Servant of God Carmen Hernández, along with Kiko Argüello, co-initiated what is known as the Neocatechumenal Way.

The charism grew out of the Second Vatican Council, took root in Madrid and Rome, and has spread throughout the world in innumerable communities, attracting a multitude of catechumens.

The Way describes itself as “an itinerary of rediscovery of baptism and ongoing formation in the faith”; a proposition “to the faithful who wish to rekindle in their lives the richness of the Christian initiation” and live lives marked by humility, simplicity, and praise.

Meant to be lived in parishes and small communities comprising people from varying demographics, ages, and social groups, the aim is to gradually lead the faithful “to intimacy with Jesus Christ and transform them into active members in the Church and credible witnesses of the Good News. It is an instrument for the Christian initiation of adults preparing to receive baptism.”

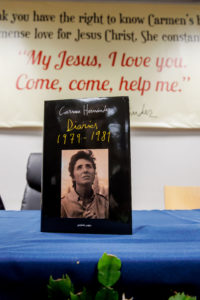

Hernández (1930-2016) left 30 years of diaries, which are being transcribed bit by bit. The first three years are now available: “Diaries: 1979-1981” (Gondolin Press, $24), with a foreword by Cardinal Séan O’Malley of Boston and a preface by Cardinal Ricardo Blásquez Pérez, archbishop emeritus of Valladolid, Spain.

As Blasquez notes, “Kiko was the catechist who always spoke and Carmen almost always listened, at times praying, at other times with restlessness and sometimes intervening with a pertinent reflection.”

Nonetheless, he says, we must assume that the development of the content of the catecheses, the “steps” and “rites,” and the organization of the evangelization was due to their combined work.

“Each one contributed the gifts received by God.”

Argüello (born 1939, still going strong at 85) is an extrovert who thrives in the limelight, an artist whose personality was especially difficult for Hernández. Her itinerant missionary lifestyle over 50 years required constant travel, crowds, and uprootedness. She never had a permanent place to lay her head, nor the silence and solitude that her contemplative spirit craved.

Her diaries are marked by an anguish that might be almost comical in its repetition, except for the genuine suffering that permeates almost every entry.

“I will fight against the ghosts of darkness. I will not dialogue with them, I will not let them rope me in. Away with you, Satan! The risen Lord… Gladden me Lord, fight at my side, invigorate and enliven my bones. Come, Lord. The Pope [John Paul II] is in Turin” (April 12-13, 1980).

“Nighttime crisis. Crisis on top of crisis. The stinginess of my heart. The pain of money, of life. My father. The impossible. Here, wildly spending unearned money. My Jesus, architects, lawyers, the languages, the Arabs…the deceit…My Jesus, to escape…where to? All your land seems like hell…” (Jerusalem, Feb. 11, 1981).

“Restlessness…itinerants, communities, pastors, Bishops. The Church, my Jesus, and the world, all is terror, terrorism, terror, terror, powerlessness, impossibility, distrust. My Jesus, my Jesus, if I had faith in You, if my feet were on your holy rock… But I don’t see your face, I don’t see anything, I suffer, I suffer, and I suffer in the helplessness of death and in a visceral silence. My Jesus, I lament… I cry out to You, answer me. Have mercy on me in this unbelief of death” (Rome, May 21, 1981).

“The mystery of suffering and grief. People overwhelm me. I want to escape. Kiko terrifies me with his crazy prayers. My Jesus, the mountains: ghosts of the Gran Madre di Dio, the accusations…

“Finally, peace. Incredible freedom…My Jesus, sweet company. These things that St. Teresa speaks about, we have sweetly lived for so many years. Come, accompany me. I love you. Say it to me. Come, Jesus” (Rome, May 31, 1981).

During the next several months, she suffers insomnia, dentist crises, hospital stays, dissatisfaction, “groggy from smoking, fighting, yelling, my Jesus.” Darkness, terrible thoughts, sadnesses, the terror, the trial.

Occasionally, she enjoys a brief reprieve: “Blessed are you. I am in grace” (Madrid, Oct. 27, 1981).

Then, once again, she’s plunged into darkness: “I’m dead tired. Kiko is impossible. Help me, Jesus” (Madrid, Dec. 5, 1981).

The odd-couple pairing brings to mind Servant of God Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin who, together and in spite of very different sensibilities, founded the lay Catholic Worker movement.

These platonic friendship-collaborations, it seems, each resembling an incredibly difficult marriage, bore fruit only because both partners — from love of God — stuck it out till the end.

I have no personal experience of the Neocatechumenal Way. Like most lay movements, it has its passionate adherents and its detractors.

But the Lord works in mysterious ways, his wonders to perform. That the Way grew out of such agony, on Hernández’s part; that in a way it should not have worked, but did — is perhaps the real takeaway.

And let’s not forget, there are 27 more years of diaries to come!

In the meantime, what struggling human being can’t relate?

“Vatican. My Jesus, Fr. Maximino, itinerants, nothing consoles me. Nausea, terror, fear. My Jesus, where can I escape? Serenity.

“Firenze [Florence, Italy]. My Jesus, it’s incredible that on the same day one can feel so differently about things, from fear to serenity, from difficulty to indifference. My Jesus, how mysterious the human psyche is. Help me” (Rome, May 27, 1981).