The complexity of adulthood inevitably puts to death the naïveté of childhood. And this is true, too, of our faith. Not that faith is a naïveté. It isn’t. But our faith needs to be constantly reintegrated into our persons and matched up anew against our life’s experience, otherwise we will find it at odds with our life. But genuine faith can stand up to every kind of experience, no matter its complexity.

Sadly, that doesn’t always happen and many people seemingly leave their faith behind, like belief in Santa and the Easter Bunny, as the complexity of their adult lives seemingly belies or even shames their childhood faith.

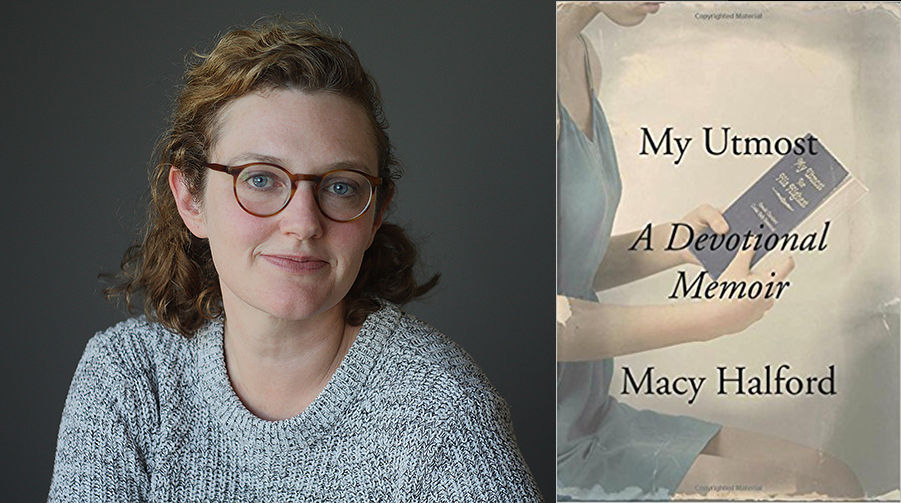

With this in mind, I recommend a recent book, “My Utmost: A Devotional Memoir” by Macy Halford. She is a young, 30-something writer working out of both Paris and New York, and this is an autobiographical account of her struggle as a conservative Evangelical Christian to retain her faith amidst the very liberal, sophisticated, highly secularized and often agnostic circles within which she now lives and works.

The book chronicles her struggles to maintain a strong childhood faith that was virtually embedded in her DNA, thanks to a very faith-filled mother and grandmother. Faith and church were a staple and an anchor in her life as she was growing up. But her DNA also held something else, namely, the restlessness and creative tension of a writer, and that irrepressible energy naturally drove her beyond the safety and shelter of the church circles of her youth, in her case, to literary circles in New York and Paris.

She soon found out that living the faith while surrounded by a strong supportive faith group is one thing; trying to live it while breathing an air that is almost exclusively secular and agnostic is something else. The book chronicles that struggle and chronicles, too, how eventually she was able to integrate both the passion and the vision of her childhood faith into her new life. Among many good insights, she shares how each time she was tempted to cross the line and abandon her childhood faith as a naïveté, she realized that her fear of doing that was “not a fear of destroying God or a belief; [but] a fear of destroying self.” That insight testifies to the genuine character of her faith. God and faith don’t need us; it’s us that need them.

The title of her book, “My Utmost,” is significant to her story. On her 13th birthday, her grandmother gave her a copy of a book that is well-known and much-used within Evangelical and Baptist circles, “My Utmost for His Highest” by Oswald Chambers. The book is a collection of spiritual aphorisms, thoughts for every day of the year, by this prominent missionary and mystic. Halford shares how, while young and still solidly anchored in the church and faith of her childhood, she did not read the book daily and Chamber’s spiritual counsels meant little to her. But her reading of this book eventually became a daily ritual in her life and its daily counsel began, more and more, to become a prism through which she was able to reintegrate her childhood faith with her adult experience.

At one point in her life she gives herself over to a serious theological study of both the book and its author. Those parts of her memoir will intimidate some of her readers, but, even without a clear theological grasp of how eventually she brings it all into harmony, the fruit of her struggle comes through clearly.

This is a valuable memoir because today many people are undergoing this kind of struggle, that is, to have their childhood faith stand up to their present experience. Halford simply shows us how she did it, and her struggle offers us a valuable paradigm to follow.

A generation ago, Karl Rahner famously remarked that in the next generation we will either be mystics or unbelievers. Among other things, what Rahner meant was that, unlike previous generations, where our communities (family, neighborhood and church) very much helped carry the faith for us, in this next generation we will very much have to find our own, deeper, personal grounding for our faith. Macy Halford bears this out. Inside a generation within which many are unbelievers, her memoir lays out a path for a humble but effective mysticism.

The late Irish writer, John Moriarty, in his memoirs shares how as a young man he drifted from the faith of his youth, Roman Catholicism, seeing it as a naïveté that could not stand up to his adult experiences. He walked along in that way until one day, as he puts it, “I realized that Roman Catholicism, the faith of my childhood, was my mother tongue.”

Macy Halford eventually regrounded herself in her mother tongue, the faith of her youth, and it continues now to guide her through all the sophistications of adulthood. The chronicle of her search can help us all, irrespective of our particular religious affiliation.

Oblate of Mary Immaculate Father Ronald Rolheiser is a specialist in the field of spirituality and systematic theology. His website is www.ronrolheiser.com.