First published in 1922, Margery Williams’ “The Velveteen Rabbit: How Toys Become Real” is one of the most beloved children’s books of the 20th century. The story is also very much one of death and resurrection.

The book begins:

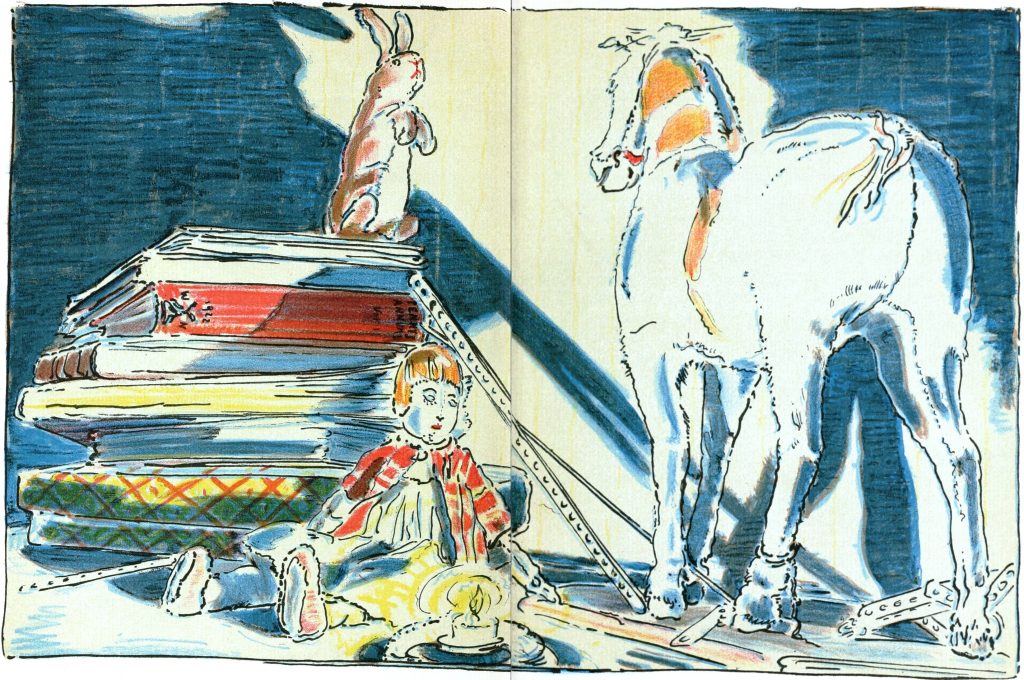

“There was once a velveteen rabbit, and in the beginning he was really splendid. He was fat and bunchy, as a rabbit should be; his coat was spotted brown and white, he had real thread whiskers, and his ears were lined with pink sateen. On Christmas morning, when he sat wedged in the top of the Boy’s stocking, with a sprig of holly between his paws, the effect was charming.”

The Boy loves him, “for at least two hours,” but there are many other toys that morning and what with “a great rustling of tissue paper,” and the excitement, and a lavish family dinner, the Boy forgets all about the Velveteen Rabbit who for a long time lives in the toy cupboard or on the nursery floor.

The Rabbit is “naturally shy” (read: humble) and while mingling with the other nursery inhabitants, learns the ways of the world: that the more modern, mechanical toys look down on him, that the strong dominate the meek, that in such company he is made to feel “very insignificant and commonplace.”

But “nursery magic is very strange and wonderful, and only those playthings that are old and wise and experienced like the Skin Horse understand all about it.”

The Skin Horse, who is bald in patches and whose tail hairs have been pulled out to string bead necklaces, alone among the other toys is kind to the Velveteen Rabbit.

“What is REAL?” asked the Rabbit one day, when they were lying side by side near the nursery fender, before Nana came to tidy the room. “Does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?”

“Real isn’t how you are made,” said the Skin Horse. “It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real.”

“Does it hurt?” asked the Rabbit.

“Sometimes,” said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. “When you are Real you don’t mind being hurt. … It doesn’t happen all at once. … You become. It takes a long time. … Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don’t matter at all, because once you are Real you can’t be ugly, except to people who don’t understand.”

One person who doesn’t is Nana, a stand-in for all those who favor efficiency, hygiene, and “tidying-up” over fun. For his own part, languishing in the cupboard, the Rabbit longs to become Real but, like us, would just as soon forgo the discomfort involved.

But one night as Nana hurriedly puts the Boy to bed, she looks around in vain for the china dogs, swoops into the toy cupboard and, dragging out the Rabbit by one ear, puts him in the boy’s arms. “Here,” she says, “take your old Bunny! He’ll do to sleep with you!”

The Boy holds the Rabbit to his breast, makes tunnels for him under the blankets, and eventually refuses to let him out of his sight. So happy and secure is the Rabbit in the Boy’s love that he doesn’t even notice that his fur is falling out, his tail is becoming unsewn, and the pink has rubbed off his nose where the Boy has kissed him.

One dreadful night the Boy becomes sick. Scarlet fever tears through the nursery. Though he recovers, the doctor orders that all the infected toys be burned. Peeking forlornly out of a sack at the end of the garden, the Rabbit asks himself the question that at one time or another burns deep within every human heart: “Of what use is it to be loved and lose one’s beauty and become Real if it all ended like this?”

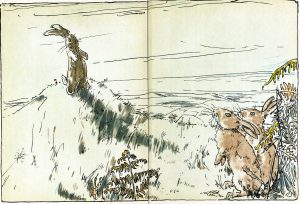

A tear falls down his cheek. Out of it grows a mysterious flower. And from the flower steps the nursery magic Fairy. When the toys are old and worn out and the children don’t need them anymore, the Fairy explains, she takes them away with her and turns them into Real.

And so it comes to pass: the Rabbit is incarnated. Just as the disciples didn’t recognize Christ after the resurrection, the Boy doesn’t quite recognize the Rabbit when he appears in the garden after becoming Real.

Also unstated is the fact that now that the rabbit has taken on flesh and blood, he will eventually die.

Then again, love — Real love — is eternal. That’s the message that, augmented by William Nicholson’s beloved color illustrations, have made “The Velveteen Rabbit” a book for the ages.

In fact, the wise old Skin Horse might have been gazing out the nursery window toward the Christmas star when he imparted this miraculous news:

“Once you are Real you can’t become unreal again. It lasts for always.”