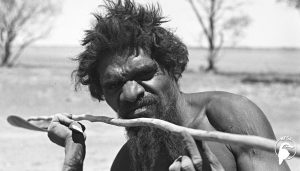

“Desert People” is an hourlong documentary shot in 1965 in the Gibson Desert of Australia’s Western Desert. Filmed in black-and-white and produced by the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, the film follows two families headed up, respectively, by Djagamara and Minma.

I happened upon the film on Kanopy (10 free monthly movies with your LA Public Library card!), watched a random sample, and ended up sitting through the whole thing, transfixed.

The Western Desert covers more than half a million square miles and is one of the most arid regions in Australia. At the time, possibly three or four family groups still remained, making their way as nomadic hunter-gatherers in this remote expanse of land.

These people had nothing, and I mean nothing! Not clothes, not shelter.

They had a fire stick, a long branch smoldering on one end that someone carried like a staff as they walked barefoot through the bush.

They sharpened other sticks with flints banged out on rocks, tracked lizards to their holes, speared the hapless creatures, then hung the reptiles like little trophies from their belts and saved them for dinner.

At night they tore off branches from trees and made a windbreak.

One of Djagamara’s seven kids was dispatched to a nearby waterhole, scooped water into a wooden trough with his hands, and carried the trough on his head back to camp.

Meanwhile, his three wives had gathered woolybutt grass and painstakingly sifted, culled, and ground the seed heads into meal, added water, and shaped the batter into cakes, which they roasted, along with the lizards and some stray mice, in hot ashes.

When Minma appeared in the second segment with an axe, it might as well have been an iPhone 12 Pro. Whoa dude! An axe! Where’d you get that?

Amazingly these desert dwellers appeared supple, healthy, and quietly joyful. Their hypnotic song-chant was so elementally “right” that it could have been sung by the land itself. I couldn’t get over how they could survive in such a harsh climate, with so little available water and food, and next to no resources.

But the shot that really got to me was of a little baby nursing. There he or she was, guzzling happily away, and the kid’s face was simply swarming: grotesque clusters of flies had settled in its nose, its ears, its mouth. Its little hand ineffectively tried swatting them away but already you could see the kid was resigned to the lifelong, no doubt constant, presence of these unbearably annoying, ruinous, pests.

I don’t know what kind of flies they were, and I don’t know if the flies bit, as tsetse flies do. Turns out there are more than 30,000 species of flies in Australia, including the blow fly, the bush fly, the cluster fly, the drain fly, and the fermentation fly.

I have my own little skin ailment that tends to act up in summer. Taking a walk the next day, scratching away, for a moment I felt sorry for myself. Then that poor infant’s face rose to mind, and I thought: “Why should I have it any better than that baby?”

Shall tribulation, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or danger, or sword separate us from the love of Christ, St. Paul asked (Romans 8:35).

What threatens to separate most of us from Christ is often the constant, unending annoyances of daily life.

In the First World, our swarms of tsetse flies are technological glitches. Our tsetse flies are dentist’s and doctor’s offices that text, call, and email six different times to confirm a simple appointment.

It’s emails asking us to review a can of shoe polish, a bottle of dish detergent, a frying pan. It’s having to unsubscribe from marketing and promotional lists, many of them Catholic, to which we never subscribed, or to which we specifically asked not to be subscribed, in the first place. It’s the printer that jams, runs out of toner, or wants, again, to print and scan an alignment page, always at the exact moment that you’re trying to meet a deadline.

It’s not being able to trust any news source, for any reason, because they are all so clearly trying to manipulate their readers into hatred and fear.

It’s being told your email address has been found on the dark web, that your book publisher has been hacked and your full name and Social Security number exposed, that you’ve been filmed watching porn online (I’m not kidding; this actually happened to me), and that you need to pay out $7,423 in blackmail money.

Like the besieged infant in the bush, we feebly protest, knowing that the forces arrayed against us are beyond our control. But take heart. None of us are alone.

Nailed to the cross, his mutilated hands feebly writhing, Christ couldn’t escape the human condition either.