Oscar Wilde famously said that he could resist everything but temptation.

He was a funny guy — and that’s a funny line. But he wasn’t a happy guy, and his one-liners are a window into his unhappy life. He pursued pleasure, maybe in the hope that he could fashion some lasting joy out of sensual delights and amusements. It didn’t work for him — and it doesn’t really work in the lives of any addicts.

Pleasures are not joys. When we seek them out, they can become idols. They can come to preoccupy us as only God should — motivating our actions and conversations. Our friends and family notice, even if we don’t, that our indulgence makes us obnoxious and boring. Our pleasures make us predictable. People sense that they’re not very important to us, at least in relation to whatever tempts us: our next drink, our next meal, our next shopping spree, or whatever our particular demon may be.

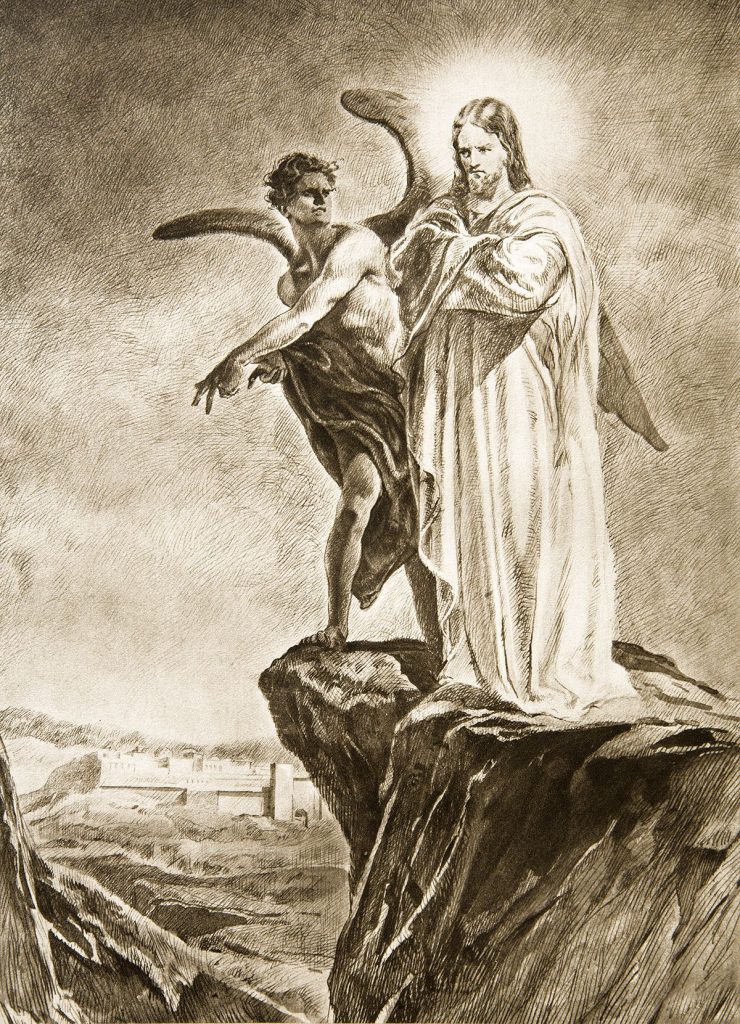

Jesus himself faced temptations and overcame them, one by one.

We know about Jesus’ ordeal in the desert only because Jesus himself chose to reveal it. How else could the evangelists have found out? The Lord was alone when the devil closed in.

But he judged the event important enough to share with his disciples. It’s important for many reasons, but not least because it underscores the power of temptation — and also the power we have to overcome it. We have the power because Jesus has the power, as we can see, and he freely shares his life and strength with us.

Jesus was fasting when the devil came after him. By fasting — and, later, by telling his disciples the story — he set the program for our own Lenten practices. We fast because Jesus did, because John the Baptist did. And so did the Apostles, and Moses, Elijah and David. Fasting isn’t the most important part of biblical religion, but it is certainly an important and essential part.

Jesus shows us why. If we do it right — if we match it up with a life of prayer and almsgiving — it frees us from our impulses, our obsessions and our major distractions. By giving up things that are good in themselves (like candy, meat or craft beer), we strengthen ourselves to overcome things that are genuinely sinful.

Because, make no mistake, the devil may start by tempting us with good things or neutral things, but he really wants to ramp us up to the hard stuff. He wants us to be proud, gluttonous, angry, lustful, envious, greedy and lazy.

We will be tempted when we show the slightest movement toward a closer relationship with God. The Good Book tells us: “My child, when you come to serve the Lord, prepare yourself for trials.”

Jesus knew this, and that’s why he built “Lead us not into temptation” into the most basic prayer he taught us. That’s why he advised his apostles: “Watch and pray that you may not enter into temptation.” He even warned us that it’s “in time of temptation” that many believers “fall away.”

Temptations will come, Jesus said. They’re inevitable. But we don’t need to give in. St. Paul commented: “No trial has come to you, but what is human. God is faithful and will not let you be tried beyond your strength; but with the trial he will also provide a way out, so that you may be able to bear it.” The Greek word for trial means temptation, too. So St. Paul recognizes that temptation is part of the human package since Adam and Eve.

But we don’t need to sin as Adam and Eve did. We don’t need to be unhappy as Oscar Wilde was, even with all his cleverness.

We can prevail as Jesus did. St. Paul goes on, in that chapter from 1 Corinthians, to talk about our “way out.” It’s the Eucharist, the body and blood, soul and divinity of Jesus — the very means by which he overcame the devil.

Through Lent we’re fasting with Jesus, turning toward Jesus, imitating him and growing every day into a closer communion with him. With his strength we can resist everything. Period.