On a recent trip to the Chicago area, I was able to visit the National Shrine of St. Maximilian Kolbe in Libertyville, Illinois. The shrine comprises the Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament Chapel, a Rosary Garden, and a Conventual Franciscan Friary.

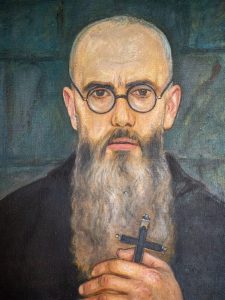

St. Kolbe (1894-1941) is the Polish priest who offered to take the place of a fellow prisoner condemned to die in the starvation bunker at Auschwitz.

The chapel, open to the public 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, is dedicated to Perpetual Adoration, and has been since 1928 (the original temporary chapel moved to the current site in 1932).

Marytown, as the site is called, serves a broad apostolate — locally, nationally, and internationally — through Eucharistic Adoration, a prison ministry, daily Masses, weekday confessions, and a retreat program.

The side Passion/Kolbe Chapel contains first-class relics. Downstairs is a Holocaust exhibit with timelines, photos, and a mockup of the starvation bunker. The whole shrine is clothed with the “odor of sanctity.” I’m not sure I’ve ever been in a place that felt more holy.

Patricia Treece’s “A Man for Others” (Marytown Press, $34.36) tells more of the saint’s backstory.

From childhood, he had a deep devotion to Mary, who in prayer had appeared to him holding two crowns — one white, signifying purity; the other red, signifying martyrdom — and asked if he would like them. “Yes,” he replied, whereupon Mary looked at him tenderly and disappeared.

He went on to become a Conventual Franciscan friar and a priest, settling at a monastery near Warsaw called Niepokalanów. Here, he established a community and a printing press that turned out pamphlets, books, a daily newspaper and a monthly magazine that had over a million subscribers.

In 1917, he founded the Militia Immaculata (Army of Mary), a worldwide evangelization movement. He also began to exhibit signs of the TB that would plague him for the rest of his life.

Starting in 1930, he served several years in Japan as a missionary but ill health forced him to return to Poland. During the German occupation that marked the beginning of World War II, he remained at Niepokalanów — which at 650 members was then the largest religious house in Europe — and continued to publish, including material that was critical of the Nazi regime. He was arrested in February 1941, and eventually transported to the concentration camp at Auschwitz.

One fascinating phenomenon underscored by Treece: Father Kolbe was a smallish man, far from robust, who continued to suffer from TB. Yet at Auschwitz he seemed to have been graced with a kind of supernatural strength. How was it that a sickly priest — priests were singled out for especially savage treatment by the guards — could endure the cold, the hard labor, the severe beatings, the starvation rations?

It was as if his destiny — his martyrdom — had been marked out in advance.

“Father Kolbe never asked for anything and he never complained,” writes Treece.

“Those eyes of his were always strangely penetrating. The SS men couldn’t stand his glance, and used to yell at him, ‘Schau auf die Erde, nicht auf uns!’ (‘Look at the ground, not at us.’)”

At the end of July 1941, a prisoner escaped from Auschwitz. The Nazis called for 10 others to die in his place. A sleek, well-fed commandant ordered the emaciated, lice-ridden prisoners to stand in rows and sauntered casually through, randomly pointing to those who were to starve to death.

When he pointed to inmate Francis Gajowniczek, the man broke down, wailing, “My wife! My children!” Whereupon, in an unthinkable breach of protocol, Father Kolbe stepped out of line and asked to take the man’s place.

Another inexplicable occurrence: Why did this hardened SS man not snarl, “Fine, then you can both die”? Instead, he barked his permission and the 10 were thrown into the bunker, naked. After two weeks only four prisoners were still alive; Father Kolbe, still conscious, among them. At last a guard came and injected the men with carbolic acid.

Father Kolbe was murdered on Aug. 14, the vigil of the feast of the Assumption, and cremated. Years before, he had remarked, “I would like to be ground to dust for the Immaculate Virgin and have this dust be blown away by the wind all over the world.”

A remarkable postscript: Rudolf Hoess, the commandant who ordered the 10 to die, had also introduced the pesticide Zyklon B into the gas chambers, and was thus responsible for upwards of 2 1/2 million other deaths.

At the end of the war he was arrested and, days before dying, wrote to the state prosecutor:

“In the solitude of my prison cell, I have come to the bitter recognition that I have sinned gravely against humanity … May the Lord God forgive one day what I have done.”

Hoess converted on his deathbed, confessed to a priest, and returned to the Catholic faith of his youth before being hanged.

In the Foreword to “A Man for Others,” Father Patrick Greenough opines that St. Kolbe laid down his life not just for Francis Gajowniczek, but for the other nine who were condemned — and for Hoess as well.

Or as St. Kolbe had written to his mother back in his youth, “Pray that I will love without any limits.”