Douglas Dodd, 75, has just published his first book: a memoir called “Our Father Who Art in an Iron Lung” (Atmosphere Press, $27.99).

Full disclosure: Douglas is an old friend from our University of New Hampshire days.

He was 6 years old when an ambulance pulled up to the family’s Andover, Massachusetts, home and took his father away to a hospital in Boston. Bruce Dodd had been stricken with bulbar paralytic polio: an especially pernicious form of the disease, usually fatal.

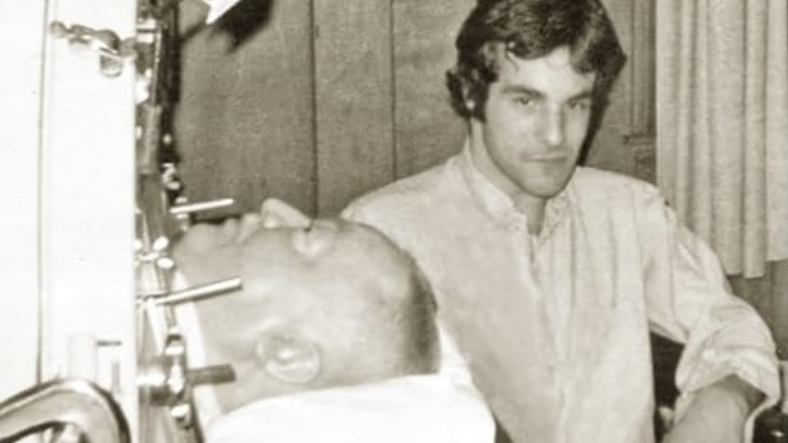

A Navy vet and MIT grad; a strapping, handsome production engineer of 34 — Bruce never walked, fed, or toileted himself, nor much moved again.

He lived for 21 more years, most of it in an iron lung, a cylindrical machine with a negative pressure ventilator that helps patients with paralyzed respiratory muscles to breathe.

In those days of early crisis, his mother (and later the children) would make innumerable visits to White 9: the polio ward of Boston’s Mass General Hospital.

Bruce’s friend Jim stopped by the house to tell Douglas: “You’re the man of the house now.”

And at six, he was.

His older sister Alison, 8, would bear the brunt then and in the coming years of taking care of the house and their two younger sisters.

But it was Douglas who learned to push the rotary lawn mower, relight the gas heater pilot, and shovel the driveways.

After Bruce came home from the hospital, a friend designed a 6-by-8-inch switch box that allowed him to turn on the lights, radio, and TV, buzz the kids, and use the telephone. A thick bundle of attached wires led to a big junction box in the cellar.

In one moving passage, the switch box needs repairing and Douglas, 10 by that time, tries to follow his father’s instructions and diagrams, running up and down the stairs, sweating, trembling, crying — but never in front of Bruce.

“I figured it out. I had to. I couldn’t say, ‘It’s too hard.’ Lesson? Nothing is that complicated if you can break it down into the smallest and simplest steps.”

Douglas’ mother, a remarkable woman in her own right, went to work as a realtor and would often be away from home. Bruce was the disciplinarian, the commander of respect, the keeper of order in the house, the guiding light.

From his prone position in the living room, he kept abreast of current events. By all accounts, he was a lively, witty conversationalist, a sympathetic listener, and a solid, steady personality who attracted all manner of people, young and old, to his bedside. “Can we hang out with your father for a while?” Douglas’s high school friends would ask.

He never dwelled in the past. He never complained. He never exhibited a shred of self-pity.

The Dodd kids were traumatized, each in his or her own way, but black humor also helped save them. They had acronyms: DWABP meant Daddy Wants a Bed Pan. Straining to turn Bruce’s inert bulk, they wondered how much an arm weighed, or a leg — he couldn’t use his appendages, anyway: What if they cut them off? Jokingly, the kids referred to him as Our Father Who Art in an Iron Lung.

The family wasn’t and isn’t particularly religious, but it’s not lost on Douglas that his father was a kind of Christ figure.

In a sense, he opines, his father willed himself to live, for the sake of his wife and children. Polio was a scourge in the mid-1950s. The Dodds had neighbors whose mother also developed polio and, perhaps sensing she wasn’t equal to the task of living with it, wasted away and died.

Bruce didn’t complain even after the 1965 appendectomy, the resultant stroke, and later — after the kids had left home for college, and his care became too burdensome — to the VA Hospital.

He never reproached, never guilt-tripped, never asked any of his children to change their plans for him.

And when he died, the neighbors came by the Dodd house for days to eat, drink, tell stories, and pay their respects. He was “a father confessor to half of Andover,” a family friend observed.

Douglas took the lessons he’d learned at his father’s side out to the world: “Someone has to do it,” for example — so Douglas did. An avid hiker, at 19 he was the hutmaster for Lakes of the Clouds in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, the largest hut in the Appalachian Mountain Club system.

He bought a rental property while still in college, more or less taught himself carpentry and contracting, and became a successful developer.

When a daughter, Eliza, was born with Down syndrome, he coached the local Special Olympic swim team for 19 years.

And when he decided, in semi-retirement, to write a book about his father, he did that, too.

He pays ample tribute to his three sisters: Alison, Carol, and Patty. But he never sentimentalizes the way the family responded, nor does he airbrush his own life. There were hard patches, guilt (if now largely worked through), raw memories: bankruptcy, a failed marriage, a period of too much drinking.

That honesty makes the story burn that much brighter. He never calls his father a hero because he so clearly was. And as we say in New England: “The fruit doesn’t fall far from the tree.”