching Part 2 of a 1995 BFI series titled “A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies.”

Andre DeToth (1913–2002), the Hungarian-born film director (“Crime Wave,” “Hidden Fear”) who had lost the use of one eye, once said, “Life is a betrayal. And you know, sometimes you betray yourself too you know. Let’s have the guts to admit it. There isn’t anybody born here lately, who didn’t play dirty sometime somewhere in his life. So why do you hide it? Truth, honesty, that’s my key.”

In the Scorcese series clip DeToth, in eyepatch and elegant suit, goes on to observe in his cultured accent: “Violence in my opinion has become a definite point in a script. It has a dramaturgical reason to be there. You see, I don’t think people believe in the devil, with the horns and the forked tail. And therefore they don’t believe in punishment [long pensive drag on cigarette] … after they are dead.

“So my question was for me, what are people … in what belief people … or what are people feeling is better. And that is physical pain. Physical pain comes from violence. That I think is today the only fact which people really feel and thus it has become a definite part of life and naturally also of script.”

I think this touches on something very deep. To lose the sense of an afterlife is to say we have lost all belief in God. Culturally we have no sense of our own sin, or at least no outlet for it, so we’re reduced to blaming — and eventually tearing apart — one another. We have no altar before which to kneel, so we kneel before a flag or, equally if not more weirdly, one another.

On a related note, I’ve been pondering the phenomenon built deep into the human psyche: our urge to identify, then to kill, “the scapegoat,” a phenomenon to which the late philosopher René Girard devoted his career to exploring and describing.

Our scapegoat urge is in essence the original sin that started in the Garden of Eden. Adam blamed Eve, Eve blamed the snake, and we’ve been at it ever since.

It is at the root, for starters, of the blasphemy of racial discrimination and violence, as LA’s Archbishop José H. Gomez recently put it, directed against African Americans.

In our zeal to right the situation, though, I hope we don’t simply move the violence to another target: namely, one another.

At a religious conference I once attended, a black priest who served in the U.S. but had grown up in Africa uttered one of the truest and most chilling statements I have ever heard: “Something in us enjoys seeing other people suffer.”

He didn’t say it without hope; he said it as a way of drawing our attention to the human psyche, and to the forces of darkness that were arrayed against Christ. He didn’t mean we’re all sadists; he meant that as incarnate beings we’re hard-wired to put ourselves first, and that to overcome that urge requires help from a power greater than ourselves.

To fail to recognize this scapegoating mechanism in ourselves is a grave error. It leads for one thing to a kind of naiveté about the solution to the scourge of racial violence, and to violence of all kinds. In our naiveté, we think the way to wipe out sexual abuse against children is to wipe out the priesthood. In our naiveté, we think the solution to police brutality is to wipe out the police. In our naiveté, we think the way to wipe out human error is to wipe out history.

I, for one, betray myself and the people around me a hundred times a day. It’s no accident that the Mass begins with the penitential rite.

I don’t apologize for having been born Caucausian. I do, however, confess with all my heart to that darkness within me that, especially when cornered, will choose a scapegoat. I confess to that darkness within me that turns its face — to the poor, the rich, the prisoner, the person who on any given days is on the “wrong” side of the political fence, while subconsciously thinking, or more likely preferring not to “think” at all: Better you suffer than me.

And I confess to specific acts of malice or meanness, whether sins of commission or omission, that I have committed against specific human beings in the course of my day or life.

I confess and I’m willing to atone, to make amends for, not in some canned, pro forma way but by examining and where necessary, changing my life. Though the fruits of that change go out to the world, the examination of conscience is a matter between me and God, not for public consumption.

This is the only sane, sincerely convicted way to approach any sin against love.

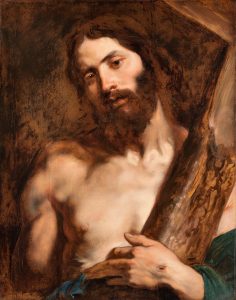

It’s before Christ, the ultimate scapegoat, that we kneel. It’s before Christ, the ultimate sacrifice, whose death reconciled us to the Father, ourselves and one another, that we prostrate ourselves in love.

Through Christ, ideology and accusations recede. Through Christ, we can marvel at one another as individual, complex human beings.

As many have pointed out these last weeks, not the least of the violence directed against people of color is the sense of being surveilled, avoided, shunned.

The police brutality is obscene. But the sense of being unfairly accused or suspected, of not feeling welcomed at the table — that’s what catches my heart.

That’s one change I truly long will come.