If you’ve ever visited a Holocaust museum, you probably felt the oppressive burden of encountering so much evil and sin. It leaves you wondering how such darkness can be expiated, how humans can wreak such horror on other human beings.

And yet they did. And do.

I had this experience recently during a tour of civil-rights sites in Montgomery and Selma, Alabama. If we have ever questioned how the Germans could have unleashed such horror on Jews, homosexuals, and others, then we should ask the same question of our own country when the racial sins of past and present are graphically presented to us.

Montgomery, the capital of Alabama, once called itself the “cradle of the Confederacy.” It was one of the nation’s largest slave markets before the Civil War. By 1860, Montgomery had 400,000 slaves. After the war and Reconstruction, its government, like much of the nation, instituted Jim Crow laws that trapped Black Americans in a cycle of impoverished servitude so effectively that the Nazis studied the system, aspiring to do the same for the Jews. But Montgomery is also where Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white person. It was where Martin Luther King pastored the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church and where his home was bombed. It is where the modern civil rights movement began.

It is in Montgomery where there is today a concerted effort to get America to face its past with courage and humility.

The architect of this encounter with our past is Bryan Stevenson. A Black American and Harvard Law School grad made famous by the book “Just Mercy” (One World, $20), and the movie of the same name, Stevenson might be more rightfully compared to an Old Testament prophet given the mission to convince America to own up to her history to more effectively respond with justice to the challenges of the present.

Since he founded the Equal Justice Initiative in 1989, providing much overdue legal counsel for Black Americans on death row or in lifelong incarceration, Stevenson has been convinced that until America is clear-eyed in facing its past injustices, until it faces the real horrors it allowed, it cannot be truly healed in the present. This is not easy work.

“We have to get comfortable with doing the uncomfortable,” Stevenson has said. “Justice never comes when you only do what is comfortable and convenient. Change never comes. Oppression never ends. Equality never prevails.”

In the bosom of the Confederacy, Stevenson has given us the tools to face our past and to understand our present more clearly.

Montgomery’s Legacy Museum is chattel slavery’s equivalent of a holocaust museum. One hears the voices of mothers whose children were taken from them and sold. One feels the lash and winces at the cruelty not only of the centuries of slavery, but the post-Reconstruction era that was slavery’s next phase. The Jim Crow laws, the terror lynchings, the casual brutality that extends even today in the mass incarceration that virtually guarantees one out of every three Black boys born will end up in prison.

There is also Montgomery’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which dramatically memorializes every county in the United States where lynchings have been proven to have occurred from 1877 to 1950. So far, the lynchings of 6,500 Black men and women have been documented.

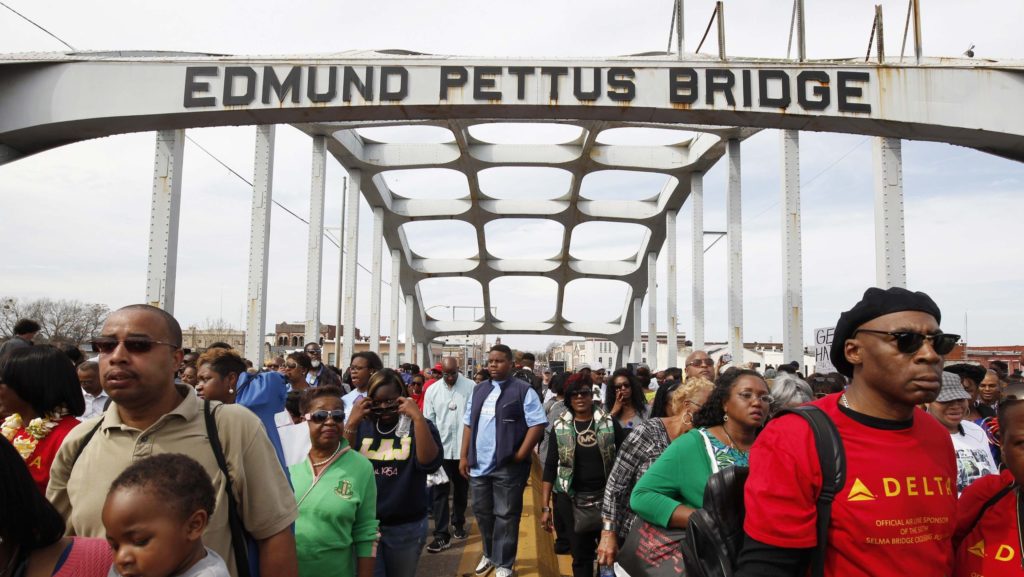

I was privileged to have participated in a Civil Rights Movement pilgrimage of sorts recently, sponsored by the Catholic Mobilizing Network and the Congregation of the St. Joseph Ministries. I crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, which was the pivotal scene of the 1965 voting rights march to Montgomery. I also went to the Rosa Parks Museum and the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park.

Why do this? Why would anyone put himself through something so disturbing? I say we “have to get comfortable with doing the uncomfortable.”

Recent efforts to censor government websites and remove references to institutional racism and the heroes who struggled against it condemn us only to more ignorance and a delayed reckoning. It risks new horrors against despised minorities. It leaves the darkness in our human hearts unexposed to the light.

The U.S. Catholic bishops explain why we must face up to our past in their 2018 pastoral letter against racism called “Open Wide Our Hearts”: “The evil of racism festers in part because, as a nation, there has been very limited formal acknowledgement of the harm done to so many, no moment of atonement, no national process of reconciliation and, all too often a neglect of our history.”

Perhaps a poet is most capable of explaining why we should go to Montgomery, or why we should take this first step.

Emblazoned on a wall in downtown Montgomery are these words by the poet Maya Angelou: “History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”