For 15 years, photographer Emmet Gowin (b. 1941) intermittently traveled to the forests of Central and South America in order to learn about, live with, and capture the mysterious essence of moths.

“Mariposas Nocturnas: Moths of Central and South America (A Study in Beauty and Diversity)” (Princeton University Press, $39) is the result.

In the course of his decades-long career, Gowin has photographed his extended family, including his wife, Edith, his children, and his aging parents. In the 1980s, his focus shifted to aerial landscapes of America and Europe, with a special interest in environmental degradation stemming from the effects of irrigation, mining, and military testing.

At 75, he published his paean to moths.

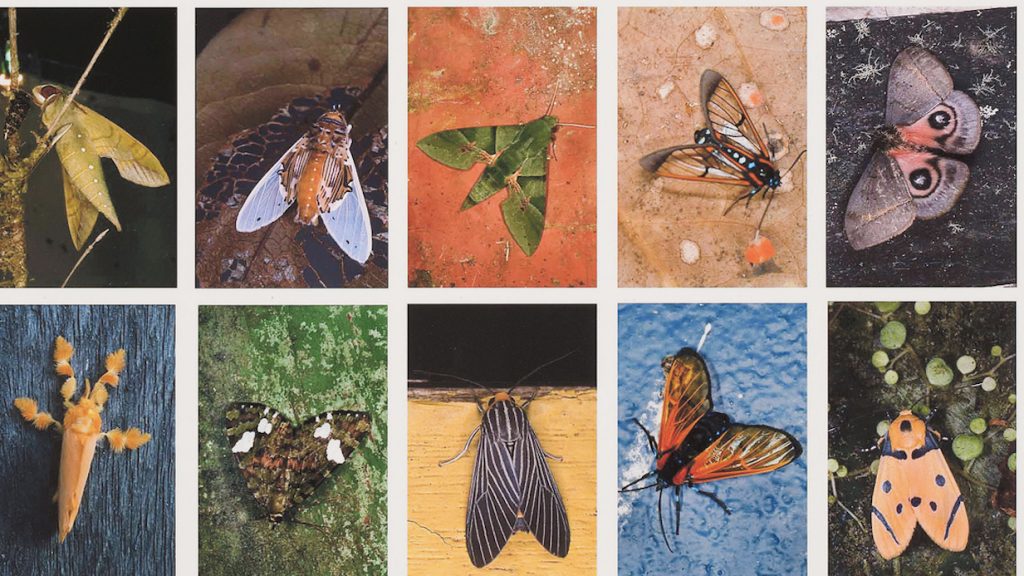

A hefty 11 inches by 14 inches, the book features 51 plates with 25 photos on each page as a reflective afterword by Gowin, and a foreword by American writer and conservationist Terry Tempest Williams.

“A mosaic of winged beings,” she describes the moths. “Robed priests and priestesses of darkness.” “Living oracles.”

“Within the indexes of ‘Mariposas Nocturnas,’ I can see whom we live among, with each moth’s accompanying name in Latin registering as a prayer: “Melese drucei,” “Parasa wellesca,” “Nemoria interlucens,” “Repnoa imparillis,” “Pryteria alboatra.” This is a liturgy of love that spans 160 million years of their evolution. Beauty is its own form of resistance.”

So breathtaking in fact are these creatures — with their almost unbelievable variety of design, color, shape, and poetry — that I had the book for a year before I could bring myself fully to take it in. I’d studied one plate and set the rest aside till I’d steeled myself.

As with a late Beethoven quartet, or a Cézanne still-life, the intensity of the beauty is almost too much to bear.

Like butterflies, moths undergo a metamorphosis — which only deepens the mystery. Gowin raised some species himself, from eggs he had watched the mother lay and that emerged the following spring.

Whether in Peru, Bolivia, Colombia, or Ecuador, almost all the moths were photographed while alive, at first “happily settled on a brightly painted wall under an electric lamp.” For the first five years, Gowin’s equipment consisted of one mercury vapor lamp, one black-light fluorescent tube, and a white collecting sheet.

Over time he learned which moths he could “coax to pose, which ones could be touched. I had to learn to work without offending their personalities.”

Later, he began collecting pieces of painted wood against which to photograph. Later still, he began bringing scanned and printed copies of some of his favorite works of art — Degas, Piero della Francesca, Matisse — and thereby stumbled upon the most fitting background of all. Contrasting one order of masterpiece with another unexpectedly honored them both.

Paging slowly through, every few seconds you sigh, sharply inhale, and exclaim: “Stop!” “Come on!” “Are you kidding me?” or “I want that one.”

Whatever you might think a moth looks like, think again. Moths can resemble torpedoes, swallowtail butterflies, praying mantises or bumblebees. They can be shaped like hearts, veined like leaves, or trompe-l’oeil scaled like fish. They can be furred, horned, or crested.

How can anyone say, after perusing these pictures, that God doesn’t have a sense of humor and a sense of fashion? We now know beyond doubt that he thoroughly approves of striped waistcoats, polka-dot ties, gauzy robin’s-egg-blue caftans, and the hats worn by women at the Royal Ascot.

Moths can be pomegranate, acid-green, jet black, ochre, verdigris, mother-of-pearl, rose, silver, or glittered with gold.

They can be patterned like a Japanese vase, a flamenco dancer’s skirt, a chip of Art Deco stained glass. They can have eyes, stripes, zigzags, scallops, and faces. They can look like a skyscraper, an inert scrap of lichen, or an M.C. Escher creation.

At last before this embarrassment of heretofore-unknown riches, you fall silent. You think about a Meister Eckhart quote: “God is like the suitor who, while hiding, coughs in order to give himself away.” While we’re complaining about the price of gas, he’s saying, “Hey, check out this ‘Omertica gerbilda!’ ” — with its apricot-and-ebony wings and a “tail” of electric blue.

Over time, Gowin says, “I have begun to see the moths as a living wonder; visually stunning, endlessly varied, mysterious, sometimes useful, sometimes destructive, hardworking, biologically intuitive, and nothing less than a miracle.”

Working with moths, he continues, “overwhelmed me with the feeling that I was being graced by a visit from an otherwise invisible world.”

The threat of environmental degradation — specifically deforestation — hangs over “Mariposas Nocturnas” like a shroud. As the forests go, so go the moths.

“Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth,” Jesus cautioned, “where moth and decay destroy, and thieves break in and steal. But store up treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor decay destroys, nor thieves break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there also will your heart be” (Matthew 6:19–21).

Only God could contrive to create a cosmos where the creatures who devour our earthly treasures are themselves — each one — a treasure beyond price.