Much of the Catholic world this week has been focused on Hong Kong, where 90-year-old Cardinal Joseph Zen and five other defendants were found guilty of failing to register a pro-democracy fund, which is considered a crime under a new national security law imposed by Chinese authorities.

Zen has been ordered to pay a fine of $500.

Even if veteran commentator Nina Shea is right that the real penalty imposed by the trial isn’t so much the fine but the intimidation factor, effectively muzzling “China’s last globally prominent dissident,” the fact remains that Zen isn’t going to rot in jail. Should he elect to do so, he’s free to relocate someplace and continue his outspoken criticism of the Chinese regime.

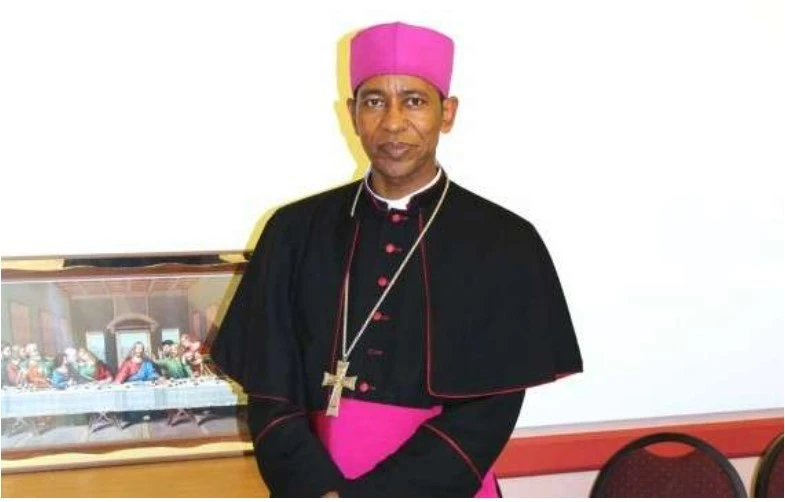

If you really want a Catholic bishop to worry about right now, a more harrowing choice probably would be Fikremariam Hagos Tsalim, the 52-year-old prelate of Segheneity in Eritrea, which is traditionally considered the cradle of Christianity in the country. Appointed in 2012, Tsalim was arrested by the regime on Oct. 15 and is reportedly being held in the notorious Adi Abeito prison on the outskirts of the capital city of Asmara.

At around the same time, two other Catholic priests were also arrested and both men, according to relatives, are also being held at Adi Abeito along with Tsalim.

As is par for the course in Eritrea, the three clerics have been detained without any legal proceedings or judicial review, they have no right to attorneys or to visitations, there’s no process to appeal their arrests, and the government has not commented on their case.

With regard to Tsalim’s long-term prospects, there’s abundant reason for concern.

Earlier this year, 94-year-old Abune Antonios, an Orthodox cleric in Eritrea, died in prison, having been kept in solitary confinement for the previous 16 years. Like Tsalim, Antonios was considered an enemy of the state for his criticism of the regime of Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki, who’s been in power since Eritrea gained independence from Ethiopia in 1991.

By virtually every measure available, Eritrea is considered one of the world’s worst offenders in terms of violations of religious freedom.

While precise counts are elusive, most estimates hold that somewhere between 2,000 and 3,000 Christians are currently languishing in Eritrean prisons for reasons related to their religious beliefs.

Many of those prisoners are kept in crude camps in the Eritrean desert, where inmates are packed into discarded 40-by-38 foot shipping containers, which generally are so crowded there’s no room to lie down and barely enough to sit. The metal exacerbates desert temperatures, meaning bone-chilling cold at night and suffocating heat during the day estimated to reach 115 degrees Fahrenheit or more. One former inmate, released after signing a coerced confession, described the containers as “giant ovens baking people alive.”

Here’s how another former prisoner, Evangelical gospel singer Helen Berhane, describes the reality at night.

“A single candle flickers, its flame barely illuminating the darkness. They never burn for more than two hours after the door is locked; there’s not enough oxygen to keep the flame alive. The air is thick with a dirty metallic tang, the ever-present stench of the bucket in the corner, and the smell of close-pressed, unwashed bodies. Despite the proximity of so many people, it’s freezing cold.”

Although Catholics are a small minority in Eritrea, estimated at no more than four percent of the population of six million people, they’ve long been a target of security forces because of the church’s criticism of the Afwerki regime.

In 2019, the government initially closed all Catholic hospitals in Eritrea, demanding that ownership be transferred to the state, and later also shuttered Catholic schools. The repression came after the country’s Catholic bishops, including Tsalim, issued a pastoral letter calling for greater human rights and religious freedom.

Tsalim has also criticized Eritrea’s role in a conflict in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia, where relations between Afwerki and his former allies in the push for independence from Ethiopia have soured.

“The regime constantly oppresses the Catholic Church in Eritrea, for ideological and political reasons mixed with profiteering, all designed to weaken its role as a voice of conscience,” said Father Mussie Zerai, an Eritrean who lives in exile in Switzerland and who’s known for his efforts to aid migrants crossing the Mediterranean Sea from North Africa to Europe.

“Catholic bishops in Eritrea have raised their voice to protest the illegal confiscation of church property and efforts to prevent the church from carrying out its mission in service to the people,” Zerai said. “Bishop Hagos is one of the few people [in the country] who defends the truth … he lives for his religious vocation.”

Here’s the reality of the situation.

Although the Afwerki government in Eritrea hardly feels beholden to Western standards of democracy and due process of law, it has shown itself sensitive to concentrated outside pressure. When Berhane was arrested in 2004, shortly after she’d released her first album of Christian music, the Evangelical world mobilized on her behalf and forged an international campaign for her release that included both Christian Solidarity Worldwide and Amnesty International.

By late October 2006, Berhane had become seriously ill because of the brutal conditions in which she was being held. Apparently fearing negative publicity should she die while in detention, the regime released Berhane, who was eventually granted asylum in Denmark along with her daughter Eva.

The question now is, will the Catholic community rise to Tsalim’s defense as the Evangelicals did for Berhane? Time will tell … and, given Eritrea’s track record, time may not be on Tsalim’s side.