ROME — Last week the Archdiocese of Munich in Germany released a comprehensive, almost 2,000-page report on sexual abuse, the central finding of which was that almost 500 victims suffered abuse at the hands of Munich priests over a 74-year period.

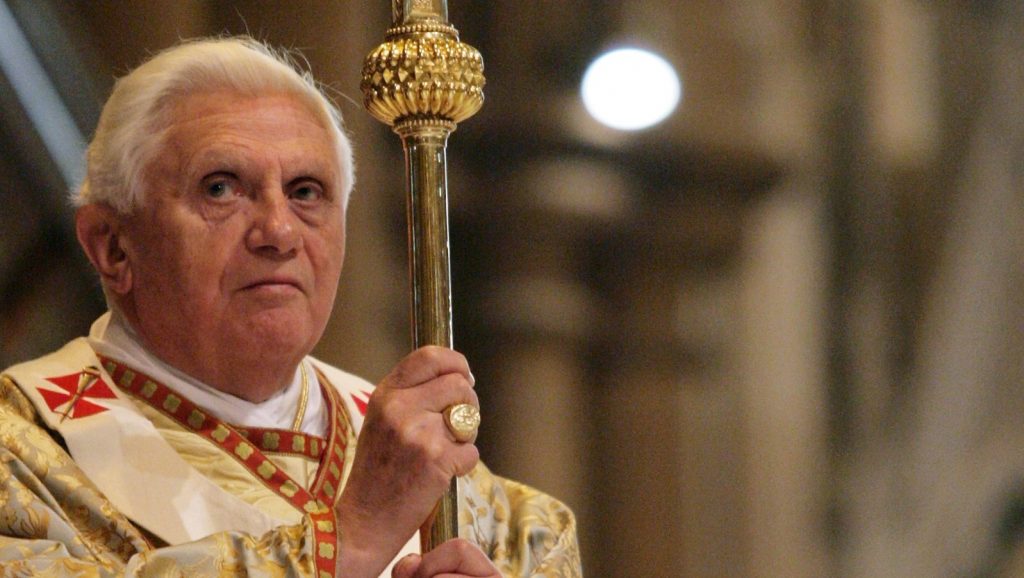

Inevitably, however, most media attention has concentrated on just five of those 74 years: The period from 1977 to 1982 when the archdiocese was led by Archbishop Joseph Ratzinger, later made a cardinal, who would go on to become Pope Benedict XVI.

Headlines around the world proclaimed that the report faults Archbishop Ratzinger for his handling of four cases of sexual abuse during his five-year term, and much commentary has suggested that the findings will taint his legacy. America’s leading advocacy group on behalf of clerical abuse victims, the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests (SNAP), called on him to relinquish his status as pope emeritus.

As part of the fallout, an aide to Pope Benedict has been forced to acknowledge that the emeritus pontiff erred in claiming in responses to researchers for the report that he had not attended a 1980 meeting in which the case of one abuser priest was discussed. The aide blamed the misstatement on an “editing error.”

While Pope Benedict has said he’s studying the full report before issuing a statement, the Vatican came to his defense with an article by Editorial Director Andrea Tornielli insisting that his aggressive reforms to combat child abuse during his eight years as pope “can neither be forgotten nor erased.”

The current archbishop of Munich, Cardinal Reinhard Marx, was also faulted over his handling of two cases in the report. Cardinal Marx made headlines last year when he offered his resignation to Pope Francis over the German church’s abuse scandal. In remarks to the media after the new report’s release, Cardinal Marx reiterated his apologies to abuse victims, saying he bore “moral responsibility” for their suffering.

To understand the furor over the Munich report and its implications for Pope Benedict, it’s important to make four basic observations.

First, the future pontiff led the Munich archdiocese during a period when the Catholic Church’s overall response to claims of child sexual abuse was woefully inadequate, as everyone in leadership today would acknowledge. Given the size of the Munich archdiocese and the broad patterns in place at the time, it would be surprising if there were no cases of abuse during any randomly selected five-year period from 40 years ago.

In that sense, even if it were to be demonstrated that Pope Benedict was somehow culpable for actions taken as head of the archdiocese, it would do no more than confirm what we already knew about the lethargy and indifference of Church leadership in that era.

Second, the number of cases in which Pope Benedict’s conduct is in question is actually three, not four, because in one instance the authors of the report themselves end up clearing him. They concluded there’s no factual basis for assuming he had any knowledge of the abuse.

“Against this background, [the experts] no longer see any reliable basis for continuing to proceed from the knowledge initially assumed and for critically assessing the actions of the then Archbishop Cardinal Ratzinger in this case, as was done in the context of the preliminary assessment. Rather, they see him as exonerated overall,” the report said.

Third, none of the four cases cited in the Munich report actually involve sexual abuse of a minor that occurred on the future pope’s watch.

Two regard instances in which priests who were accused of sexual abuse outside the archdiocese were allowed to relocate to Munich without restrictive measures being imposed, while the other two involve offenses that didn’t rise to the level of abuse — specifically, swimming naked in a river and taking photos of minor girls getting dressed for a theater play.

In those two instances, the future pope actually did take action. With the priest who was observed swimming naked, he was removed from the parish in which he was serving and eventually sent home; the priest caught taking pictures of girls was removed and assigned to a hospital and home for the elderly, with the stipulation he was to have no contact with minors.

While those actions might be seen as insufficient by today’s standards, they were consistent with general Church patterns for what was considered responsible leadership at the time. In any event, neither demonstrate that the future pope mishandled “abuse,” because there was no actual sexual abuse involved.

Fourth, given that the facts produced in the report regarding Pope Benedict can be interpreted in different ways, there’s a danger that reactions going forward will break down along largely political lines, with conservatives rushing to Pope Benedict’s defense and liberals inclined to accept the indictment — in both cases, for reasons that have little to do with a careful reading of the evidence.

Conservative German Catholic journalist and historian Michael Hesemann, for example, summed up his take this way in an interview with Deborah Castellano Lubov of Exaudi.

“There are circles in Germany who want a different Church, an anthropocentric Church, more protestant, more ‘open to the world,’ Hesemann said. “For them, Pope Benedict is a symbol, a symbol for the ‘old’ theocentric Church. This is why they try everything to slander him, to discredit him and everything he taught us as theologian, bishop, cardinal, Prefect of the CDF and Pope. … For them, he’s the perfect scapegoat.”

In that sense, it’s possible that reaction to the Munich report, at least right now, may not tell us as much about Pope Benedict’s history as it does about our own present, and the way in which ideological fault lines end up distorting angles of vision on just about everything.