For the month of May, my media ministry Word on Fire offered a challenge: pray 50,000 Rosaries on behalf of those who have fallen away from the Church. The invitation went out to the whole world, and the response was fantastic. More than 90,000 Rosaries were prayed. For the month of July, Word on Fire asked for 10,000 Holy Hours to be prayed for the success of the National Eucharistic Revival. As I compose these words—about a third of the way through July—already 5,000 have been offered.

The Holy Hour is a practice closely associated with the great Archbishop Fulton Sheen. At the close of every talk Sheen ever gave to priests, he challenged his brothers to spend, every day, an hour of uninterrupted prayer in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament. Though the Holy Hour was not emphasized when my generation was going through the seminary, it has been enthusiastically embraced by the present generation of seminarians and young priests—and through them, it has begun to have a powerful effect on the entire Church. In three very different dioceses—Chicago, Los Angeles, and now Winona-Rochester—I have seen parishes completely revolutionized by the practice of sustained Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament.

Some have put forward a criticism of Word on Fire’s campaigns: Do you really think that God will be persuaded by the sheer number of prayers and Rosaries offered? Well, that’s just missing the point. The purpose of the campaign is not so much to influence God as to encourage people to pray, to raise their minds and hearts to God. And this, as I have been arguing for years, is of prime importance today when a soul-killing secularism has gripped so many in the West, especially young people. These slower days of summer provide a greater opportunity to pray, to rest in the Lord, to consider the higher and deeper things.

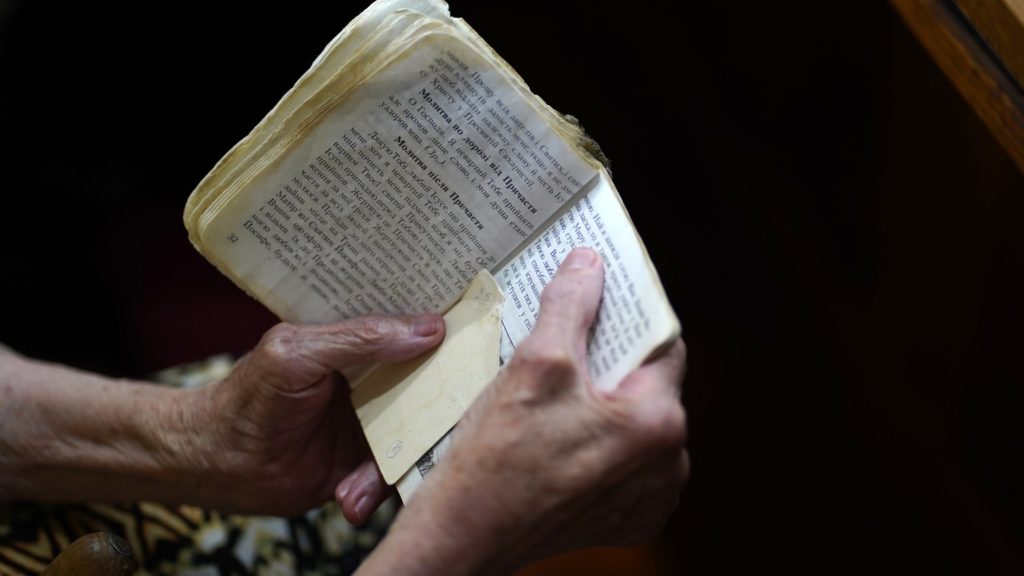

I have already referenced two practices of prayer, but may I recommend some others, especially if you have been away from prayer for a while? First, pray with the Scriptures, using what the spiritual tradition calls lectio divina. There is no text more central, more sacred, more inspired than the Bible itself. In his First Letter to Timothy, St. Paul refers to the Bible as theopneustos, literally, “God-breathed.” He means that the Holy Spirit (a term that means “Sacred Breath”) blows through its words, its images, its narratives. Therefore, if you want to get in touch with that Spirit, open the Bible. But approach it, not casually, but in a spiritually disciplined way. Lectio divina (divine reading) is a four-step method. First, you read a scriptural passage slowly and with great attention. This is called “lectio.” Next, you “chew” on the text, mulling it over, allowing its images and ideas to soak into your own spirit. This is called “meditatio.” Third, having heard the word, you speak back to God; you tell him how the text has affected you. This is called “oratio.” Finally, having spoken to God, you listen deeply to what he says back to you. This highest engagement with the Bible is termed “contemplatio.” Try this method during these summer months, making sure you choose a relatively short passage from the Bible.

A second method I would suggest is what the tradition calls “centering prayer.” Find a quiet place, compose yourself, fix your gaze on an image of the Lord or on a crucifix. Then, imagine all of the elements of your life—your friendships, your job, your kids, what you do for recreation, your political commitments, etc.—and consciously place them in relation to Jesus. Perhaps you could imagine a rose window in which all of the various features of the design are connected by spokes to the center. In the presence of God, honestly assess to what degree the various aspects of your life are under the Lordship of Jesus, truly connected to him. The great spiritual masters teach us that the steady practice of this prayer actually brings about the unity and harmony that you seek. Many years ago, a young man approached me, and without telling me much about himself, simply asked for recommendations as to how to pray. I gave a basic instruction in centering prayer. About a month later, he returned and said, simply enough, “I have to stop having promiscuous sex!” I knew nothing about his sex life and had given him no advice; the prayer itself had brought a key aspect of his life online.

A final suggestion I offer especially to those who have no strong relationship to church or liturgy or the tradition of prayer. Use nature itself as a prompt to pray. Great saints—Francis of Assisi, John Paul II, Pier Giorgio Frassati come readily to mind—loved to commune with God amidst the glories of the natural world. Frassati was a mountain climber (hence his spiritual motto, Verso l’alto, “to the heights”); John Paul loved to ski in the mountains of Poland and Italy; and Francis moved with enthusiasm through field and forest, going so far as to preach to the birds! Thomas Aquinas taught that whatever exists is marked by goodness, truth, and beauty. So go out into the natural world. Maybe you’re closest to the sea or the desert or a forest or a lake—it doesn’t matter. Move into that space and wonder at the splendor, intelligibility, and value that you see. And then ask a very simple question: Where did all of that come from? In posing that question, you are at the threshold of prayer.

So might I urge everyone, during these more languid weeks of summer, take the time to pray!