Aug. 6 and Aug. 9 mark the 78th anniversary of the dropping of atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of, respectively, Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, were killed on those days in 1945. Both cities, within the limits of the bomb sites, were reduced to rubble.

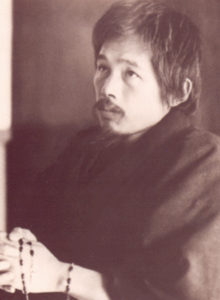

Takashi Nagai (1908-1951), a Catholic convert, Japanese doctor, radiologist, and survivor of the bomb, wrote the popular post-World War II book, “The Bells of Nagasaki.”

In “A Song for Nagasaki,” biographer Paul Glynn, SM, charts Nagai’s spiritual evolution from atheist to ardent Catholic: a follower of Christ who came to believe that peace requires a radical turning of the other cheek.

Born to highly educated parents in the western Japanese city of Matsue, first son Takashi was the apple of his parents’ eyes. Steeped in the Shinto religion and the Japanese ethos that condemned surrender of any kind, Nagai studied medicine at Nagasaki Medical College.

The bells at the nearby Urakami Cathedral that rang the Angelus three times a day irritated him. How crass for a modern Japanese to be reminded not only of religion but a foreign religion at that! When a professor showed a corpse in class and opined that a human being is nothing more than physical properties, Nagai thoroughly concurred.

But upon the death of his beloved mother in 1930, Nagai began to read Blaise Pascal’s “Pensées.” “For five years,” he later wrote, “I was deeply troubled by a little voice I heard, waking and sleeping: ‘What is the meaning of our lives?’ ”

Looking for a home in which to board, he happened upon the Moriyama family, whose Christian roots extended back 300 years. Through frightful persecution, poverty, and exile, their Catholic faith had stood firm.

Poised to give a speech at his graduation from medical school, Nagai partied the night before, got soaked with rain, and developed meningitis. He almost died and lost hearing in his right ear.

Radiology was one of the few areas of medicine in which he was now equipped to practice, and he quickly became fascinated by the subjects of atomic structure and nuclear fission.

At a midnight Christmas Mass he attended with the Moriyamas, Nagai felt disturbed when the worshippers sang the Credo. Why? he wondered. Was it because ordinary people could take an uncomplicated stand for goodness and truth, while he was a footloose academic and ethical dilettante who could not?

He was particularly moved by the beauty, grace, and religious ardor of the Moriyamas’ daughter, Midori. The two fell in love and when in 1933 Nagai went off to war in Manchuria, Midori was waiting for him upon his return, rosary in hand.

Having continued reading Pascal, and the Gospels, Nagai also met with a priest. He was baptized on June 9, 1934, and confirmed that December.

Meanwhile, he and Midori married. The couple would go on to have four children, a boy and three daughters, the second of whom died shortly after birth. In another devastating loss, Nagai’s father died around the same time.

Nagai was working in his office on the morning of Aug. 9, 1945. Flying glass from the bomb severed an artery in his temple, and he began gushing blood. He nonetheless immediately set about rescuing and organizing the wounded.

Returning to the family home, he found that Midori had been incinerated. Among the charred remains of her skull, hips, and backbone, Nagai spotted a blob of metal: the chain and cross from the rosary she had always carried.

His children had lived. Many others had survived with burns, oozing wounds, and radiation-induced leukemia. He threw himself into helping them, and into writing the 20 books he would produce in his remaining five years.

By Sept. 8, Nagai himself had begun to exhibit signs of extreme radiation sickness. He was given a death sentence and suffered chronic and ever-worsening illness until the end of his life.

Interestingly, however, he did not view the discovery of atomic energy as the fatal opening of a Pandora’s box: perhaps the energy could someday be used to light people’s homes. Nor did he engage in anti-Western sentiment.

At a Requiem Mass for the Dead said at the ruined Urakami Cathedral on Nov. 23, 1945, instead he introduced the concept of “hansai,” the Japanese word for a burnt offering, or the Bible’s Holocaust.

“It was not the American crew, I believe, who chose our suburb. … Was not Nagasaki the chosen victim, the lamb without blemish, slain as a whole burnt offering on an altar of sacrifice, atoning for the sins of all the nations during World War II?”

It’s an astonishing notion: Perhaps only a follower of Christ could have conceived it.

Along with his soldier friend Ichitaro Yamada and other workmen, Nagai also helped to unearth the buried French Angelus bell. The church was eventually rebuilt and is now known as Immaculate Conception Cathedral.

Avoiding easy platitudes, Nagai continued to aver that peace is a noble ideal — and also an arduous one.

William Johnston, a specialist in Japanese Zen, noted that in the end Nagai was a mystic. “He attempts a theology born of cruel suffering and painful conversion of heart … with his message of love he takes an honored place beside … great prophets.”