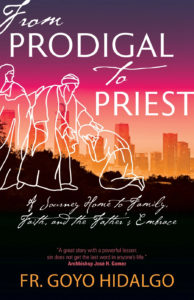

Father Goyo Hidalgo, an LA archdiocesan priest, has written a book endorsed by Archbishop José H. Gomez. It’s called “From Prodigal to Priest: A Journey Home to Family, Faith and the Father’s Embrace” (Ave Maria Press, $14.95).

Hidalgo was born and raised in Spain in a deeply Catholic culture and family. He had an intellectually disabled brother who required 24/7 care. He revered his mother, strict but loving, who prayed the rosary and told him often that if he forgot to talk to God daily, then one day he would forget about him completely.

In the village where he grew up, priests were looked up to, emulated, admired. “Half our lives revolved around services that required a priest.” Desiring to follow in the footsteps of Padre Pio, he left home at the age of 10 and entered a seminary in Toledo.

After a few years, he met a girl, doubted his vocation, and quit. Back at public school, he was a nobody. So he quit that, too, at which point his father put him to work in the vineyards. That didn’t sit well either, so after six months he was accepted to a school in Madrid, began to pursue a degree in linguistics, and in the big city at last, began to dream big: money, freedom, traveling the world.

After graduating, he got the job of his dreams teaching high school in LA. “When I moved to the United States,” writes Hidalgo, “all my intimacy with God and, in a way, all my Catholic heritage was moved to somewhere remote in my conscience.”

Mass went by the wayside. He started drinking, partying, and throwing money around. His dog was more important to him than prayer. He and his friends would drive by a church and ridicule the losers who believe in fairy tales.

When he talked to his mother back home, he lied and pretended he was still faithful. He began to feel bad about himself, to experience the emptiness and hopelessness of the prodigal son.

One April morning in 2005, he turned on the TV and happened to catch the funeral of Pope John Paul II. He began to “cry like a little boy, alone and lost.”

Feeling an overwhelming urge to converse with God, he wanted to come clean about his failures and pain. But though he tried to pray, the words stuck in his throat. For 10 years, he had turned his back on God. He had “squandered his birthright,” again like the prodigal son.

So he did what any true child of God and follower of Christ would do. He called his mother back home in Spain and poured out his heart.

“I will teach you to pray the rosary again,” she said, “like when you were a little kid.”

And thus began Hidalgo’s journey home — which as he notes is “rarely steady or straight.”

Gradually, in fits and starts, he pulled away from his drinking friends. He called an old friend from seminary who suggested that he go to confession. Confession! Was the guy crazy? He didn’t even remember how confession went — the words, the prayers. But he went anyway — and afterward, uncontrollably wept.

He felt an overwhelming urge to attend daily Mass, and he did that. He began to search for a quiet chapel, without noise or distractions. Late to Mass one day, he exited the freeway at an unfamiliar street, chanced upon a sign reading “Pauline Books and Media” and stopped in. As if she’d been waiting for him, a Filipino nun met him at the door. “I am happy to see a young man coming into our store today,” she said. “Have you thought of becoming a priest?”

Then she took him by the hand, led him to a door near the back, and added, “Before you shop you must visit our chapel and say hello to Jesus.”

As C.S. Lewis said, “If [Christianity] offered us just the kind of universe we had always expected, I should feel we were making it up. But, in fact, it is not the sort of thing anyone would have made up. It has just that queer twist about it that real things have.”

“And so the romance began,” writes Hidalgo. That chapel became his second home. He went every day and sometimes spent hours. When the prayer dried up, the sisters taught him about desolation, and he learned to show up to prayer whether he felt like it or not. He learned that when helping someone in prayer, “Don’t just pray for them, pray with them.”

He stopped gossiping, swearing, and backstabbing. His friends noticed a change in him. He broke it to them that he now believed in God, that he was attending Mass. For the most part, his friends accepted it. But he was dying to his old self, and he knew that would be a daily, lifelong battle.

I won’t spoil the story of how he discerned his vocation, struggled to incorporate his extroversion into the contemplative life in seminary, got ordained, and found his way to the parish of St. Philomena in Carson, where he is now associate pastor.

Read it yourself — and remember the parable of the shepherd who left the 99 in the wilderness, and when he found the one lost sheep, carried it home on his shoulders, rejoicing.