More than 27,000 individuals have been recognized as “Righteous Among the Nations” at Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial established in 1953 in Jerusalem. The criteria to receive the honor includes being a non-Jewish person who risked life, liberty, or safety to rescue a Jew from the threat of death or deportation; there must be eyewitness testimony or unequivocal evidence of their actions; and they must not have received any monetary or other rewards.

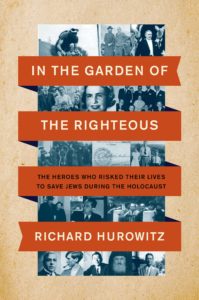

The number might seem large. But in his recent book, “In the Garden of the Righteous: The Heroes Who Risked Their Lives to Save Jews During the Holocaust” (Harper, $28.99), author Richard Hurowitz points out that 27,000 people represent one-half of one-hundredth of 1% of the European population during World War II, or about 1 in 20,000.

Not all rescuers were known, of course. Many were killed by the Nazis; others never spoke of their work. Nonetheless, “they were, indeed, truly “rara avis,” the rarest of birds,” Hurowitz said.

Hurowitz chose to bypass such already well-known rescuers as Raoul Wallenberg, Oskar Schindler, and Ángel Sanz-Briz, the Spanish “Angel of Budapest.”

Instead, he selected 10 stories that offer a wide spectrum of demographics, beliefs, geographies, and nationalities — stories that especially spoke to him.

André Trocmé (1901-1971), for example, was a Protestant pastor during World War II who mobilized his entire village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon in southeastern France to shelter and aid Jews fleeing the Nazis and their French collaborators. It was their Christian obligation, he insisted.

In his diplomatic capacity as Japanese vice-consul, Chiune (Sempo) Sugihara (1900-1986), by most accounts, helped 6,000 or more Jews escape the Holocaust. During the period from July 31 to Aug. 28, 1940 — with their careers, freedom, and the future of their four sons at stake — Sugihara and his wife issued handwritten visas for hours each day, including for those with incomplete paperwork, no money, and some with no travel documents at all.

“You want to know about my motivation, don’t you?” he once asked an interviewer. “Well. It is the kind of sentiments anyone would have when he actually sees refugees face-to-face, begging with tears in their eyes.

“I do it just because I have pity on the people. They want to get out so I let them have the visas.”

The courage of these figures is astounding. I read their stories praying on the one hand, “Lord, don’t put me to the test,” and on the other, “Lord, let me but touch the hem of one of their garments.”

Irena Sendler (1910-2008), a Polish Catholic social worker, is credited with saving more than 2,500 Jewish children by smuggling them from the Warsaw Ghetto and establishing them in individual and group homes across the country.

When World War II began, Sendler was a 29-year-old social worker and Jews constituted a third of Warsaw’s population: hounded, beaten, starved, and herded into the ghetto.

“In 1939 when the Germans invaded, Poland was drowning in a sea of blood,” Sendler said. “And it was the Jewish children who suffered the most.”

Aiding a Jew was subject to the death penalty, yet an extraordinary resistance movement formed, consisting of Polish Democrats and other Catholic activists, to carry out the perilous work of providing food, shelter, and forged documents. The Council for Aid to Jews, known by its code name, Zegota, selected Sendler as the head of its Children’s Bureau.

When the Nazis began transporting Jews to death camps, many parents made the agonizing choice to leave their children behind. Sendler finagled new identities for these young boys and girls, forged documents, and arranged for them to be adopted by non-Jewish families.

She kept an encrypted ledger of the children’s real names, Polish aliases, and addresses, partly so they could be returned to the Jewish community after the war ended, and partly because she believed that every child deserves a name.

She was arrested by the Gestapo on Oct. 20, 1943, imprisoned, and over a period of three months, tortured. Her interrogators truncheoned and whipped her feet and legs, crippling her for life, but she never divulged the names of either her collaborators or the hidden children. She was saved from execution when a friend bribed a guard.

By the end of the war, 90% of the children she had saved were dead. Trying to locate the parents of the survivors — most of whom had also died — was another herculean task.

She was named “Righteous Among the Nations” in 1965 and was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007. She died at age 98 accompanied, among others, by one of those she had saved.

In her autobiography she wrote, “This constant emphasis on how extraordinary our work was — it is uncomfortable. A Jew, a Frenchman, a German, they are, after all, the same people, like us — that was the only thought in our minds. That which we did came from a need in our hearts.”