For those of us who can’t afford to buy all of the books we read, the library is as essential as a grocery store. We need books to remind us how deeply we are connected. We need books because we know we are going to die. Bewildered, alone, or despairing, we still have Anne Frank, Ivan Ilyich, Gregor Samsa.

Susan Orlean, a New York writer and author of the best-selling book “The Orchid Thief,” had frequented her local library as a kid. As an adult, living in New York City, she got into the habit of buying her own books.

In 2011, however, her husband accepted a job in LA. They moved to the Valley and one of her 6-year-old son’s first assignments was to interview someone who worked for the city. Orlean suggested a public library, so the two of them went to the Bertram Woods branch.

Entering a library again after all those years flooded Orlean with sensory memories. Everything was the same, she realized: the “creak and groan of the book carts,” the soft sound of pencils on paper, the “muffled murmuring” of the patrons, the raggedy community bulletin board.

“It wasn’t that time stopped in the library. It was as if it were captured here, collected here, and in all libraries — and not only my time, my life, but all human time as well. In the library, time is dammed up — not just stopped but saved. The library is a gathering pool of narratives and of the people who come to find them. It is where we can glimpse immortality; in the library, we can live forever.”

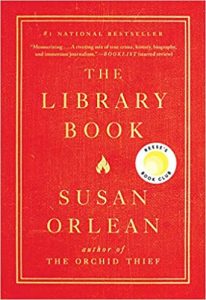

A door opened. “The Library Book” (Simon & Schuster, $13.69) is the fruit of what happened when Orlean stepped through it.

The book is ostensibly about the fire that ravaged the Central Library on April 29, 1986. A million books were damaged or destroyed. Irreplaceable artifacts were reduced to ash. The arsonist — if there was an arsonist — has never been found, though for years a would-be actor and fabulist Harry Peak was the suspect.

But Orlean’s triumph is really to champion the institution of the library in general, and in specific, our own Los Angeles Public Library.

Her book is meticulously researched, amplified by countless interviews, and made human by the innumerable visits she made to the library itself.

We learn of our city librarians, from John Littlefield in 1873, to Mary Foy in 1880, to Charles Lummis’ tumultuous reign from 1905 to 1910, to today’s John F. Szabo.

Every page is packed with compelling stories and factoids. The notes left in returned books, like messages in a bottle. One, from 1914, reads: “I have searched three cities for you and advertised in vain. Knowing that you like books, I am writing this appeal in every library book I can get hold of in hope that it may come to your eyes. Write to me at the old address, please.”

A wildly popular phone-in reference service was instituted in the 1930s, to which library patrons placed calls ranging from “What Romeo looked like” to “Number of Jewish families in Glendale” to “Whether immortality can be perceived in the iris of the eye.”

The science-fiction writer Ray Bradbury (1920-2012) spent almost every day for 13 years at the Central Library, reading through the stacks and educating himself as an alternative to college. “The library was my nesting place, my birthing place; it was my growing place.”

Bertram Goodhue’s Modernist-Art Deco temple, the Central Library at 630 W. 5th Street in downtown LA, had opened in 1926.

Critic Merrill Gage wrote in Artland News, “Like all creative art, it is disturbing: it leaves an impression that is satisfying yet mystifying. It follows no accepted method of architecture but through it strains of the Spanish, of the East, of the modern European, come and go like folk songs in a great symphony rising to new and undreamt-of heights in an order truly American in spirit.”

Almost 100 years later, that’s a kind of description of the city itself that still holds.

In fact, some of the most poignant passages are those describing the emotional devastation experienced by the library staff after the 1986 fire. People couldn’t sleep, eat. They worried that the patrons would feel abandoned. One woman wore white for several months, “hoping that would help her feel pure again.”

Volunteers appeared out of the woodwork; donations poured in. Approximately 700,000 books had been damaged. Restoring the Central Library collection would prove to be the biggest book-drying project ever undertaken. What could be salvaged was salvaged. Loss, eventually, was accepted.

After seven years, the last four in a cramped Spring Street location, the Central Library reopened. Today it serves more than 4 million people, the largest population of any public library in the U.S.

“A library is a good place to soften solitude;” observes Orlean, “a place where you feel part of a conversation that has gone on for hundreds and hundreds of years even when you’re all alone.”

Librarian Russell Garrigan had worked for the library department Teen’Scape for 17 years when Orlean asked if he enjoyed his job.

Garrigan replied, “Well, my hero is Albert Scwheitzer. He said, ‘All true living takes place face-to-face.’ ”