No one can deny that politics, in America and around the Western world, is less stable and less predictable than it has been in at least a generation.

Whether one favors or deplores the rise of Donald Trump, the drama of Brexit, the daily protests in France, or right-wing triumphs in Europe and South America, everyone can agree that our assumptions about what is normal are being upended, and that the apparent security of post-Cold War globalism is looking less authentic by the day.

In this country, following similar movements elsewhere, one of the strongest challenges to the status quo is being mounted by a resurgent “new nationalism” or, as a recent conference in Washington, D.C. called it, “national conservatism.”

While the movement is not explicitly religious, it has been endorsed by prominent Christians, especially those affiliated with the conservative First Things magazine. It has also been rebuked by Christians, perhaps most notably in an open letter published by the more liberal Commonweal.

In a pair of open letters, the two magazines have squared off.

First Things opened with “Against the Dead Consensus,” arguing for an end to the awkward fusion of traditionalism and libertarianism that has defined American conservatism for decades in favor of a new focus on national solidarity: “We embrace the new nationalism insofar as it stands against the utopian ideal of a borderless world that, in practice, leads to universal tyranny.”

Meanwhile, Commonweal’s “Against the New Nationalism” responded passionately: “National identity has no bearing on the debts of love we owe other sons and daughters of God.”

In a sense, these documents argued past one another. The signers of the Commonweal letter see nationalism as intrinsically xenophobic, while the First Things signatories would attempt to articulate a nationalism that escapes their opponents’ bitterest critiques.

All this matters because these publications have in an important way defined the nationalism debate for Catholics, and understanding that debate will be essential to understanding their role in American politics in the coming years.

To begin, we have to look back at the complicated relationship between nationalism and liberalism.

When we talk about liberalism, we aren’t talking about the prevailing ideology of the Democratic Party, but rather the philosophy of individual rights and representative government that emerged from the Enlightenment and inspired revolutions across the Western world, including our own.

Different forms of nationalism have interacted with liberalism in different ways through time, but as a rule we can say that nationalism rises in response to an apparent crisis in the international order, triggering leaders and peoples to assert the priority of their own interests.

And so while nationalism and liberalism now seem to be at odds, they first emerged together, thanks in large part to the enemy they shared: The international order defined by absolute monarchy and the Catholic Church.

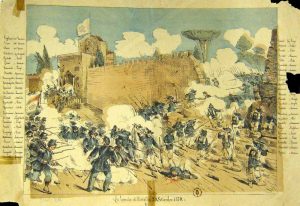

Perhaps the clearest example was the unification of Italy, which was an explicitly liberal, nationalist, and anti-papal crusade that culminated in the annexation of the Papal States to the new Italian nation-state.

But liberal-nationalist movements thrived across the continent during the long 19th century, each with the aim of bringing a cohesive ethnic coalition together under a single government to be able to assert its interests against the “tyranny” of the old order, and against other national powers.

World War I confirmed the new order of competing-and-sometimes-cooperating nation-states; “national self-determination” was on the lips of every liberal-minded designer of the international system.

Since then, aggressive nationalist movements have emerged when a nation or ethnic group feels ill-served by the rules of the system: Nazi Germany is, of course, the most potent example, but the nationalist-ethnic strife that followed the unwinding of the Soviet Union is a more recent one.

Now, nationalism is once again taking center stage in Europe and increasingly in America. Whereas centuries ago nationalist movements helped to usher in the liberal age, now they are seemingly trying to accelerate its demise. What broke up this relationship?

It’s a refrain you can hear in counseling sessions across the country: “My spouse changed. I just don’t recognize him anymore.” And that’s just what happened here: Liberalism morphed from a system for organizing the affairs of nations to a system for organizing the entire world.

Whether or not this is where liberalism was always going to end up, the bare fact is that the liberal-nationalist order of the 19th and early 20th centuries is now a liberal-internationalist order.

One implication of this development is that liberal ideology now aspires to achieve something only the Church has aspired to before it: the universal brotherhood of mankind. In fact, in this ambition we can see liberalism’s Christian roots, recognizing both the dignity of the individual and the natural aspiration to harmony with our fellow men.

Catholic critics of the new nationalism, such as the Commonweal writers, see in this attempt an authentic, if often quite flawed, reflection of the Church’s call for worldwide peace and justice. And whatever imperfections they identify, they see nationalism as a far more imperfect, indeed dangerous, alternative.

The new nationalists, on the other hand, see in the liberal order not a reflection but a parody of the Christian scheme. They see not genuine freedom but a liberal “imperium,” as one of the First Things writers, the Catholic convert Sohrab Ahmari, put it, an all-consuming international order that coerces nations and communities and families into affirming and embracing a strict ideology of individual autonomy.

Free trade, free speech (mostly), free sex (definitely): These are considered not just essential to the flourishing of a country, but to full participation in the international community. These nationalists see a world order that’s plunging deeper into moral, spiritual, and political crisis.

To their opponents, this is an unnecessarily dire description of the state of affairs. It looks and feels like a step backward to pull back from a globalism that, for all its flaws, seems to have brought a fuller appreciation for our shared humanity than even the Church, too often bound to parochial interests, has been able to achieve. The nationalists’ diagnosis might even look like a step toward fascist regimes that justified claims to total authority based on fear of “foreign” bogeymen.

The most conscientious proponents of this new nationalism are careful to dissociate themselves from those who argue for a strictly racial or ethnic basis for national identity, especially in the incredibly multiracial, multiethnic United States. And yet national identity must be based in something more than just voting in the same federal elections.

We could point to shared economic interests, shared cultural memory, and a shared language, but still: In a country of more than 300 million souls, finding truly substantive common ground is hard.

The fact is that the new nationalists are exactly correct that liberal individualism has stripped us of the identities and associations that give human beings earthly meaning and purpose. And they are also correct, against their critics who see liberal humanitarianism as a reasonably acceptable substitute for harmony in Christ, that one’s identity as a cog in the liberal global order is not enough to fill that void.

This is why identity politics, of the left and the right, has become such a force in our culture: We’re looking for something real to grasp about who we are.

But it is precisely the success of liberalism as a social solvent that makes a healthy nationalism so hard to envision. National identity is certainly one way to rediscover a middle ground between the individual and the globe — a middle ground that is natural, at least in the sense that it is essential to our psychology.

But without Christ, it quickly becomes an idol, and all idols are sources of inhuman rancor and division.

And so the Christian finds himself where he has always been: at the intersection of heaven and earth in his allegiances and identities, fully at home neither in the liberal “imperium” nor in a revived nationalism.

But that doesn’t mean the only answer is to despair of this world and to retreat into a sphere of private devotion; that would mean surrendering to precisely the liberal individualism that is in crisis.

So what’s a Catholic to do? How about starting with the hard work of rediscovering our primary identity in Christ, not just as a spiritual reality, but as an earthly, bodily reality. That means forming families and friendships and neighborhoods and parishes committed to their own common good, and then the common good of the societies they inhabit.

The Church is a people, and we share something more important than politics or economics or heritage or blood: We share in Christ on the cross and on the altar.

Only when we are assured in that identity, in that purpose, in that meaning can we transform an increasingly meaningless world.