Artist Anne-Elizabeth Sobieski’s family lost their Pasadena home to fire when she was 17. “I was frozen. I don’t know how much time went by. We just watched as the roof fell in, and one by one, every room burned.”

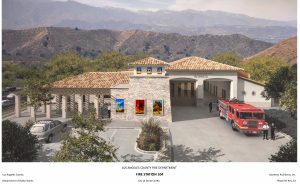

Ever since, she’s had a special heart for firefighters. So perhaps it was only fitting that she was chosen by the LA County Department of Arts and Culture (formerly the LA County Arts Commission) to design the fused glass panels for the newly built Santa Clarita Fire Station 104.

“The county’s awarding of public art projects is really an outreach to the community, which I think is the most beautiful thing in the world. They provide arts education programs, fund teachers and individual artists, work with the incarcerated, give apprenticeship grants, and much more. They invite people like me who have never done a public project before.”

From the beginning, she had to consider how she needed to design the panels so they’d look well in glass. Judson Studios, based in Highland Park, is the oldest family-run stained-glass studio in America. She hired them to team up on the proposal and to fabricate the panels.

Her initial proposal focused on the landscape, the history of Santa Clarita, and the community for whom fire tends to be traumatizing.

So the initial proposal didn’t include depictions of actual fire. The firefighters immediately asked, “Where’s the fire?”

She made a conscious choice to spend more time with them. That was when the project really came together.

She learned that the fire chiefs and captains also do payroll, cook, and clean. They comprise a team and a culture. She went on-site, and tagged along for a day. She saw the faces of the students when firefighters arrived to help a collapsed teacher.

“The firefighters are always in action, on the move, solving problems. Something like 80% of their calls are medical. But though they don’t want anyone to get hurt, they do love to fight fire. Their favorite thing is a fire that has no structures and no people. Almost every one of them has a screensaver that depicts a firefighting scene.”

So she brought in fire. Every detail and element had to be hammered out. The process consists first of drawings, then color comps, then painting the drawing on the glass.

The fabricator arranges the glass on top of the drawing, using cut glass and frit on the edging, so that the colored glass can melt together and is more painterly. Then it goes into the kiln. “Tim Carey, the main fabricator, ended up doing an incredible job.”

The three main panels are on the front of the building. Installed side by side into the actual glass, they act as the structure’s “windows.”

They evoke the project’s watchwords: “Strength, Camaraderie, and Service.” The first depicts an anonymous firefighter in a yellow coat, training a hose on a blazing fire. The second is a tree, backlit by fire. The third features a firefighting helicopter, battling a conflagration below.

Standing before them, the viewer is struck by the bright yellow coat, instantly recognizable to a child. The heart-racing red of a wind-whipped fire. The ominous midnight blue of a night sky as below men and women toil and lives are at stake. The sense is of urgency, danger, action, and the majesty of all in this world that is out of our control.

The “front” of the three panels faces inside so the firefighters get to enjoy the translucent “candy” surface. Light infuses the windows during the day, so the effect is the same as stained glass would be in a church.

At night, the windows are illuminated from within so the images reflect out to the community.

“The idea was that for people driving by, the fire station is like a lighthouse, a beacon of safety. They see the images of the firefighters in action and the Santa Clarita sunset. They’re going home for the day, theoretically to rest, and the firefighters are on watch, keeping guard over the community.”

The number of the firefighters’ station, 104, is a big point of pride. With each numeral fused into a separate glass panel, the number appears on two adjacent sides of the station’s elevated tower. From the outside during the day, the eyes of a passerby would be drawn to these as their white opaque backing reflects the sunlight.

But the firefighters’ favorite turned out to be the night scene in the dayroom. Because the shades are often drawn during the day so that they can teach using TV monitors, the panel, depicting a raging fire that goes all the way across with no structures and no people, is displayed to full effect.

“I do feel my strength on the project is that I became deeply invested in the firefighters’ experience. They’re passionate about what they do. So they really appreciated that we double, triple, quadruple checked the details: the color of the hose, the gloves, the helmet, the gear bags.”

The collaboration among her project manager, Judson, and the whole team was to Sobieski the most important part of the project. “The concept of service that underlies the firefighters’ work ended up coming full circle. So it’s been incredibly meaningful, a huge learning curve, and a real grace.”