Back in the 1990s, Sister Wendy Beckett (1930-2018), a contemplative nun and consecrated virgin, delighted audiences worldwide with her lively BBC documentaries on the history of art.

Born in Johannesburg, she joined a teaching order in 1946, and then earned a degree in English Literature at Oxford, graduating with highest honors.

After teaching in South Africa from 1954 to 1970, she suffered a physical and emotional collapse and was granted permission to return to England.

There she stayed for decades on the property of the Carmelite Monastery in Quidenham, Norfolk, first in a caravan; later in a small room. Her true vocation was to take place in silence and solitude. She prayed for seven hours a day.

With permission, she began to study art history. Her first television appearance was in a 1991 BBC short. In full habit, and with her trademark owlish glasses, overbite, and slight speech impediment such that her r’s became w’s, she became a sensation.

She went on to host her own shows — “Sister Wendy’s Odyssey”; “Sister Wendy’s Grand Tour” — and to write more than 30 books. Hands clasped in joy, face framed by a wimple, she could hold forth with equal enthusiasm on Andy Warhol’s “Marilyn Diptych” and a Rembrandt self-portrait.

The TV run faded out, she returned to her cloister, and twenty years passed. Enter Robert Ellsberg, publisher of Orbis Books, who in the spring of 2016 entered into an epistolary friendship with Sister Wendy.

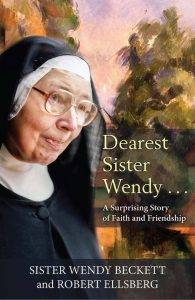

“Dearest Sister Wendy: A Surprising Story of Faith and Friendship” (Orbis Books, $28) is the result — and it’s a fascinating read.

We get a bird’s-eye view of the life of a contemplative who crammed her tiny room with postcards and icons, barely slept or ate, and rose after an afternoon rest at 8 p.m. to begin her daily round of prayer,

Still, over and over again, she insists she has nothing to say. Surely you do, counters Ellsberg. How about if I ask you questions? OK, replies Sister Wendy, but I guarantee you’ll be bored. On it goes for 2 ½ years (the book ends with Sister Wendy’s death), Ellsberg cajoling Sister Wendy against her better judgment, for the most part giving in.

We’re grateful she does. Sister Wendy is utterly delightful: original, surprising, diplomatic, and profoundly loving but with strong opinions. She cannot share Ellsberg’s near hero-worship of Father Thomas Merton, for example. Though she’s read everything Merton’s ever written with avid interest, she’s appalled that he “describes the most extraordinary breaches of the rule without the slightest contrition or even awareness that he promised to live otherwise.”

Ellsberg sees this as admirable, the sign of a free spirit whose mission was to show the world a new way to be a monastic. Sister Wendy, whose life of faith means denying herself everything that “isn’t necessary or would intrude” — including, for example, music — politely but firmly disagrees. Merton was a genius with a heart longing for God but no saint, and she knows no contemplative who finds him remotely helpful.

To their mutual credit, they both accept their differences and warmly search for the similarities. Sister confides that she’s always hated her name and cheerfully admits to her protruding teeth. Ellsberg chides Sister Wendy for her over-the-top (to him) asceticism; she chides him for his overwork.

On one level, in fact, the book can be read as a dialogue about the active versus the contemplative life.

The son of a “great man,” as Ellsberg puts it (his father was the Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg), he was also deeply marked by the time he spent as a youth with Servant of God Dorothy Day as managing editor of the Catholic Worker newspaper, and later, during the last five years of her life.

Sister Wendy also deeply admires Day. Nonetheless, she seems to intuit that beneath all Ellsberg’s terrific writing on the saints, incessant travel, and friendships with “important” people, he longs to be seen, held, loved for himself alone.

Another way “in which you and I are very different,” she confides almost two years into their correspondence, “is that your wonderful father has brought you up to value social justice very highly…I don’t want to shock or alienate you, dearest Robert, but I cannot take much interest in this topic so dear to you and Pope Francis and to all serious Christians. It all seems to me so obvious. Of course war is wrong; of course there should be social justice; of course we should love and revere one another…But I feel that’s a sort of a given for me. I don’t feel any call to fight for it or even to talk about it.”

That’s what seven hours of prayer, every day for 70 or 80 years, will get you.

One of her last nuggets of wisdom, in fact, echoes the Dorothy Day maxim: “I only love God as much as I love the person I love the least.”

For those who disliked the president at the time, she said: “Perhaps you should put Mr. Trump on the altar and sacrifice all your reactions to him. Where does it get you? He needs love as does everybody and he needs reverence as does everybody. God despises nothing ‘that He has made.’ ”