“Immersion journalist” Katherine Boo is a staff writer for The New Yorker. Her series about group homes for the intellectually disabled won the Washington Post the 2000 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service. She has been awarded a MacArthur “genius” grant.

She has also suffered from rheumatoid arthritis since childhood. Her health is frail. Still, she felt moved to spend four years quietly walking among, standing besde, and observing the people of Annawadi, a Mumbai slum hard by an international airport and a sewage lake.

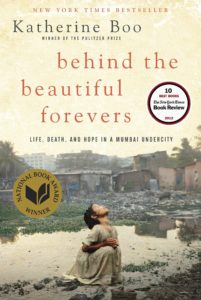

Her 2012 book, “Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity” (Random House, $23.02), won the National Book Award, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and many others. A decade after publication, it’s still the best account I know of an author evincing true solidarity with the poor, love for our neighbor, and “activism” without a scintilla of politics or ideology.

New York magazine noted that the book is “reported like Watergate, written like ‘Great Expectations,’ and handily the best international nonfiction in years.” It’s been called “a tour de force of social justice reportage,” “a literary masterpiece,” and an “interview-based narrative in which the interviewer never appears.”

It begins like this:

“Midnight was closing in, the one-legged woman was grievously burned, and the Mumbai police were coming for Abdul and his father. In a slum hut by the international airport, Abdul’s parents came to a decision with the uncharacteristic economy of words. The father, a sick man, would wait inside the trash-strewn, tin-floored shack where the family of 11 resided. He’d go quietly when arrested. Abdul, the household earner, was the one who had to flee.”

Boo is tender without sentimentality. She is realistic without despair. This is how the slum-dwellers made a living:

“Every morning, thousands of waste-pickers fanned out across the airport area in search of vendible excess — a few pounds of the eight thousand tons of garbage that Mumbai was extruding daily. These scavengers darted after crumpled cigarette packs tossed from cars with tinted windows. They dredged sewers and raided dumpsters for empty bottles of water and beer. Each evening, they returned down the slum road with gunny sacks of garbage on their backs, like a procession of broken-toothed, profit-minded Santas.”

Out of those thousands of waste-pickers, Boo picks one, a smart, hard-working, and almost comically resourceful boy named Abdul around whom the book’s central drama unfolds.

“When I settle into a place, listening and watching,” says Boo, “I don’t try to fool myself that the stories of the individuals are themselves arguments. I just believe that better arguments, maybe even better policies, get formulated when we know more about ordinary lives.”

As Abdul makes his rounds, scavenging, bargaining, weighing scrap metal, he ponders the morality of slum life and the mystery of existence:

“Water and ice were made from the same thing. He thought most people were made of the same thing, too. He himself was probably little different, constitutionally, from the cynical, corrupt people around him — the police officers and the special executive officer and the morgue doctor who fixed Kalu’s death. If he has to sort all humanity by this material essence, he thought he would probably end up with a single gigantic pile. But here was the interesting thing. Ice was distinct from — and in his view, better than — what he was made of.”

“He wanted to be better than he was made of. In Mumbai’s dirty water, he wanted to be ice.”

From reviewer Amrit Dhillon: “The most astonishing feature of this Promethean work of reporting by the American journalist Katherine Boo is the sound of poor Indian voices that comes through every page. Their thoughts about their mothers and fathers, homes, neighbours, work, children and dreams are not often heard in a country where the poor are seen everywhere but are usually silent.”

“In the first few weeks, Boo is treated as a circus freak by the slum-dwellers who, assuming she has lost her way to a nearby hotel, shout ‘Hyatt!’ or ‘Intercontinental!’ When she is still around, months later, recording conversations, conduct and incidents, she finally becomes a part not of the furniture (there is no furniture in these hovels) but of the landscape: the piles of rubbish, the excrement-caked pigs and goats, the alcoholics and the sewage lake.”

The Guardian asked, “Was she never scared of the rats, whose bites marked the children’s bodies and sometimes exploded in worms?” Boo replied, “I’m not squeamish. Tuberculosis was a concern: there were many people I spent time with whose stories were that they got sicker and sicker and then they died. But if you’re really curious, you don’t dwell on it that much.”

Boo is firmly enshrined in my personal communion of saints, a subset of which is “Writers Who Are Catholic Without Being Catholic.” Would that more of us wrote with Boo’s curiosity, excellence, intelligence, willingness to suffer, and heart.

“We try so many things,” as one Annawadi girl put it, “but the world doesn’t move in our favor.”

In 2021, Boo was elected as co-chair of the Pulitzer Prize board. She is currently working on her next book, “an exploration of social mobility in low-income families that draws on years of intimate reporting from African American neighborhoods in Washington, D.C.”