Iconography is pretty important to the Church. It is also pretty important to societies in general, and our monuments and our statues say a lot about ourselves.

Gleeful mobs cheering as the latest statue of a Confederate general is pulled down may produce a sense of self-righteous accomplishment for some, but when one form of destruction becomes acceptable, it is only a matter of time before that acceptance spreads to less-justified targets.

St. Junípero Serra has found himself in the crosshairs of this anarchy algorithm, his “sin” being little more than being a man from the 18th century. Not only was St. Junípero’s statue toppled in San Francisco, but the mob turned its wrath on President Ulysses S. Grant, whose statue suffered the same fate.

The mere thought of having to defend these two historical giants against a mob gives the mob more credibility than I am willing to cede. And besides, a canonized saint and a man who engineered the defeat of the Confederate States of America and who helped abolish slavery in the United States doesn’t need my help.

A country’s history is a lot like families: we don’t get to choose what took place in the past, and we don’t get to choose our ancestors. But if we are smart enough and humble enough, we do get the opportunity to learn from ancestors.

That’s how we can venerate an 18th-century priest without demanding he be a 21st-century man.

Whatever imperfections he had, St. Junípero’s primary purpose in life was to win souls for Christ, the top priority of the Catholic Church throughout its 2,000 year history. That’s what guided his actions when ministering to the souls of the native population of California, and he did so at a time when many of his countrymen did not see these people as equals, neither in the eyes of man nor God.

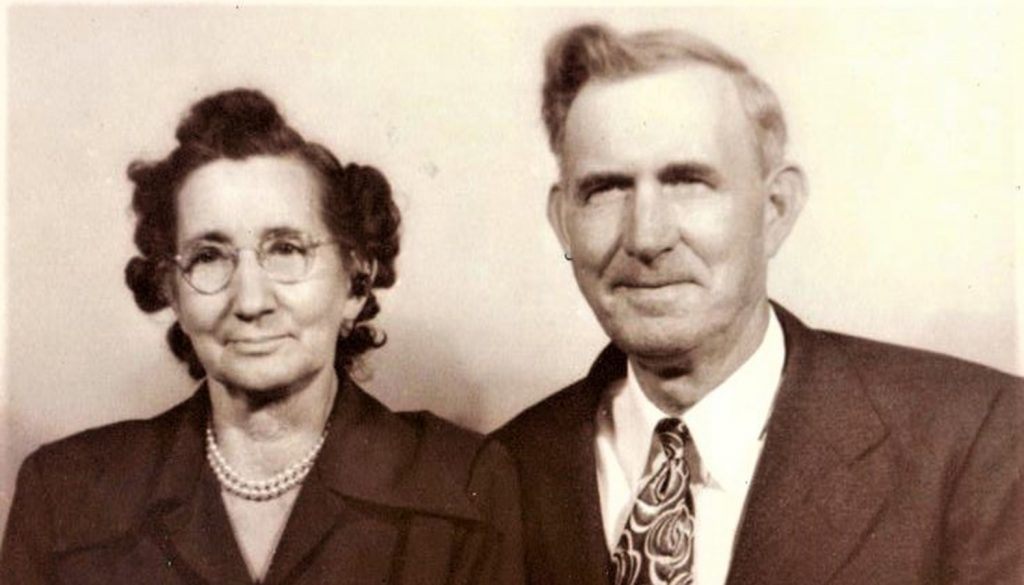

I have a case of more complicated iconography in my own living room. There, in a place of honor, is a photo of a man who was a dyed-in-the-wool racist.

My grandfather was a man of the South. He was born in 1883 in Arkansas. He had forebears who fought in the Civil War for the Confederacy. My grandfather, the only grandfather I knew, believed in a system of “separate and unequal” and went to his grave in 1963 believing no black person could ever be his equal or should ever be his neighbor.

And I loved him.

When my mom would make her regular visits to her parents’ house – they lived only a block away from us as my grandfather had to give up family farming in Arkansas several years before — I was always in tow.

His garage was a workshop of wonders and I would sit and watch him carve wood and repair gardening equipment with his elegant long fingers. I was mesmerized when he would take out his pocket knife and cut a sliver from a brick-like chaw of tobacco and wedge it into the side of his mouth.

I don’t know if we ever said more than a hundred words to each other. I only knew he seemed to like me being around and I liked being around him, too.

But I also knew he used language we weren’t supposed to use at home when it came to identifying someone by their race, especially if that person was of African heritage. Our dad and mom would always caution us about that either before or after a visit.

Later in my life, listening to stories about my grandfather from my mother, aunts, and uncles, I got a fuller picture of this man. He was not any more anti-Catholic than he was anti-religion in general. He also had very little use for foreigners.

But as the Irish Catholic grandson being bounced on his knee, I was blissfully ignorant of all that. I only felt his love and affection. My older siblings, who spent a lot more time with this man than I did, would tell the same story.

Life is complicated. Yes, my grandfather believed things that are not defensible. But if I could ever be as good a father as he was, as good a son, as good a husband and as good a grandfather as E.J. Taylor, I would die a man of substance.

So, I will not be taking the picture of my grandfather down anytime soon. I will pray for his soul. I will thank God for the love this man showed me. And I will ask God to give me the grace to be more like my grandfather when it comes to things like integrity, love, and respect.

Last, I will thank my grandfather for the gift of his daughter, my mom, who learned those lessons of integrity, love, and respect on his knee, which gave her the tools to use in her own journey of faith. That journey led her to an Irish Catholic man from Missouri, and eventually to my deposit into the Catholic Church.

If I had my grandfather’s talent for woodworking, I’d make a statue.