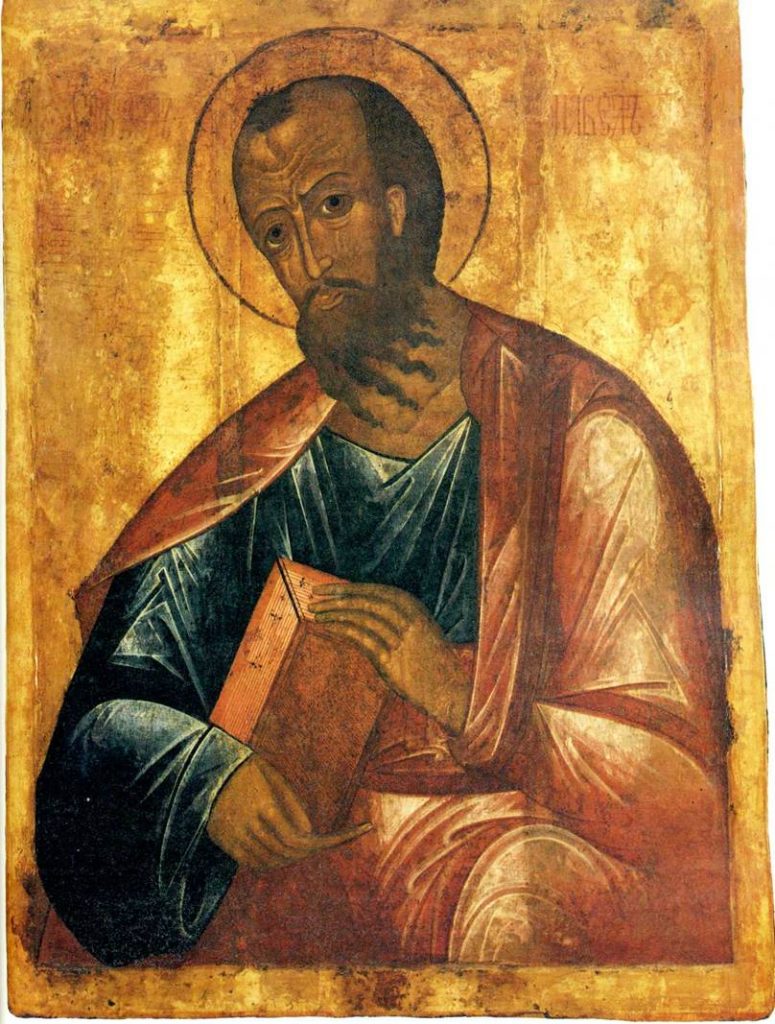

Another in a series about St. Paul.

Saul the Pharisee was zealous for the Torah. He may have been a member of the Sanhedrin, Judaism’s supreme court in the first century.

But he did all this as a layman. He could never lay claim to priesthood as he was born into the tribe of Benjamin, and Israel’s priesthood was restricted to the tribe of Levi.

Yet St. Paul clearly understood his role in priestly terms. In his Letter to the Romans, he spoke of his calling as “the grace given me by God to be a minister of Christ Jesus to the Gentiles in the priestly service of the gospel of God, so that the offering of the Gentiles may be acceptable, sanctified by the Holy Spirit” (Romans 15:15–16).

By grace, St. Paul had become a “minister.” In Greek the word is “leitourgon,” from which we get the English word “liturgy.” In St. Paul’s culture, this referred to a ritual and priestly role, not simply a job title for a religious administrator.

Thus, his work is a “priestly service,” and he further specifies that it is sacrificial. He speaks of the “offering of the Gentiles,” and prays that it may be “sanctified.”

St. Paul was speaking of himself in terms that were off-limits because of his genes.

Nevertheless, he employed such terms on many occasions. He spoke of his apostolate as a “ministry of reconciliation” (2 Corinthians 5:18). Again, in the Old Covenant, that role had been fulfilled by the priests, who brought about the forgiveness of sins through the expiating sacrifices of the Temple (see Hebrews 8:3). Now, St. Paul can describe himself as a “steward of God’s mysteries” (1 Corinthians 4:1), employing a common Greek term for religious rituals, “mysterion.”

St. Paul also identified himself as an “ambassador of Christ” (2 Corinthians 5:20; Philemon 9). The ancient rabbis said that an ambassador was to be received as the dignitary whom he represented. And indeed that is how the churches received St. Paul — they “received me,” he said, “as an angel of God, as Christ Jesus” (Galatians 4:14).

With the coming of Jesus, there had been a “change in the priesthood” (Hebrews 7:12). Jesus was the high priest of the New Covenant. In fact, St. Paul spoke of Jesus as both sacrificial priest and sacrificial victim (Ephesians 5:2).

But Jesus also shared his priesthood with men he designated as apostles; and he commanded them to offer the sacrifice of the New Covenant (1 Corinthians 11:25).

When St. Paul forgave sins, he said that he did so “en prosopo Christou” (“in the person of Christ”) (2 Corinthians 2:10). That Greek word “prosopo” is rich. It means “face.” It can also mean “person” or “presence.” St. Jerome translated the phrase into Latin as “in persona Christi.” Thus tradition has always read it: in the person of Christ.

That is how St. Paul understood his priesthood. His is the face God showed to the Gentiles. Like Christ, St. Paul saw himself as priest and sacrificial victim, “poured as a libation upon the sacrificial offering of your faith” (Philippians 2:17).

The priesthood is a call to self-giving. By the rite of ordination, the apostle conferred the gift of priesthood on a new generation (2 Timothy 1:6).

And so it has passed through the millennia, to the priests who serve our parishes today.