Recently I watched a 24-minute documentary short, directed by Sofia Coppola, on the post-COVID-19 return of the New York City Ballet to its home at the David H. Koch Theater.

Principal Gonzalo Garcia dances alone in a studio to a Chopin solo. Backstage, Ashley Bouder and Russell Janzen glide through Balanchine’s “Duo Concertant.” In the theater’s promenade, Maria Kowroski and Ask la Cour dance an excerpt from Balanchine’s “Liebeslieder Walzer.” Anthony Huxley, alone on stage, introduces a new “Solo” by the company’s resident choreographer and artistic adviser Justin Peck.

With the finale, Balanchine’s “Divertimento No. 15,” several members of the corps reassemble, the film goes from black-and-white to color, and the return home is complete.

The film was rapturously reviewed by The New York Times dance critic Gia Kourlas. And who isn’t thrilled at the thought of once again seeing ballet in the flesh?

And yet, somehow, the footage left me a teeny bit cold. I admired, and rejoiced, but until the finale, I wasn’t moved. I didn’t feel an intelligent, unifying force.

This could have had something to do with the fact that I had also recently rewatched “A Dancer’s World,” another documentary short, this one made in 1957, featuring Martha Graham and her Dance Company.

Graham (1894-1991) danced, taught, and choreographed for more than 70 years. She was a diva and a force of nature who is widely acknowledged to have reshaped modern dance.

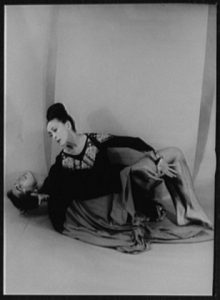

This film, too, starts backstage, as dancers stretch, bend, and bow in shadow. Then Graham’s voice cuts in: cultured, patrician. “A theater dressing room is a very special place. It’s where the act … [dramatic pause] of theater begins.” The makeup, the magic, the ritual.

Sitting before her dressing room mirror, Graham sports a lacquered bun run through with what looks like a tuning fork but is apparently a headpiece for the part of Queen Jocasta in “Night Journey,” her retelling of Sophocles’ “Oedipus Rex” by way of Freud and Jung, set to music by American composer William Schuman with costumes designed by Graham and a set by the acclaimed Japanese American sculptor Isamu Noguchi.

“You do not want to fail, in either clarity or passion. You give all your life to doing this one thing. It sounds grim, it sounds frightening.”

The film continues in that mesmerizing vein, coming right up to the edge of parody. But Graham’s bearing, discipline, and focus forfend parody.

Her autobiography, “Blood Memory,” begins like this:

“I am a dancer.

“I believe that we learn by practice. Whether it means to learn to dance by practicing dancing or to learn to live by practicing living, the principles are the same. In each it is the performance of a dedicated precise set of acts, physical or intellectual, from which comes shape of achievement, a sense of one’s being, a satisfaction of spirit. One becomes an athlete of God.”

It’s impossible to imagine a contemporary dancer uttering such words, belief in God having gone the cultural way of the dodo.

In fact, the way Graham speaks of the vocation of dance reminded me of nothing more than Christ’s words in John 15:16: “You did not choose me, but I chose you and appointed you so that you might go and bear fruit — fruit that will last.”

“People have asked me why I chose to be a dancer. I did not choose. I was chosen to be a dancer, and with that, you live all your life. When a young student asks me, ‘Do you think I should be a dancer?’ I always say, ‘If you have to ask, then the answer is no.’ Only if there is one way to make life vivid for yourself and for others should you embark upon such a career.”

In Graham’s day, people read. It was taken for granted that an artist, of any stripe, would have been steeped in the classics, taken music lessons of some kind, been acquainted with painting, philosophy, poetry — for example, Eliot’s “Four Quartets”:

“When a dancer is at the peak of his power he has two lovely, fragile, and perishable things. One is the spontaneity that is arrived at over years of training. The other is simplicity, but not the usual kind. It is the state of complete simplicity costing no less than absolutely everything, of which T.S. Eliot speaks.”

This clarity of action and thought allowed her to sidestep ideology: “I tried to show the three aspects of women in ‘El Penitente,’ my ballet of 1940. Every woman who is worth anything has some of these in her. Every woman has that quality of being a virgin, of being the temptress-prostitute, of being the mother. I feel that these, more than anything, are the common life of all women. Not politics.”

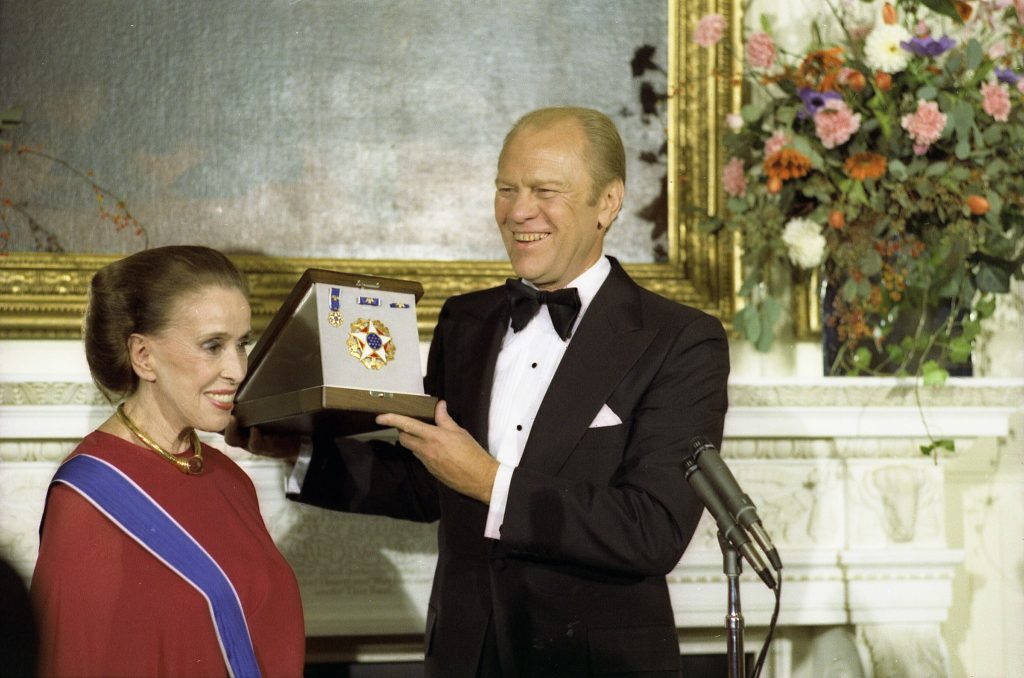

In later life, her body deteriorating with age, Graham fell into depression and turned for a time to alcohol. But her indomitable will to live triumphed: She stopped drinking in 1972, embarked on a creative renaissance, and choreographed for almost 20 more years.

“The next time you look in a mirror, just look at the way the ears sit next to the head; look at the way the hairline grows; think of all the little bones in your wrist. It is a miracle. And the dance is a celebration of that miracle.”