Sir Alec Guinness (1914-2000), renowned British actor, converted to Catholicism after playing a priest in the 1954 film “The Detective,” aka Father Brown.

Perhaps best known for his role as the bearded sage Obi-Wan Kenobi in the “Star Wars” films, Guinness was born into a broken family. His mother, Agnes Cuffe, was unmarried. He never knew his father. Abused by a brutal stepfather, as an adolescent Guinness discovered the solace of the theater. Confirmed into the Anglican church at 16, as a youth he dabbled in various religions while secretly considering himself an atheist.

Religion, he believed, was “so much rubbish, a wicked scheme of the Establishment to keep the working man in his place.”

Acclaimed for his role of Hamlet on the London stage, he went on to launch what would prove to be an equally illustrious film career: “Oliver Twist” (1948), “Kind Hearts and Coronets” (1949), “The Man in the White Suit” (1951).

In 1954, he was cast as the lead in “The Detective,” a film based on the character of G.K. Chesterton’s crime-solving priest, Father Brown. On location in France, he was walking down the street one evening, still clad in his stage vestments, when a local child mistook him for a real priest, trustingly took Guinness’ hand, and began accompanying him down the street.

In “Blessings in Disguise,” the first volume of his autobiography, he wrote of the incident:

“Continuing my walk I reflected that a Church which could inspire such confidence in a child, making its priests, even when unknown, so easily approachable could not be as scheming or as creepy as so often made out. I began to shake off my long-taught, long-absorbed prejudices.”

Just before filming began, the actor’s son Matthew, 11, had contracted polio. Guinness began ducking into “a rather tawdry little” local Catholic church to pray. He made a bargain with God: if Matthew were healed, he wouldn’t object should the boy ever express a desire to convert to Catholicism.

Matthew did recover. Guinness, his wife, and his son all converted to Catholicism.

“There had been no emotional upheaval,” he wrote, “no great insight, certainly no proper grasp of theological issues; just a sense of history and the fittingness of things.”

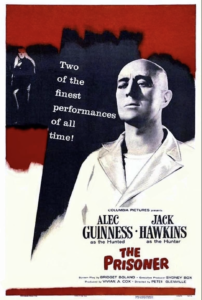

Guinness played a priest in another, lesser-known film, “The Prisoner” (1955).

Adapted from a play by Bridget Boland and directed by Peter Glenville, the film considers such contemporary issues as public shaming, the surveillance state, and anti-Church sentiment.

The story is set in the early years following World War II, in an unnamed country under totalitarian rule. In one scene, a child is shot in the back for painting the words “Free Speech” on a wall. A little heavy-handed, but we get it.

A long-suffering but conscientious cardinal — slightly enamored of his reputation as a popular hero after having survived torture by the Nazis — has been arrested for treason.

His interrogator, played by the formidable Jack Hawkins, is a former Resistance comrade of the cardinal’s who, for reasons unknown, has switched his allegiance. He knows that physical force will be of no avail against the ascetic priest’s unswerving will.

“You represent a religion which provides an organization outside the state,” he announces at the outset. “You’re a national monument and that monument must be destroyed, defaced.”

“I’m difficult to trap and impossible to persuade,” the cardinal responds.

An agonizing, monthslong, cat-and-mouse game ensues, designed to break the prisoner psychologically and spiritually.

Later, weakened, the cardinal will muse, “Surely it’s a confession you want, not the truth.”

After weeks of forced insomnia, he reveals a devastating childhood wound and “confesses” to a sin of which he may or may not be guilty.

Exposed to his flock as an ostensible fraud, the prisoner has served his purpose. Poised for release, he tells a guard, “Try not to judge the priesthood … by a priest.”

The film raises issues that are at least as relevant now as they were 70 years ago. The cardinal’s “confession,” forced by fear, isn’t all that different from today’s groveling public apologies for having stated a truth, or merely an opinion, that goes against the reigning groupthink.

In another way, though, you could say that the cardinal’s faith has healed him. The confession was forced but neither was it entirely off the mark. Under torture and duress he has undergone a dark night of the soul that, in spite of his adversary’s malign motives, has been inadvertently cleansing — and that may also have inadvertently converted his interrogator.

Clad once more in his vestments, he parts the waiting crowd, leaving the viewer to wonder whether he will be accepted or shunned by his people, and leaving us to wonder as well: which of the two adversaries is the real prisoner?

Guinness was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1959 for services to the arts.

He died of liver cancer in 2000. His wife passed away two months later. The two had been married 60 years.

Watching Guinness now, it’s lovely to contemplate the source from which his devotion to family and to his acting vocation sprang.

He once described walking a London street when, with joy in his heart, he began running. “I ran until I reached the little Catholic church there ... which I had never entered before; I knelt; caught my breath, and for 10 minutes was lost to the world.”