That there’s a rising tide of anti-Christian persecution around the world in the early 21st century is an empirical fact. Christians are hardly the only ones facing threats, of course, but because of their numbers and the zones of their greatest growth, numerically they tend to be more exposed to risk than virtually any other minority group.

In January, Open Doors International, a nondenominational advocacy group on behalf of persecuted Christians, released its annual “World Watch List.” Once again, it found that more than 200 million Christians face high, very high, or extreme persecution.

The question isn’t whether anti-Christian persecution is real, but what to do about it, and on that score well-intentioned people can and do disagree.

One instinct, widely shared among the activist community, is to go on the offensive — to insist on sanctions for offender countries, to denounce the architects of persecution, to support robust military and security crackdowns on terrorist groups and militants that target Christians, and to demand that when the source of the persecution is religious, leaders of that faith step up.

To take a concrete for-instance, many activists would like to see the United States and other Western nations impose sanctions on nations such as China and India that have a dubious record on religious freedom generally, and their Christian minorities in particular.

Activists also typically insist that both Western governments and Western religious leaders should be tougher with Muslim leaders, insisting that they speak out in defense of Christians, especially in the Middle East, and do far more to promote a climate of tolerance — rejecting school textbooks that foster anti-Christian prejudice, for instance, eliminating blasphemy laws, and exercising tighter vigilance over the kind of rhetoric used in mosques and madrasahs.

In the face of the appalling suffering Christians experience in many parts of the world, often exacerbated by indifference or outright connivance on the part of both government and spiritual leaders, those seem to be utterly reasonable requests.

Others, however, are equally concerned about religious freedom and the welfare of Christians, but prefer the carrot over the stick.

The right answer to confrontation, as they see it, isn’t more confrontation but rather dialogue. The trick is to reach out to responsible parties, building relationships and working to remove the misconceptions and biases that often drive persecution.

Angry rhetoric and punitive measures, they fear, risk making things worse, whereas the only long-term exit strategy is friendship. Once that’s accomplished, they feel, “demands” for Christian rights will seem more like natural gestures among friends.

All of which brings us to Pope Francis, who’s very much in the carrot camp when it comes to fighting anti-Christian persecution.

Certainly no one can accuse the pontiff of a lack of concern, as Christian suffering has become a staple of his rhetoric. Last December on the feast of St. Stephen, Christianity’s original martyr, Francis’ language was characteristically dramatic.

“Even today the Church, to render witness to the light and the truth, is beset in various places by hard persecutions, up to the supreme test of martyrdom,” Francis said. “How many of our brothers and sisters in the faith suffer abuses and violence, and are hated because of Jesus!

“I’ll tell you something,” the pope said. “The number of martyrs today is greater than in the early centuries. When we read the history of the early centuries, here in Rome, we read about so much cruelty to Christians. It’s happening today too, in even greater numbers.”

Pope Francis visited the Memorial of New Martyrs at the Church of St. Bartholomew on Rome’s Tiber Island April 22, in another effort to ensure their legacy and sacrifice is not forgotten.

Yet Francis is typically nonconfrontational in his approach to the issue — preferring when it comes to Islam, for instance, to praise it as a “religion of peace” and to deny that there is such a thing as “Islamic terrorism,” rather than railing at the failures of Muslim leaders to keep Christians safe.

That discretion often drives some people, including some victims of anti-Christian oppression, to distraction. I vividly recall sitting with a group of Catholic bishops from the Middle East last August, shortly after Francis had delivered the “religion of peace” sound bite on the papal plane coming back from World Youth Day in Poland, and asking for their assessment.

Most of what I heard, to be frank, can’t be reproduced here, but let’s just say it wasn’t terribly favorable.

However, Catholicism is not an either/or tradition, but both/and. In that light, it’s possible to see the contrast between hawks and doves on anti-Christian persecution not as contradictory, but rather complementary.

In a sense, one could argue that Pope Francis is providing “cover” for activists and other Christian leaders to push back as loudly and aggressively as they want, because no one could style it as some sort of militant Christian crusade as long as he’s in charge. Francis makes clear that the desire of the Church isn’t conquest but relationship — in his now-familiar terms, building bridges rather than walls.

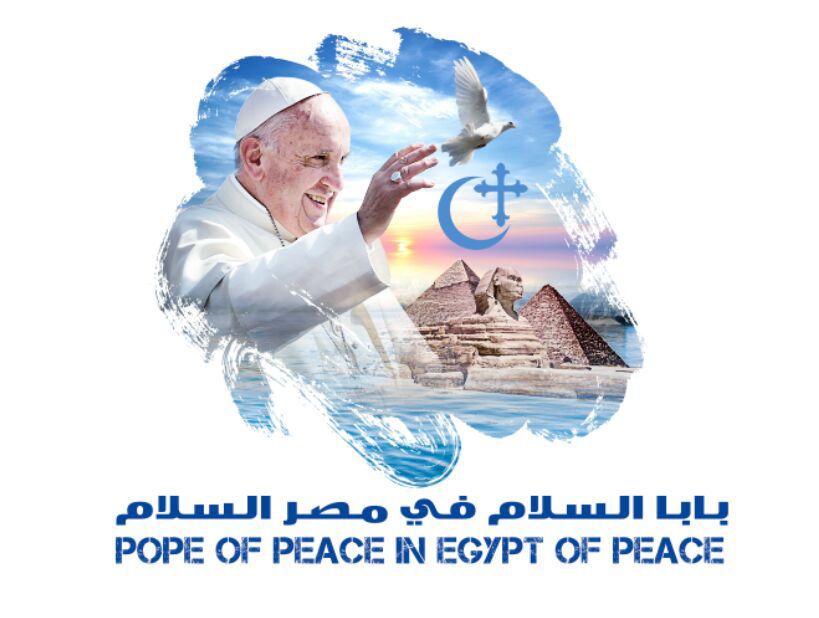

No doubt, that will be the spirit of his trip next weekend to Egypt, the highlight of which will be an address at a conference on peace at Al-Azhar, the most important center of learning in the Sunni Muslim world, in the company of both Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople and Pope Tawadros II, leader of Egypt’s Coptic Orthodox church.

Equally no doubt, the climate of conviviality we’re likely to see in Cairo will irritate some, who’d like to see Francis use that platform to call out the Islamic clerical establishment in Egypt for not doing more to combat anti-Christian prejudice.

Another way of looking at it, however, is that everyone else is freer to push back because Francis is so busy reaching out.

In any event, it doesn’t seem Francis is likely to change course, so those invested in the cause of defending suffering Christians have a choice to make — either embrace the pontiff’s bridge-building campaign, or spend a significant chunk of time being frustrated by it. It’s hard not to think the former is the more constructive choice.