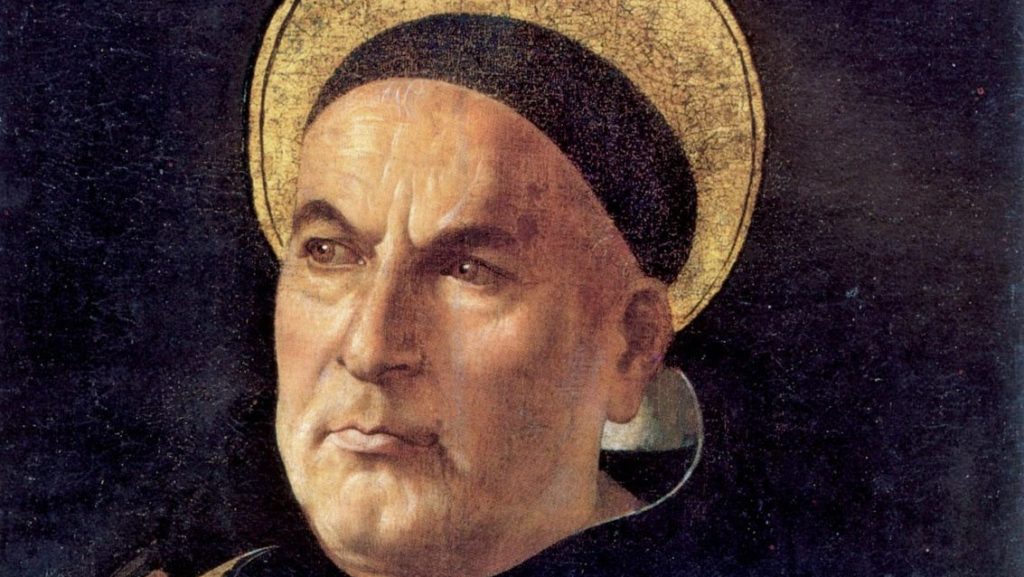

St. Thomas Aquinas was a champion of reason. He was a man whose philosophy was expressed in language precisely technical and ploddingly comprehensive.

For all this, however, he was not a rationalist. He was not Aristotle dressed up in priestly vestments. And he was definitely not a bore.

He was a priest of the 13th century, a member of the newly established Order of Preachers, the Dominicans. He was descended from the aristocracy of southern Italy. He was quiet and inclined to scholarly research and writing. For many years he taught theology at the University of Paris. He was a prolific writer, keeping multiple secretaries busy simultaneously with his dictation. He produced thousands of words per day of his adult life. His most famous work is his great, unfinished Summa Theologica (“Summary of Theology”), perhaps the most comprehensive systematic account of Christian theology ever attempted.

A quiet, humble man, he had epic and holy ambitions. In order to achieve them, he needed to observe the rigorous disciplines of philosophical theology. He had to be passionate about a language that very few people find exciting.

Still, I believe that Aquinas is fundamentally a biblical theologian. In fact, many of his biographers tell us that he would have described himself primarily as a teacher of Scripture.

As he himself said, “Our faith receives its surety from Scripture.” Why is Scripture so uniquely authoritative? Aquinas answers: “Because the author of Sacred Scripture is God, in whose power it is to accommodate not only words for expressing things, which even man is able to do, but also the things themselves.”

God “writes” the world, then, the way people write words. Thus, nature and history are more than just created things; they have more than just a literal, historical meaning. God fashions the things of the world and shapes the events of history as visible signs of other, uncreated realities, which are eternal and invisible. Aquinas says, “As words formed by man are signs of his intellectual knowledge, so are creatures formed by God signs of his wisdom.”

But because of sin’s blinding effects, the “book” of nature must be translated by the inspired Word of Scripture. Nature, since the fall, cannot be truly understood apart from Scriptures.

Consider his Treatise on Law. That treatise is interesting because, like many sections of the Summa, Aristotle is quoted often. But, when you total up the number of quotations, you find that 724 quotations are from Scripture and only 96 from Aristotle.

A contemporary and a fellow Dominican, Friar Bernard Gui, said in praising St. Thomas: “O happy soul whose prayer was heard by God in his mercy, who thus teaches us, by this example, to possess our questioning souls in patience, so that in the study of divine things we rely chiefly on the power of prayer!”

We honor him on his feast day this year, as every year, on Jan. 28.