A Romanian Jew who became a French intellectual, Benjamin Fondane was a man of many parts.

A poet, a philosopher, a cineaste with connections to the French avant-garde, he was a citizen of the world involved in the cultural life of three countries: Romania, France, and Argentina, where he lived briefly. He was also a friend of leading cultural figures in France, including the formidable Catholic thinkers Jacques Maritain and his wife, Raissa.

The man lived in the whirlwind of the chaotic first half of the 20th century, always as an outsider to the many movements he encountered. He died the quintessential outsider — a victim of the Nazi genocide, killed at Auschwitz just days before the Russians liberated the camp.

Fondane was, besides, a prophet. In philosophy, he was close to a Russian existentialist and religious thinker, Lev Shestov.

Maritain, who tried unsuccessfully to save him from the Holocaust, described him as “a disciple of Shestov, but one inhabited by the Gospel.” Fondane, the Jew, said that “the powerlessness of Christ” was “stronger than all the powers of the world.”

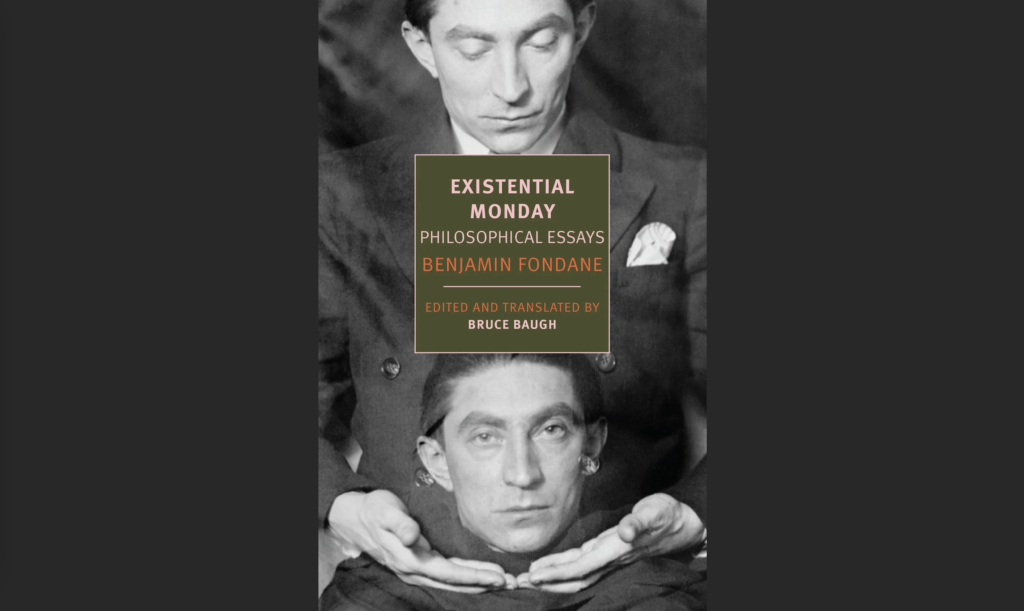

I only recently encountered Fondane in a book of his philosophical writings entitled “Existential Monday: Philosophical Essays” (New York Review Books, $16).

Eclectic is a word that would have to be invented for Fondane had it never existed. He told Maritain that he and his mentor Shestov were attempting a thought rooted in Judaism but indebted to the Christianity of Kierkegaard, Martin Luther, and Tertullian. Besides those heretics, throw Pascal, Kafka, Baudelaire, and Rimbaud into the mix and you have a sense of the reach of Fondane’s culture.

It is a testament to both Maritain and Fondane that they could be friends despite such different ideas. I think what united them was a deep skepticism of modern culture, which, since the Enlightenment, has attempted to find meaning for mankind without resorting to the God of revelation.

In words that are as true today as they were in his time, Fondane said “we think that we are sheltered from the convulsions of a culture that risks burying us in the debris of its collapse.”

Kant and Hegel, Heidegger and Sartre, even Camus seemed to Fondane to be part of a conspiracy to limit humanity with a bleak future based solely on reason, defined in a way that demanded a transcendence without a transcendent, and condemned the individual to a stoic meaninglessness.

“Human nature,” he wrote, “has not withstood the inhuman Tower of Babel which we have erected and which we have called civilization.”

Fondane saw the “Nazi Caliban” threatening Europe not as an aberration of the progress of the Enlightenment but as its final fruit. Civilization without God ended up in the cul-de-sac of the concentration camps.

He called for a “far-sighted humanism based on human wretchedness.” The “overestimation of reason,” as he saw it, resulted in putting “all of science’s trump cards in the hands of” the enemies of humanity.

This has application today: Nazi science presaged the horrors of all the Frankenstein experiments today accepted by modern researchers, for instance, the frozen embryos and fetal flesh used by Big Pharma in its insatiable thirst for profits. The Nazis were the advance guard for abortion, certainly. Planned Parenthood, recognize your ancestor!

Fondane called for an “irresignation” with regard to what was called “humanism” (really, secular humanism). He said the modern proponents of humanism “staked too much on the separate and divine intellect [of human beings] and neglected more than it ought to have real man, whom we had treated as an angel only to finally reduce him to a level lower than the beasts.”

This “irresignation,” a word he coined, was not the same as unresignation. More than a failure to be resigned to the meaninglessness of life, it was a refusal to be resigned to a world that was not open to God.

“As long as we hope to be victorious by our own strength and the strength of the Idea, as long as we have not yet lost everything and lost it irremediably, the relationship between man and God has still not been opened,” he asserted.

Fondane not only preached irresignation, he also lived it.

Although a naturalized French citizen married to a Gentile, the poet was arrested several times by the Germans who occupied Paris. Once captured while serving in the French military, he escaped, another time he was released. But the third time he was detained, taken to the infamous Drancy concentration camp where the French Catholic poet and convert Max Jacob died.

Fondane’s sister was arrested with him. When it came about that his friends had negotiated his release again, he refused to go without his sister. He could not be “resigned” to saving himself while allowing his sister to be taken. They both died in Auschwitz. That is irresignation incarnate, and merits as much admiration as his intellectual stance.

In the years since his death, his work in literature and philosophy has been recognized in France. In English-speaking countries, he is far less known but that seems to be changing.

Fondane has a lesson for people of faith.

In a poem about his military service fighting the Nazi onslaught, “I myself carried a rifle,” he talked about his connection with salvation history. “I crossed the Red Sea on foot,” he said and then remarked about his understanding that without God we are nothing. “Did I think that I could halt History with a rifle but without Him?”

There is a lovely Catholic epilogue to his story. The Maritains entered his history after death, also, especially by their friendship with Fondane’s wife, Genevieve Tissier-Fondane. They secured employment for her after the end of World War II and coaxed her back to the practice of the Catholic faith. She eventually became a sister of the Congregation of Notre-Dame de Sion, a congregation that had as its hallmark the evangelization of the Jewish people.