ROME — Imagine that two different governments are engaged in crackdowns against the Catholic Church, including putting priests and bishops in jail, limiting or even expelling religious orders, and subjecting Catholic organizations of all stripes to tight vigilance and control.

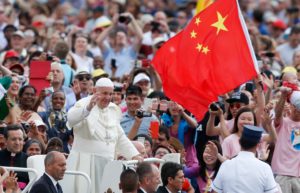

In the abstract, one might think that since the offenses are similar, the Vatican response would be the same, too. Yet the reactions of Pope Francis and his advisers to Nicaragua and China reveal contrast rather than continuity.

With Nicaragua, the Vatican’s criticism has been clear, constant, and increasingly acerbic; when it comes to China, such pushback has been conspicuous mostly by its absence.

In the end, the explanation for this contrast probably lies not in moral analysis but geopolitics: China is a superpower and Nicaragua isn’t. Bluntly put, Francis needs to stay in Beijing’s good graces far more than Managua’s.

Pope Francis has spoken out on Nicaragua several times this year. On New Year’s Day, he prayed for Nicaragua, “where bishops and priests have been deprived of their freedom,” assured the families and friends of those imprisoned of his closeness and prayer, and voiced hope “that the path of dialogue will always be sought to overcome difficulties.”

A week later, in an annual speech to diplomats, he said the situation in the country “remains troubling: a protracted crisis with painful consequences for Nicaraguan society as a whole, and in particular for the Catholic Church.”

“The Holy See continues to encourage a respectful diplomatic dialogue for the benefit of Catholics and the entire population,” he said.

Shortly after, Bishop Rolando Álvarez of Matagalpa, who had spent over a year in prison, and 18 others, were released from prison and exiled to Rome, where they were welcomed personally by Vatican Secretary of State Pietro Parolin as official guests of the Holy See.

When it comes to China, on the other hand, Francis and his aides have been much quieter. Nothing was said when pro-democracy protests erupted and were quickly quashed in Hong Kong between 2019 and 2020; when a new national security law was imposed in the city which was used to arrest and charge several high-profile activists, including several prominent Catholics; or when Cardinal Joseph Zen, the retired bishop of Hong Kong, was arrested and convicted by a Hong Kong court with several others in 2022 for their pro-democracy advocacy.

The Vatican barely let out a whisper last year when Chinese authorities repeatedly violated the terms of the 2018 provisional agreement between China and the Holy See on episcopal appointments.

To the consternation of many, the terms of that agreement remain secret, prompting criticism that it has induced the Vatican to remain mute on China’s record on human rights and religious freedom.

Last spring, the Vatican simply issued brief statements voicing concern after China made several unilateral transfers of bishops without Rome’s knowledge or consent, including the November 2022 transfer of Bishop Pen Weizhao to the Diocese of Jiangxi and the April 2023 transfer of Bishop Shen Bin to Shanghai.

Rather than condemning such blatant violations of their agreement, Vatican officials have instead used these transfers to push forward efforts to strengthen ties.

In the case of the unauthorized transfer of Shen Bin to Shanghai on April 4, 2023, the pope’s approval was only announced three months later. That announcement was accompanied by an interview published by Vatican News, the Holy See’s official information platform, in which Parolin expressed hope that a resident papal representative to Beijing could soon be named.

Francis also offered a direct friendly greeting to the “noble Chinese people” during his final Mass in Mongolia last summer, and he also recently held a meeting with a delegation from the National Federation Italy-China in honor of the Chinese New Year.

With the 2018 provisional agreement up for renewal for a third time this fall, it appears there is an effort to accelerate the move toward strengthened ties, with more bishops being named in the span of one week at the end of last month than have been named for the entire duration of the 2018 agreement thus far.

Last month, the Vatican announced the suppression of the apostolic prefecture of Yiduxian in China and the establishment of the Diocese of Weifang, marking the first formal creation of a new diocese by the Holy See in China since the Communist revolution in 1949.

The Jan. 29 Vatican statement said the decision to replace the Yiduxian prefecture was made on April 20, 2023 — notably, in the interim between the unauthorized transfer of Shen Bin and the pope’s acceptance of that move — and that at the same time, Bishop Anthony Sun Wenjun, 53, had been appointed to lead the diocese.

Days before, on Jan. 25, the Vatican announced the ordination of a new bishop for the Diocese of Zhengzou, who it said had been appointed by the pope on Dec. 16, 2023 “in the framework of the Provisional Agreement between the Holy See and the People’s Republic of China.”

Then again on Jan. 31, the Vatican announced a third episcopal appointment in China, revealing that Bishop Pietro Wu Yishun, named bishop of the Apostolic Prefecture of Shaowu, Minbei, in the province of Fujian on Dec. 16, 2023, had been ordained a bishop earlier that day.

The most important takeaway from this slew of appointments — together with last year’s appointment of a resident papal representative to Vietnam — is that the Vatican is eager for diplomatic progress in the Far East.

While the pope’s words on Nicaragua resounded in news headlines, his actions on China have also sent a clear message about his intentions and priorities, and as the old adage goes, actions often speak louder than words.