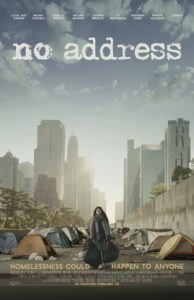

As someone who works in a homeless shelter, I found the newly released film “No Address” to be an earnest, praiseworthy attempt to put a human face on the social catastrophe known as homelessness.

I see the human face of homelessness on a daily basis. Sometimes, that face is not so pleasant. It makes it hard to raise money to keep the lights on. That explains why there is a sameness to the messaging that all homeless services organizations use, and that “No Address” drives home.

Phrases like “Anyone is just one disaster away from homelessness,” or an emphasis on victimhood are the coin of the realm in reaching out to donors. That is not to say that there are not legions of victims — especially women — living on our streets who are there due to a series of unfortunate circumstances outside of their control.

An array of dire circumstances coexists in this film. The film starts with a little girl making cookies with her mom. The mom has a seizure and dies in front of her. We fast forward years later to that girl returning from her high school graduation, diploma in hand, only to discover she has been locked out of her house because she has also “graduated” out of the foster care system.

Then we meet a young man who cannot live at home due to an abusive father. When that same young man loses his menial job, his circumstances turn even darker.

Other characters populate the homeless universe of “No Address,” like a mentally damaged older woman and her partner, who does not seem to have any issues other than he lives in a vacant lot. Finally, we meet a greedy real estate developer, played by actor William Baldwin. He lives with his wife and kids in a nice home that is actually beyond his means to support.

Baldwin moves the plot along by hiring thugs right out of central casting from a 1970s TV movie of the week until he loses his job, his family, his home, and winds up living on that same vacant lot as the other homeless characters we have met.

It is a noble thing to cast light on a problem that results in more than 70,000 individuals living on the streets of Los Angeles County. I understand why the film chose to portray its homeless characters as victims of their circumstances. But many times, the reality is much grimmer — and just like in the movie, people who work with the homeless every day and try to raise money to keep a shelter open just do not talk about the darker side.

Just like moviegoers, people who donate to homeless shelters want characters they can like. But what if some of our characters are not likeable? What if they are not victims, but victimizers? The shelter where I work has both.

As with everything, Jesus is the answer, and he gave me my answer a few Sundays ago at Mass in the Gospel of Luke: “And if you do good to those who do good to you, what credit is that to you? Even sinners do the same” (Luke 6 32:33).

There are donors I have met who stop donating because they see the issue as insurmountable, and many people have told me the homeless have done this to themselves. They are not entirely wrong. People who financially back movies and homeless shelters want the same thing — a return on investment. But the ROI Jesus talks about in Luke’s Gospel is something I’m sure very few people at the time wanted to hear. They still don’t.

If the script of “No Address” told the real story about homelessness, the movie would have never been made. We want our characters to be likeable. Jesus said the opposite.

The thing to keep in mind, which “No Address” gets in the way of, is that even in awfulness, there is always hope.

St. Dismas is the name given to the “good thief” crucified next to Jesus. I imagine his life was not a pretty picture — unlike Jesus, he was actually getting what he deserved. The thief two crosses over was also at the bottom of his spiritual pit. That thief continued to dig, Dismas asked for forgiveness, and even in his awfulness, Jesus only saw his true humanity.

It is not easy to love the unlovable, but Jesus never said things would be easy. Does it make a homeless person less human than I am? It makes him just as human as I am.

Showing the reality of brokenness and sin may not be good at the box office, but it is the script written in the four Gospels, and the one we are obliged to learn by heart.