It really doesn’t matter that the television series I am currently binging is more than six years old. The plethora of content and expanding streaming platforms makes the old new again for a lot of viewers like me who were either too cheap or too busy to catch a show when it was on a subscription service the first time around.

It also doesn’t matter that this particular show is “ancient” in popular culture years, because its subject matter is something American movie-going and television-watching audiences have been infatuated with since those first fuzzy black and white images flickered onto the screen of a nickelodeon: bad guys.

The show is “Narcos,” and it is divided into two three-season arcs. One arc is about how the Mexican drug cartels came into existence. The other arc is about the rise and fall of the most notorious Colombian drug dealer of them all, Pablo Escobar. The series’ disclaimer states that even though some of the characters are fictitious, and some businesses and names changed, the stories are based on facts. To that I can say, with mouth agape, that if half of these facts are indeed facts, the global drug trade is its own circle of hell.

The cast and writing are about as good as it gets, though the series is grotesquely violent and has more gratuitous “adult” content than it needs to have. And although the bad guys — and they are very bad — are compelling, at no time did I feel the makers of the series were trying to show the warmer and fuzzier side of drug lords.

It is almost refreshing to have a series with protagonists I could root for. They may not be perfect characters — some of them are seriously flawed — but these good guys all have a foundation of decency that also taps into an era gone by.

Fascination with the portrayal of evil goes back to the Garden of Eden. A slightly less ancient popular culture example, which helped give birth to shows like “Narcos,” was the American gangster film of the early part of the last century.

It was a bold and economically dangerous decision in 1931 when Warner Brothers cast James Cagney in one of the earliest gangster movies, “Public Enemy.” The shocking part was that community standards then insisted that the lead should be the police officer or the crusading lawyer, not the bad guy.

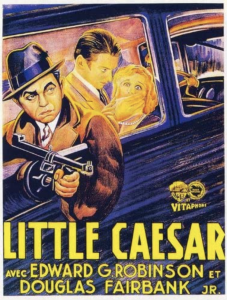

The movie was a huge hit and others like it changed the landscape in Hollywood for decades. Films like “Little Caesar,” “Scarface,” and “Angels with Dirty Faces” all had homicidal criminals as their lead characters.

In the post-World War II world, when the “greatest generation” realized the world was a lot more complicated than they had been told, bad guys in movies changed again. They became more sympathetic. In some cases, bad guys in movies were portrayed as preferable to the “good guys,” who oftentimes were more corrupt than the “official” evildoer.

When the cultural and sexual revolution hit in the 1960s, things went into overdrive. Warren Beatty’s seminal ’60s film portrayed Bonnie and Clyde — real-life cold-blooded killers — as folk heroes striking a blow against the establishment and standing up for the little guy. Beatty chose to ignore the fact that the real Bonnie and Clyde had no problem mowing down dozens of “little people” with Tommy guns and Browning automatic rifles as they robbed and murdered their way across the country.

The modern “Narcos” series is a throwback to earlier times. The self-absorbed, pathological megalomania of drug kingpin Pablo Escobar is a newer version of Edward G Robinson’s Little Caesar almost a century before. And the suave and sophisticated Mexican drug king Miguel Angel Felix Gallardo is reminiscent of the descent into evil we watched happen to Michael Corleone in the “Godfather” saga of the 1970s.

Why do these stories about despicable people enthrall us so? It probably has something to do with original sin. Pablo Escobar was probably no more self-absorbed with himself than Adam and Eve were. Escobar was worth an estimated $25 billion, but it was never enough. Adam and Eve had everything they ever needed, and yet they wanted more.

Although most of us are not multi billionaire drug kingpins, we all have something to answer for, and a day of reckoning on our horizons. If stories about bad guys help us keep our own faults and coming judgment in mind, they serve us well.