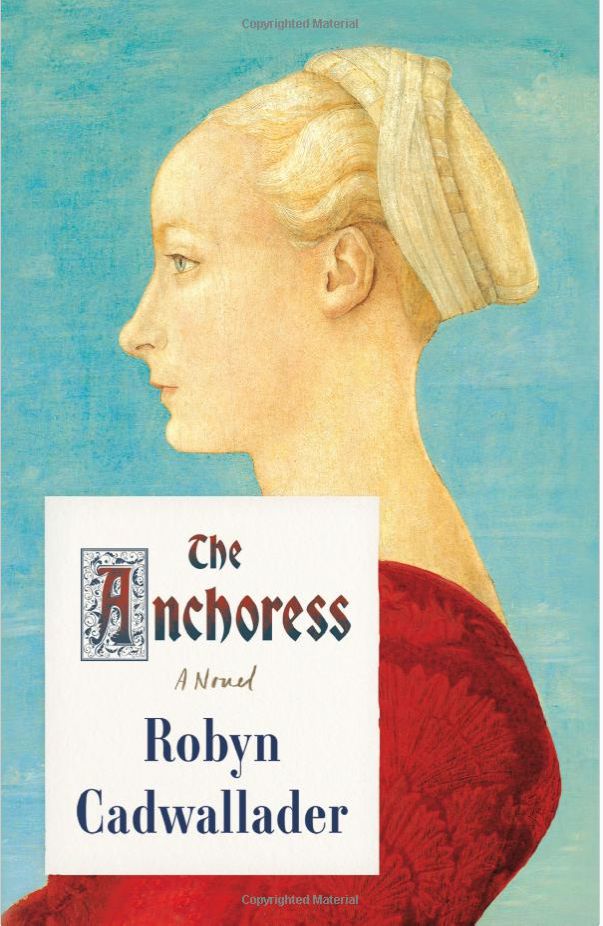

A recent book by Robyn Cadwallander, “The Anchoress,” tells the story of a young woman, Sarah, who chooses to shut herself off from the world and lives as an anchoress (like Julian of Norwich).

It’s not an easy life and she soon finds herself struggling with her choice. Her confessor is a young, inexperienced monk named Father Ranaulf. Their relationship isn’t easy. Ranaulf is a shy man of few words, and so Sarah is often frustrated with him; wanting him to say more, to be more empathic and simply to be more present to her.

They often argue, or, at least, Sarah tries to coax more words and sympathy out of Ranaulf. But whenever she does this he cuts short the visit and leaves.

One day, after a particularly frustrating meeting that leaves Ranaulf tongue-tied and Sarah in hot anger, Ranaulf is just about to close the shutter-window between them and leave, his normal response to tension, when something inside him stops him. He knows that he must offer Sarah something, but he has no words.

And so, having nothing to say but feeling obliged to not leave, he simply sits there in silence. Paradoxically, his mute helplessness achieves something that his words don’t — a breakthrough. Sarah, for the first time, feels his concern and sympathy and he, for his part, finally feels present to her.

Here’s how Cadwallander describes the scene:

“He took a deep breath and let it out slowly. There was no more he could say, but he would not leave her alone with such bitterness. And so he remained on his stool, feeling the emptiness of the room around him, the failure of his learning, the words he had stacked up in his mind, page upon page, shelf upon shelf. He could not speak, but he could stay; he would do that. He began to silently pray, but did not know how to go on, what to ask for. He gave up, his breath slowed.

“The silence began as a small and frightened thing, perched on the ledge of his window, but as Ranaulf sat in stillness, it grew, very slowly, and filled up the parlor, wrapped itself around his neck and warmed his back, curled under his knees and around his feet, floated along the walls, tucked into the corners, nestled in the crevices of stone. … The silence slipped through the gaps under the curtain and into the cell beyond. A velvet thing, it seemed. It swelled and settled, gathering every space into itself. He did not stir; he lost all sense of time. All he knew was the woman but an arm’s length away in the dark, breathing. That was enough.

“When the candle in the parlor guttered, he stirred, looked into the darkness. ‘God be with you, Sarah.’ ‘And with you, Father.’ Her voice was lighter, more familiar.”

There’s a language beyond words. Silence creates the space for it. Sometimes when we feel powerless to speak words that are meaningful, when we have to back off into unknowing and helplessness, but remain in the situation, silence creates the space that’s needed for a deeper happening to occur.

But often, initially, that silence is uneasy. It begins “as a small frightened thing” and only slowly grows into the kind of warmth that dissolves tension.

There are many times when we have no helpful words to speak. We’ve all had the experience of standing by the bedside of someone who is dying, of being at a funeral or wake, of sitting across from someone who is dealing with a broken heart, or of reaching a stalemate in trying to talk through a tension in a relationship, and finding ourselves tongue-tied, with no words to offer, finally reduced to silence, knowing that anything we say might aggravate the pain.

In that helplessness, muted by circumstance, we learn something: We don’t need to say anything; we only need to be there. Our silent, helpless presence is what’s needed.

And I must admit that this is not something I’ve learned easily, have a natural aptitude for, or in fact do most times when I should. No matter the situation, I invariably feel the need to try to say something useful, something helpful that will resolve the tension. But I’m learning, both to let helplessness speak and how powerfully it can speak.

I remember once, as a young priest, full of seminary learning and anxious to share that learning, sitting across from someone whose heart had just been broken, searching through answers and insights in my head, coming up empty, and finally confessing, by way of apology, my helplessness to the person across from me.

Her response surprised me and taught me something I’d didn’t know before. She said simply: “Your helplessness is the most precious gift you could share with me right now. Thanks for that.” Nobody expects you to have a magic wand to cure their troubles.

Sometimes silence does become a velvet thing that swells and settles, gathering every space into itself.