Brian Doyle (1956–2017) wrote essays, short stories, memoirs, novels, and prose-poem hybrids he called “proems.” His work appeared in “Harper’s,” “Orion,” “The Sun” magazine and, repeatedly, in the “Best American Essays” series.

He won three Pushcart Prizes, was widely anthologized and, after being nominated nine times for the Oregon Book Award, won in 2016 for his novel “Martin Marten.”

He edited “Portland,” the magazine of the University of Portland, for more than 25 years, attracting such top-tier writers as Annie Dillard, Pico Iyer, Scott Russell Sanders, and Kathleen Norris. Under his leadership, the publication was consistently ranked among the best university magazines in the country. He’s been called “superhumanly prolific.”

He was also a husband, father of three, and apparently mentor to hundreds.

In November of 2016 he was diagnosed with cancer and underwent surgery for what he referred to as “a big honkin' brain tumor.”

He died in May the next year.

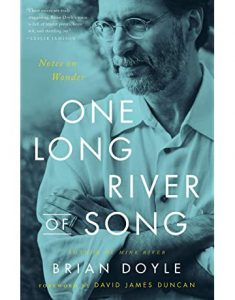

“One Long River of Song” (Little, Brown and Company, $18) is a posthumous essay collection. In the foreword, fellow writer and longtime friend David J. Duncan notes that “for a Catholic writer to have his work chosen for ‘Best American Essays’ by [nature poet/mystic] Mary Oliver and by the famous atheist Christopher Hitchens bespeaks [Doyle’s] extreme range of appeal.”

To call Doyle’s style exuberant would be an understatement. He doesn’t tell stories so much as riff, energetically meander, explode. He turns verbal somersaults, gleefully alliterates, prankishly puns.

He loads on adjectives: “extraordinary ordinary succinct ancient naked stunning perfect simple ferocious love”; “the glorious hilarious epic sprawling wondrous novel ‘The Horse’s Mouth,’ by the Irishman Joyce Cary.”

He redeems the much-maligned run-on sentence. “[T]o exhaustion I say yes, and to the puzzling wonder of my wife’s love I say O yes, and to horror and fear and jangled joys I say yes, to my absolute surprise and with unbidden tears I say yes yes O yes.” That’s from the essay entitled — what else? — “Yes.”

From “His Last Game”: “We drove around the edges of the college where he had worked and we saw a blue heron in a field of stubble, which is not something you see every day, and we stopped for a while to see if the heron was fishing for mice or snakes, on which we bet a dollar, me taking mice and him taking snakes, but the heron glared at us and refused to work under scrutiny, so we drove on.”

He writes of praying by the bedside of his infant son, one of a pair of twin boys, who was born with a faulty heart; of heroic female teachers; of the pain, unspoken for 70 years, of his father’s childhood.

He writes pieces entitled “The Wonder of the Look on Her Face,” “His Weirdness,” and “20 Things the Dog Ate.”

I once submitted an essay to “Portland” that had languished at another magazine for nine months. Doyle responded with an acceptance within three hours.

He responded within hours other times with a rejection. But any writer will tell you, to know one way or another, within a reasonable amount of time, whether a magazine or literary journal wants your piece is a rare and precious gift.

He had a heart for humanity. He saw the glory of God in everyday things: a talk with a friend, a kid’s smile, the maddening mystery of marriage, a good joke.

I wonder if that kind of eye and ear, ever poised to get a kick out of life, doesn’t do more to spread the Gospel to the ends of the earth than any number of mummified homilies.

His essay “Leap” may be the best thing ever written in the aftermath of 9/11.

Bystanders that day reported seeing people falling, jumping, leaping from the Twin Towers in an effort to escape the flames.

Several people observed a couple leaping, hand in hand. Were they married? Boyfriend and girlfriend? Colleagues? Strangers? We’ll never know. We do know this:

“But he reached for her hand and she reached for his hand and they leaped out the window holding hands. … Their hands reaching and joining are the most powerful prayer I can imagine, the most eloquent, the most graceful. It is everything that we are capable of against horror and loss and death. It is what makes me believe that we are not craven fools and charlatans to believe in God, to believe that human beings have greatness and holiness within them like seeds that open only under great fires, to believe that some unimaginable essence of who we are persists past the dissolution of what we were, to believe against such evil hourly evidence that love is why we are here.”

“You want to help me?” Doyle said as death drew near. “Be tender and laugh.”