Anyone familiar with Catholic social teaching knows it’s often not a good fit for the left versus right dynamics of American culture, and we got another reminder of the point on Jan. 31 with President Donald Trump’s pick of Neil Gorsuch, an Episcopalian, as the next associate justice on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Considered a reliable conservative on most issues, Gorsuch seems likely to align with the Catholic Church’s positions on many matters but create possible heartburn on others. That’s assuming, of course, he survives what could be a bruising fight to approve his nomination in the U.S. Senate.

Gorsuch is a strong admirer of the late Justice Antonin Scalia, whom he’s referred to as a “lion of the law” and whose seat Gorsuch would inherit, and most observers expect he would play a role on the court similar to the one Scalia occupied, emerging as a strong intellectual voice for a strict reading of the constitution. At just 49, Gorsuch would be positioned to sit on the Supreme Court for a long time, potentially decades.

Born in Denver but raised in Washington, Gorsuch has a stellar intellectual pedigree, featuring degrees from Colombia, Harvard and Oxford. (At Oxford he studied under Australian legal philosopher John Finnis, who converted to Catholicism in 1962, who has drawn on St. Thomas Aquinas in his work, who later became a member of the Vatican’s International Theological Commission and whose work there is believed to have influenced St. Pope John Paul II’s 1993 encyclical “Veritatis Splendor” on the importance of moral absolutes.)

Gorsuch serves as a federal judge on the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, and is based in Denver. His legal experience is extensive, including having clerked for Justices Byron White and Anthony Kennedy of the U.S. Supreme Court and having served as a high-ranking official in the Bush Justice Department.

From a Catholic point of view, Gorsuch’s strong support for religious freedom will strike many as attractive.

As a judge, Gorsuch sided with Christian employers and religious organizations in the cases of Burwell v. Hobby Lobby and Zubik v. Burwell, the main legal challenges to the Obama administration’s contraception mandates, with the latter involving the Little Sisters of the Poor and other Catholic groups.

In the Hobby Lobby case, Gorsuch wrote, “The Affordable Care Act’s mandate requires [such groups] to violate their religious faith by forcing them to lend an impermissible degree of assistance to conduct what their religion teaches to be gravely wrong.”

In a dissent in the 2007 case Summum v. Pleasant Grove City, Gorsuch found that displaying a religious monument, such as the Ten Commandments, did not obligate a governmental authority to display other offered monuments, such as those from other religions.

In Yellowbear v. Lampert in 2014, Gorsuch said that prison officials violated the religious rights of Andrew Yellowbear, who is of Native American descent, by preventing him access to the sweat lodge, which is critical to his faith.

In broad strokes, Gorsuch also seems opposed to the idea of using the courts to achieve social change that has not been accomplished through the political process.

For instance, he’s said that American liberals’ “overweening addiction” to using the courts for social debate is “bad for the nation and bad for the judiciary.” He cited three issues of direct Catholic interest as examples — gay marriage, school vouchers and assisted suicide.

In a 2006 book called “The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia,” he argued for “retaining the laws banning assisted suicide and euthanasia … based on the idea that all human beings are intrinsically valuable and the intentional taking of human life by private persons is always wrong.”

He also said that “to act intentionally against life is to suggest that its value rests only on its transient instrumental usefulness for other ends.”

Gorsuch has not been involved in any rulings that bear directly on the legal status of Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court decision legalizing abortion, but most observers regard him as fundamentally sympathetic to the pro-life argument.

Some pro-lifers have voiced concern that Gorsuch has cited rulings led by the late Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun, who supported the legality of abortion, has never used the phrase “unborn child” and has never explicitly spoken out in favor of the pro-life view.

However, Gorsuch did write in his 2006 book that the Supreme Court admitted that “no constitutional basis exists for preferring the mother’s liberty interests over the child’s life,” had the court considered unborn babies to be people.

Conservative commentator Ed Morrisey examined Gorsuch’s 2006 book and concluded, “Catholics would be very, very comfortable (and familiar) with Gorsuch’s reasoning on sanctity-of-life basis for equal treatment.” Michael Fragoso, a pro-life advocate and counsel to Senator Jeff Flake, R-Az., said that Gorsuch is as good of a judge as conservative and pro-life movements have ever seen.

Gorsuch also authored a strong dissent in the 2016 case of Planned Parenthood Association of Utah v. Herbert, in which a divided circuit court granted Planned Parenthood a temporary injunction after Utah Governor Gary Herbert directed state agencies to stop passing federal funds to the group following the release of videos depicting Planned Parenthood officials illegally selling fetal tissues and body parts.

