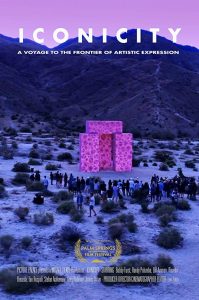

Director-producer Leo Zahn has made documentaries about mid-century architect William F. Cody and Frank Sinatra in Palm Springs.

Now he brings us “Iconicity.” The core theme, “Why are artists attracted to the [Southern California] desert? There is something here, call it a mystical energy or what have you, but it’s also very practical as to why certain art gets created only in the desert.”

I caught a screening in January at the Palm Springs Film Festival.

Shot over a period of 10 months in 2019, the cinematography is all saturated colors, sweeping aerial vistas, turquoise skies, shimmering mountains, landscapes that by day tend toward burned-out lunar, and velvet nights.

The music, courtesy of Spirit Production, lends the perfect out-of-time, slightly woo-woo touch.

In Niland, Leonard Knight spent decades painting Salvation Mountain. Slab City, a former Marine base, is now one of the largest vehicle squats in the country. East Jesus, another Salton Sea community, has likewise sprouted masses of sculpture, installations, and art made from desert-scavenged detritus.

Yucca Valley’s Christ Desert Park was the 10-year labor of Antoine Martin (1887-1961). In Borrego Springs, the shipping-label magnate Dennis Avery commissioned artist Ricardo Breceda to create a menagerie of giant metal sculptures: mammoths, dragons, insects.

There’s Noah Purifoy’s stupendous Junk Dada Outdoor Desert Art Museum, and the beautifully ordered quonset hut compound of Bobby Furst, sage, historian, and unofficial art mayor of Joshua Tree.

But the film really comes alive when it turns to the arts community at the annual three-day Bombay Beach Biennale, founded in 2016.

Bombay Beach is located on the eastern edge of the Salton Sea at 223 feet below sea level. From the late 1950s through the early 1980s, it was a “party place” known as the Desert Riviera. Its primary gathering place is, or was, a dive-bar restaurant called the Ski Inn. (The name refers to water skiing, not snow skiing).

Then the Salton Sea started shrinking. Hard times ensued. Derelict, salt-encrusted buildings dotted the landscape. A fish die-off began to occur each summer.

Artist Yassi Mazandi, creator of an eight-foot sculpture entitled “The Flower Skeleton,” notes, “When I first came here four years ago, I was struck by the decay … of the beach, the dead fish, the cats who had eaten the fish and died. … It reminded me of Mad Max in a weird way.”

But drawn by some mysterious force, inexorably, the artists kept coming. Tao Ruspoli, Biennale co-founder (and son of an Italian playboy prince), says, “There’s environmental catastrophe … economic issues … a kind of blankness. … Summer temperatures can reach 130. … There’s vandalism and theft and poverty. But artists seek this out.”

Many, some from New York, some from LA, have taken up part-time or full-time residence here. Their work is everywhere.

A red popsicle emerges from one spot in the sand, a giant hand from another. There’s a cock-eyed Ferris wheel, a mock drive-in filled with burned-out cars, a cow on a roof.

Stefan Ashkenazy, an LA hotelier and arts patron, is another Biennale co-founder. The genius of the event, he points out, is that it’s completely free: free food and drinks, no admission, no agenda.

But there’s bound to be friction. Wendell Southworth, former owner of the Ski Inn, guardedly admits that the artists have neatened and enlivened Bombay Beach, but that they also threaten the peace and quiet that drew the old-timers here in the first place.

Nonetheless, the borderline-crazed energy, the explosion of new ideas, and the peculiarly Southern California zeitgeist that manages to combine the laid-back and the obsessive in one gorgeous, last-gasp embrace are irresistible.

Thanks to the vibrant art scene, Bombay Beach now boasts a Natural History Museum, an Opera House, and the tongue-in-cheek Foundation Foundation.

Artist Greg Haberny in "Iconicity." (© PICTURE PALACE INC./IMDB)

Greg Haberny divides his time between New York and Bombay Beach. His method is to create a work, then destroy it with demolition saws, light it on fire, soak it in water, and with the ashy result, form a kind of paint with which he makes another piece of art. The result is a surprising, jittery yet controlled beauty.

Fellow artist Randy Polumbo observes, “He brutalizes his material. You think you couldn’t make anything good out of it, that he’s somehow run the life out of it. But then he takes it back from the dead and makes it into some little piece of poetry that has this incredible energy still in it.”

That’s actually a pretty good description of the Resurrection.

Haberny adds, “There’s a freedom out here that allows me to just dig into the environment. Just … eat it … alive. Just go for it.”

Zahn reports that he expects “Iconicity” to be available for streaming on Amazon and other platforms by April 2020. It screens March 27 at the Rancho Mirage Library.

The film is worth seeing alone for the closing scene with its mad-desert-circus procession toward the setting sun.

When the Salton Sea has dried up, when Bombay Beach and Palm Springs and Los Angeles have sunk into the sand, or the Pacific Ocean, the procession, one senses, will continue.

A guy on stilts will still be tooting a tin horn. A beautiful woman in a ball gown will still be levitating. And Randy Polumbo’s “Lodestar,” a towering sculpture fashioned from a gleaming upside-down airplane fuselage and surmounted by a kind of demented jeweled crown, will — somewhere, somehow — still be shining in the velvet darkness.