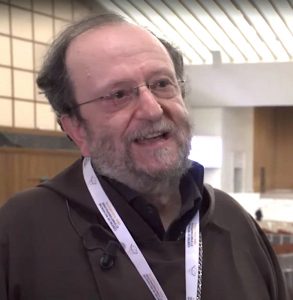

ROME — On May 1, Pope Francis appointed a 63-year-old Capuchin who served as an auxiliary bishop in Milan since 2014, Bishop Paolo Martinelli, as the new apostolic vicar of Southern Arabia, making him the Vatican’s envoy to the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Oman and Yemen.

Bishop Martinelli takes up his new post at a moment when the Vatican’s top diplomatic priority is the war in Ukraine. His boss, Italian Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican’s secretary of state, recently called the war a “sacrilege” and insisted that it cannot be justified on the basis of Christian values or the word of God, both cornerstones of the pro-Vladimir Putin rhetoric coming from Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and other Russian Orthodox leaders.

One might imagine, therefore, that Bishop Martinelli would immediately begin pushing the Vatican’s line on Ukraine, echoing its sharp criticism of what Pope Francis has called a “brutal” conflict.

And yet.

And yet, Bishop Martinelli has to be mindful of the fact that the UAE, where he’ll now be living, has been sympathetic to the Russian position, recently siding with its neighbor Saudi Arabia within the Gulf Cooperation Council to resist pressure from Washington to condemn the Russia invasion and to side with Ukraine.

Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed, the de facto ruler of the UAE, recently declined to take a phone call from U.S. President Joe Biden, but he reached out to Russian President Putin in early March shortly after the war began.

Most experts believe that the UAE, in tandem with Saudi Arabia, wants to avoid taking sides in the present conflict, concerned about preserving their relationships with Russia in the all-important energy sector and in other areas unrelated to the Ukraine crisis.

As a result, Bishop Martinelli may be slightly hesitant about pressing a line that may complicate his relationship with his new hosts right out of the gate.

In addition, while Bishop Martinelli is something of a stranger to the Middle East, he certainly knows two things about the new situation he’s set to inherit once his installation is complete.

The first is that because Christians are a tiny minority across the Muslim-dominated region, ecumenical ties among the various branches of Christianity are critically important, including relations between Catholics and the Russian Orthodox. When you’re up against a cultural majority that isn’t always positively inclined to Christianity, denominational differences, including those over geopolitics, often seem less important than in settings where Christians are the majority.

The second is that there’s a strongly pro-Putin mentality among many Middle Eastern Christians, including several of the Catholic bishops in the region, who feel that Putin and Russia have done more to protect and assist Christians in the Middle East than any other actor on the global stage, with the United States very much included.

Putin has styled himself as a modern-day Charlemagne, defending Christianity (especially Orthodoxy) wherever it’s threatened, and while many Middle Eastern Christians may be dubious about Putin’s rhetoric or motives, it’s hard to deny the concrete reality of Russian assistance on the ground.

Both of those factors mean that for Bishop Martinelli, figuring out how to approach the war in Ukraine in the context of his new assignment isn’t nearly as obvious as it might seem, say, in the United States or the other Western powers.

Indeed, it may be that Bishop Martinelli may be more inclined to play up aspects of Pope Francis’ verbiage on Ukraine that would be more congenial to his new hosts, such as the interview the pontiff recently gave to the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera, in which he appeared to blame NATO, at least in part, for the present conflict.

The pope said that perhaps Putin reacted because of “NATO’s barking at Russia’s gate ... I wouldn’t know if this provoked an ire but perhaps it facilitated it.”

The claim that NATO’s aggression in trying to expand and thereby encircling Russia with hostile forces has been a key element of the Kremlin’s defense of the Ukraine conflict.

In all fairness, Pope Francis also said that Patriarch Kirill “cannot become Putin’s altar boy,” which appeared to be a clear criticism of the fashion in which Patriarch Kirill has offered full-throated support of the war. He also groused that when he had a 40-minute video conference with the patriarch on March 16, the Patriarch Kirill spent half of it reading from a sheet of paper “with all the justifications for the war.”

Nonetheless, Bishop Martinelli might also emphasize the fact that Pope Francis said he should go to Moscow to meet Putin before he goes to Kyiv, which presumably would involve a meeting with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

“First, I have to go to Moscow, first I have to meet Putin ... I do what I can. If Putin would only open a door,” the pope said.

Depending on how one wishes to spin it, that comment could be seen as deferential to Putin, suggesting that he’s more consequential to the current drama than even the Ukrainian leader.

All this suggests that in a global Church with 1.3 billion adherents, scattered in every nook and cranny of the planet, nothing is ever simple — including how to respond to the defining geopolitical crisis of the moment, which just isn’t as simple as it may seem when refracted through an exclusively American or Western frame of reference.