On another front, given the growing emphasis on the environment in Catholic social teaching, the fact that Gorsuch upheld a set of renewable energy mandates in the state of Colorado, finding that they did not unduly burden out-of-state coal companies, may strike some Catholics as encouraging.

Yet Gorsuch is also known as a skeptic about over-reaching by government bureaucracy, in a way some critics see as hostile to the use of regulatory authority to defend not only environmental protections but also, for example, worker’s rights.

On the other hand, there are areas in which Gorsuch’s record may appear troubling from the point of view of Catholic social teaching.

For one thing, he’s generally rejected appeals from death row inmates seeking to avoid execution, and has favored a strict interpretation of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996. If he brings that approach to the Supreme Court, it would put him at odds with both the Vatican’s and the U.S. bishops’ call for abolition of capital punishment.

Catholics engaged in efforts to use legal pressures to compel corporations to act in socially responsible ways may also be concerned with Gorsuch’s history of protecting businesses from such challenges, including being critical of class action lawsuits by shareholders.

While practicing as an attorney, he wrote, “The free ride to fast riches enjoyed by securities class action attorneys in recent years appeared to hit a speed bump,” and that “securities fraud litigation imposes an enormous toll on the economy, affecting virtually every public corporation in America at one time or another and costing businesses billions of dollars in settlements every year.”

Gorsuch is also not generally seen as a strong advocate of immigrant rights, and last August joined an opinion ruling that Central American immigrants detained for being in U.S. illegally were not entitled to judicial review of their detention.

However, most observers doubt that Gorsuch would see his role primarily as pursuing an aggressive personal agenda on the court, since he’s a proponent of conservative legal philosophies that emphasize not going beyond the literal meaning of a statute.

In a 2005 speech at Case Western, he said judges should strive “to apply the law as it is, focusing backward, not forward, and looking to text, structure, and history to decide what a reasonable reader at the time of the events in question would have understood the law to be — not to decide cases based on their own moral convictions or the policy consequences they believe might serve society best.”

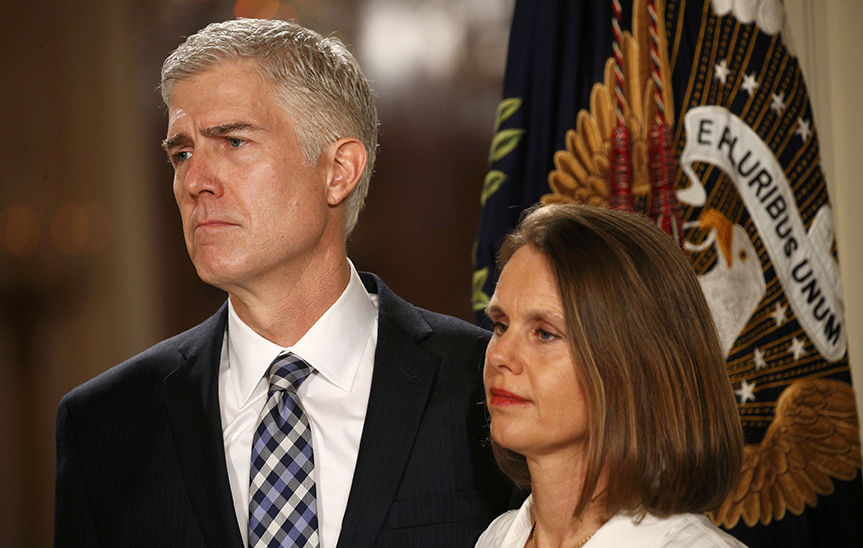

Gorsuch is also a product of Catholic education, having graduated from the prestigious Jesuit-run Georgetown Preparatory School in Washington, D.C., in 1985, where he won a national debate championship at the school. He’s said to be an avid fly fisher who enjoys being outdoors. With his wife, Louise, Gorsuch raises horses, chickens and goats, and often arranges ski trips with old friends and new associates from his former law firm.

Supreme Knight Carl Anderson of the Knights of Columbus voiced strong support for Gorsuch.

“We applaud the president’s nomination of Judge Neil Gorsuch to serve on the Supreme Court of the United States,” Anderson said. “From his writings and his record it is clear that he will interpret the Constitution as it was written, including our First Amendment right to religious freedom and the right to life of every person.

“It is hard to imagine a better, and more qualified, candidate,” Anderson said. “The Senate should swiftly confirm Judge Gorsuch to the Supreme Court.”

In accepting his nomination in a White House event Jan. 31, Gorsuch thanked his “friends, family and faith” as forces that keep him grounded.