Intellectual confusion resembling a smog of the mind has been a deadening presence in Catholicism in the years since the Second Vatican Council. But here and there amid the swirling mists of bad arguments and lame analogies, a small yet significant body of Catholic intellectuals has stood firm in defense of clear thinking and good sense.

For me at least, three stand out: Ralph McInerny, Germain Grisez, and Jude Dougherty. The news that Dougherty, longtime dean of the school of philosophy at The Catholic University of America, had died in early March, moves me to pay tribute to them for their contributions to the Church they loved.

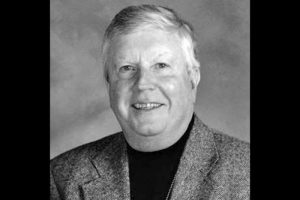

McInerny, who died in 2010, was probably the best known of them for writing the Father Dowling mysteries that served as the basis for a popular TV series. Along with writing fiction, however, McInerny, a prodigious worker, also produced a score of serious books on philosophical and religious topics while being a consistent voice of courageous clarity in troubled times during his long career teaching philosophy at Notre Dame. (He also had a finely honed sense of humor, visible in the subtitle of his primer on St. Thomas Aquinas: “A Handbook for Peeping Thomists.”)

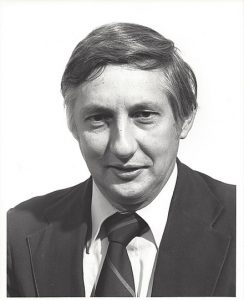

Grisez, a good friend with whom I was privileged to collaborate on several writing projects, died in 2018. He began his teaching career at Georgetown University, but spent his latter years at Mount St. Mary’s University, where he taught seminarians and wrote his brilliant three-volume magnum opus of moral theology, “The Way of the Lord Jesus.” His contributions to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, though not publicly recognized, were enormous.

A deeply kind man to whose generosity toward honest inquirers many of his former students testify, he nevertheless was ferocious in spearing sloppy thinking from whatever source, no matter how highly placed.

Jude Dougherty was linked to Catholic University for almost his entire adult life, first as an undergraduate and then graduate student, then, starting in 1966, as a professor of philosophy, and finally as the first lay dean of the university’s school of philosophy, a position he held for more than 30 years.

Like McInerny and Grisez, he wrote many books (e.g., “The Logic of Religion” and “The Nature of Scientific Explanations”). But probably his most significant contribution was to maintain the school of philosophy as a trustworthy exponent of the best in the Catholic intellectual tradition at a time when the forces of dissent often appeared to be in control of the university.

Today, of course, under leadership of its current president, John Garvey, Catholic University is a solidly Catholic institution embodying high standards of excellence. But by no means was it always so, and Dougherty’s grit and integrity were indispensable in those dark days.

McInerny and Dougherty were fervent Thomists who cherished the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas and labored to transmit it to new generations. Grisez readily admitted St. Thomas’s role in shaping his own thinking, but eventually he concluded he was not himself a Thomist — a judgment borne out by the “New Natural Law Theory” that he and philosopher John Finnis created and that now plays a key part in contemporary ethical thinking.

It would have been well worth the price of admission to be there if the three men, who knew one another well, had ever come together to argue about Thomism and share views on the future of Catholic higher education. Absent that, we have the important intellectual legacies that each of them left. And that is very much.