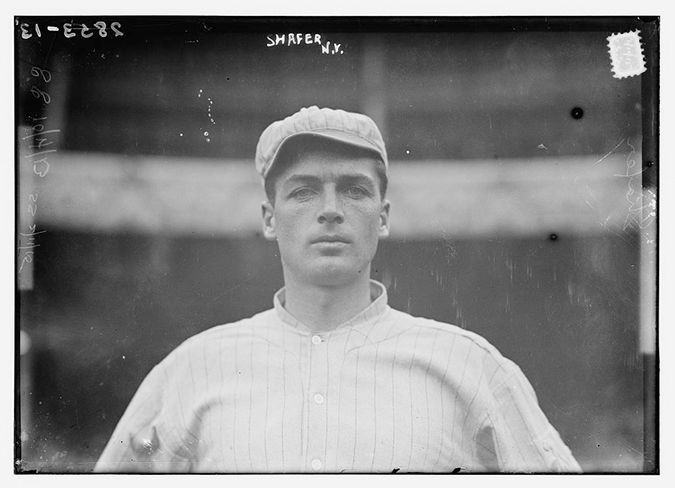

Tillie Shafer — that name ring a bell? Local product. Navy veteran of World War I. Amateur golf champ. Successful businessman. “Haberdasher to the stars” of the 1930s and ’40s. Good family man.

And, by all accounts, the very first product of a Los Angeles area Catholic high school to play in baseball’s World Series. Twice in fact, in 1912 and 1913, for the New York Giants.

Most famously, perhaps, this graduate of the high school division of St. Vincent's College — now known as Loyola Marymount University — had an all-too-close and personal view of one of baseball’s legendary mess-ups: the tenth-inning dropped fly ball by his friend and ex-St. Vincent’s teammate, Giants’ center fielder Fred Snodgrass, in the final game of the 1912 Series that led to the Boston Red Sox' 3-2 victory.

And it was Shafer who, incensed by his teammates’ post-game locker-room taunting of Snodgrass (“You cost us $1,500 apiece!”), came to his friend’s defense and — having already been soured on the professional baseball life, and the teasing he’d already endured from his teammates — retired soon after.

In an article for the Society for American Baseball Research, writer Brian McKenna noted that Tillie Shafer, who died at age 72 in 1962, was among the more iconoclastic players of his era — a college-educated son of well-to-do California parents who did not need to work for a living, but whose passion for sports drew him to a game (and a world) filled with, to a large degree, much-less-educated, much-less-well-off men whose comportment contrasted sharply with what Shafer had experienced.

From Lake Park to New York

Arthur Joseph Shafer was born March 22, 1889, and grew up in Los Angeles’ upper-class Lake Park District, the oldest of four children of successful businessman Frank and Alice Shafer. In 1904, Arthur (then 15) played second base for the St. Vincent’s College squad and soon played alongside future major leaguer Snodgrass (a Ventura High graduate), then a catcher.

At the University of Notre Dame Shafer — blessed with excellent speed — was a sprinter and long jumper on the track team, but — unhappy at Notre Dame — transferred to Santa Clara College, a baseball powerhouse, and spent three years there.

In 1908 he signed with the Giants (at Snodgrass’ urging, and to his father’s dismay) and spent four seasons (1909-13) playing infield and some outfield, compiling a .273 career average. His best season was his last, 1913, batting .287 with 32 stolen bases in 138 games, primarily at third base.

(He missed the 1911 season, in part because he went to Japan to train ballplayers there at Keio University — becoming the first active major leaguer to do so — and in part because he was miffed that the Giants had traded him to the Boston Braves, a deal later nullified.)

But his speed and aggressive play (which his feisty manager John McGraw liked) couldn’t make many fans among his teammates. Wrote McKenna: “Shafer was hassled from the moment he first entered the Giants' clubhouse. He was a young, good-looking, shy guy from a wealthy family unaccustomed to hardened East Coast athletes. He didn't drink, smoke or chase women — the typical ballplayer activities of the time.”

The Giants teased him as a “mama’s boy” and gave Shafer the nickname “Tillie.” Combined with the ridicule heaped on his buddy Snodgrass after the 1912 World Series, the death of his mother and his father’s desire for him to come back home, Shafer quit baseball. McGraw begged him to return for 1913, which he did, but only for that season. (He started all five games of the 1913 Series, which the Giants lost to Philadelphia.)

Shafer then devoted himself to his family’s businesses, became a top-flight amateur golfer, served during World War I at the Navy’s training station in San Diego, and in 1917 married Gwendolyn W. Shafer, with whom he had four children. He operated successful real estate and automotive agencies, a large fruit distributorship, and a men’s wear store that catered to celebrities.

And baseball? Shafer’s connection to the game essentially ended after he left the Giants, though he was contacted periodically about returning. "I have satisfied every ambition in a baseball way,” he said after retiring. “Now I want to forget I was ever in it…. I have plenty of money and I'm not dependent upon the $7,500 a year from the Giants."

But in 1933, he told Baseball Magazine that he regretted walking away from baseball. "I shouldn't have broken and run that way," he said. "I've been sorry ever since."

On Jan. 10, 1962, after a long illness, Tillie Shafer died at his home in Los Angeles. He is buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City.

Brian McKenna’s biography on Tillie Shafer was originally published as part of the Society for American Baseball Research Baseball Biography Project. To view the full article, see http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/7836aa82.