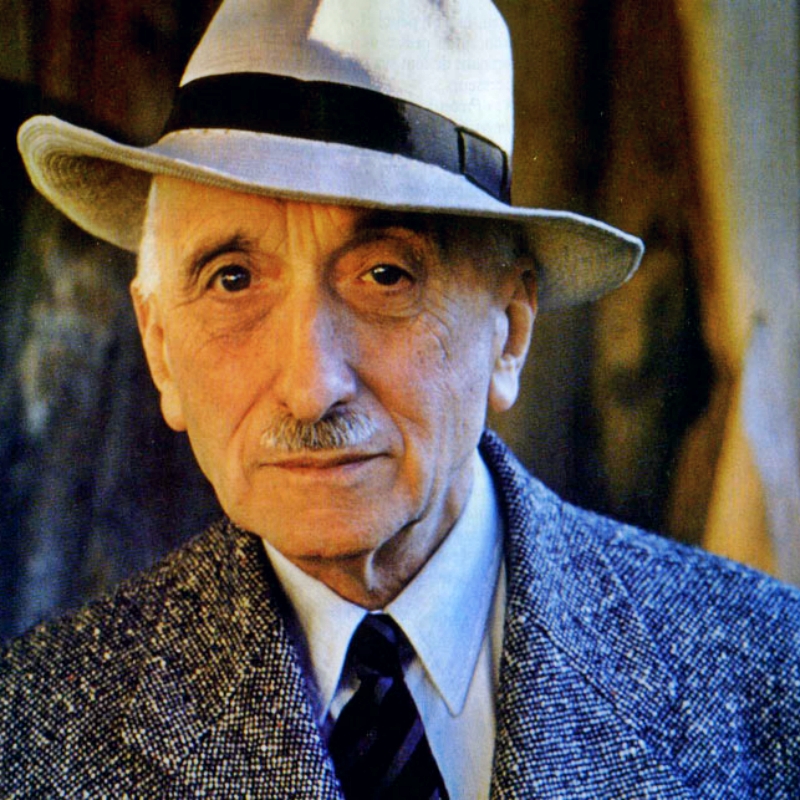

Elie Wiesel (1928-2016), survivor of the Nazi death camps, is best known for his 1960 memoir “Night” (Hill & Wang, $7.14)

With the recent surge of antisemitism, this monumental figure is well worth revisiting.

Terror had come slowly, then all too quickly, to the Hungarian village where Wiesel was raised. The Jewish community and his family had held him in a warm embrace. But after Passover in 1944, Jews were fenced off into ghettoes. Soon, more than 12,000 were herded off into transports. In April Wiesel, then 15, and his family boarded a transport themselves.

After a wretched journey, he watched his mother and little sister walk off to the crematorium at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

In the space of a day, he had his belongings and clothes taken away, his head shaved, and his body disinfected. Then he was made to stand in ill-fitting clothes in the freezing wind before men with snarling dogs, rifles, and clubs.

Already his central tragedy had occurred: he had lost his faith.

“The night had passed completely. The morning star shone in the sky. I too had become a different person. The student of Talmud, the child I was, had been consumed by the flames. All that was left was a shape that resembled me. My soul had been invaded — and devoured — by a black flame.”

On Rosh Hashanah, this formerly fervently observant teenage boy refused to celebrate with the others. “I was no longer able to lament. On the contrary, I felt very strong. I was the accuser, God the accused. My eyes had opened and I was alone, terribly alone in a world without God.”

The death of faith is the abiding theme of “Night.” (Lesser known are his two follow-up novels, “Dawn” (Hill & Wang, $10.60, 1961) and “Day” (Hill & Wang, $6.99, 1962), both of which also treat the problem of good and evil, survivor guilt, and loss of faith).

“Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire,” a 2024 documentary directed by Oren Rudavsky, amplifies the story of this remarkable man whose voice resounded across the globe. With extensive footage of his family, speaking career, and travels, the film’s aim is “to penetrate to the heart of the known and unknown Elie Wiesel: his passions, his conflicts and his legacy.”

Wiesel and his fellow prisoners were liberated from Buchenwald on April 11, 1945: his father had died there a few months before.

We learn that he made his way to France, was reunited with his two older sisters, studied at the Sorbonne, and became a journalist.

He spent the rest of his long life trying to keep the memory of his fellow Holocaust victims alive, urging humankind to speak out in the face of injustice, and reminding us that otherwise the seeds of evil may very well again take root.

“Night” evolved from an original manuscript of 862 pages that Wiesel completed in 1954. After several trimmings, a 116-page translation was published in 1960 by Hill & Wang.

“The act of writing is, for me, often nothing more than the secret of conscious desire to carve words on a tombstone, to the memory of all those I loved,” he observed, “and who before I could tell them I loved them, went away.”

In 1955 he made his way to America and spoke publicly about his experience. “Everything died in Auschwitz,” he told his listeners. “Ideals died there. Man died there. The image of God underwent a horrifying metamorphosis.”

In 1969 he married. Marion Wiesel, originally from Austria, translated many of his books from French to English.

The couple had one son, Shlomo Elisha Wiesel, named after Wiesel’s father. The family lived in Greenwich, Connecticut, and New York City.

Wiesel had not wanted to bring a child into the world but Marion convinced him. It was then that, in his wife’s words, “Elie became more religious. He had never stopped being religious. He uncovered it. It was like peeling off layers of nonreligion. And his true self emerged, which was religious.”

But his night and his suffering continued. Never could he forget his father, who with his dying breath in the camp had cried out for him, and who, in his own exhaustion and fear, he had been unable to console.

He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1985. In his acceptance speech, he said, “Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant.”

Wiesel’s earliest supporters were often Christian theologians, priests, and nuns, among them Catholic novelist François Mauriac — who wrote the Foreword to the 1958 version of “Night.”

“What did I say to [Wiesel]?” asks Mauriac, who was also given a Nobel Prize (in literature). “Did I speak to him of this other Jew, this crucified brother who perhaps resembled him and whose cross conquered the world?

“Did I explain to him that what had been a stumbling block for his faith had become a cornerstone for mine?

“If the Almighty is the Almighty, the last word for each of us belongs to Him. That is what I would have said to this Jewish child” — who is both all the children killed by the Nazis, and Wiesel himself.

“But all I could do was embrace him and weep.”