The apostolic exhortation “Dilexi Te” (“I Have Loved You”) is the first official document from Pope Leo XIV. Signed on the feast of St. Francis of Assisi, it was actually begun by Pope Francis.

By choosing to finish a text that his predecessor had begun writing, Leo has signaled continuity with Francis, affirming a vision of the Church’s mission with the poor rooted in Scripture, tempered by realism, and for Leo, informed by a lifetime of missionary experience.

The document opens and closes with the same words: “I have loved you.” The symmetry feels deliberate, a reminder that the Gospel itself begins and ends in love — love that descends into human poverty and returns to God through the love of neighbor. Between those two words unfolds a meditation on how Christians can believe in the God who became poor for our sake.

“Dilexi Te” is not a social manifesto, though it touches on social questions. It is a theological reflection — Christ-centered, missionary, rooted in tradition with large portions dedicated to what saints have said on the issue, and contemplative. It asks Catholics to see poverty not merely as a problem to be solved, but also as a place where God is revealed.

How the document came to be

For those who know Leo’s biography, this perspective is not surprising.

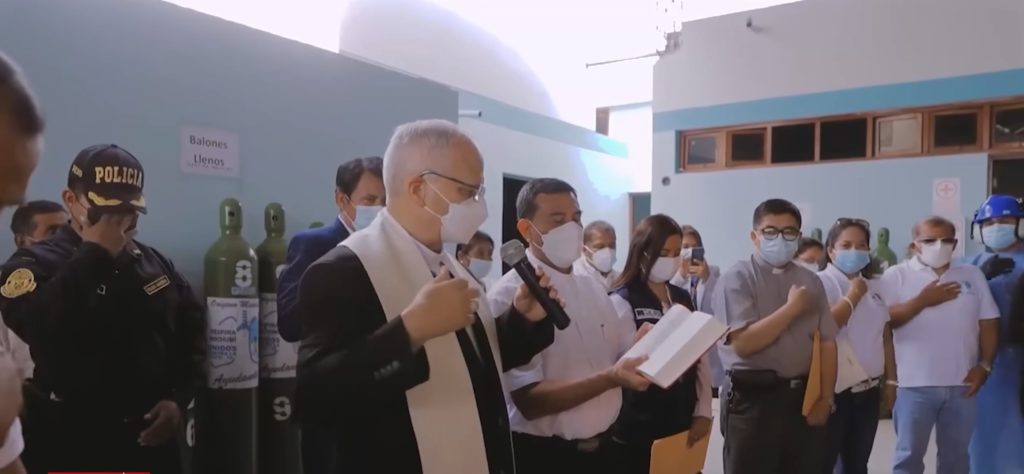

Long before his election to the papacy, Robert Prevost spent years living among the poor in Peru, accompanying small communities that measured wealth not in possessions but in faith, dignity, and resilience. That experience — of a Church both fragile and alive — permanently shaped his understanding of poverty.

We must “let ourselves be evangelized by the poor,” he writes, for they reveal the face of “the Son of Man [who] has nowhere to lay his head.” In these words, taken directly from the Gospels of Luke and Matthew, Leo captures what missionary life taught him: evangelization is not a one-way movement from abundance to need but a mutual exchange in which the poor become teachers of the Gospel’s essential truths — dependence, gratitude, and hope.

That said, the pope does not idealize poverty in “Dilexi Te.” He speaks of its brutality — of hunger, displacement, violence, and humiliation — in stark terms. To love the poor, he insists, is to work so that none may remain poor either due to injustice, indifference, or by design. Poverty may reveal Christ, but it is never acceptable as a permanent human condition.

Here lies one of “Dilexi Te’s” central insights: the tension between poverty as a problem and poverty as revelation. The Church must fight the causes of poverty even as she listens to what God teaches through those who suffer it.

What “Dilexi Te” says

The heart of the exhortation lies in its claim that poverty, rightly understood, unveils God’s presence in unexpected places. In the “cry of the poor,” Leo writes, we hear the echo of God’s first word to humanity: “I have observed the misery of my people.” To encounter the poor, then, is to be drawn back into salvation history, to the moment when God’s compassion became action.

“In hearing the cry of the poor,” he writes, “we are asked to enter into the heart of God, who is always concerned for the needs of his children, especially those in greatest need. “If we remain unresponsive to that cry, the poor might well cry out to the Lord against us, and we would incur guilt (cf. Deuteronomy 15:9) and turn away from the very heart of God.”

Leo’s document articulates a theology of poverty, not an ideology. He neither glorifies material want, nor reduces faith to activism.

“On the wounded faces of the poor, we see the suffering of the innocent and, therefore, the suffering of Christ himself,” he argues. In that revelation, the Christian discovers both the depth of divine mercy and the demand of discipleship.

For Leo, this is not abstract theology but incarnate reality. “The poor,” he writes, “are not a sociological category, but the very ‘flesh’ of Christ. It is not enough to profess the doctrine of God’s Incarnation in general terms. To enter truly into this great mystery, we need to understand clearly that the Lord took on a flesh that hungers and thirsts, and experiences infirmity and imprisonment.”

Why “Dilexi Te” matters

For Leo, love for the poor is a necessary part of holiness. That’s why, midway through the document, he invokes St. Gregory the Great, St. Francis of Assisi, St. Vincent de Paul, St. Pope John Paul II and St. Mother Teresa — who saw in the poor the clearest mirror of Christ. Love for the poor, he suggests, is not the invention of one pontificate or one theology. It is the perennial sign of authenticity for anyone who claims to follow Christ.

Yet Leo also broadens the meaning of poverty, describing it as a “multifaceted” phenomenon.

“The Lord says, ‘I have loved you,’ ” he writes throughout the document, to the hungry and to the refugee, to the woman stripped of her dignity and to the child robbed of innocence, to the drug addict to those who mourn, to those without medical care, to those who cannot speak freely, to those who are tired of being afraid. Poverty, in this sense, is not only economic but moral, emotional, spiritual, and relational — a web of suffering that cries out for redemption.

As someone who has witnessed poverty in both developing nations and urban centers of the United States, Leo knows that material aid alone cannot heal that which wounds the human spirit.

“The poor are not projects,” he warns elsewhere, “but persons through whom Christ continues to say: ‘I loved you.’”

If you want to know what Pope Leo XIV’s pontificate will hold for the future, “Dilexi Te” is key to understanding his pastoral vision: pragmatic, missionary, and convinced faith must be lived in proximity to human suffering.

The exhortation ends where it began — “I have loved you.” The repetition is more than literary; it is theological. We love because we have been loved first. In those three words, Leo sketches the horizon of his pontificate: a Church that does not idealize poverty but finds in it the face of Christ, and a love that becomes action — not sentiment, but service.