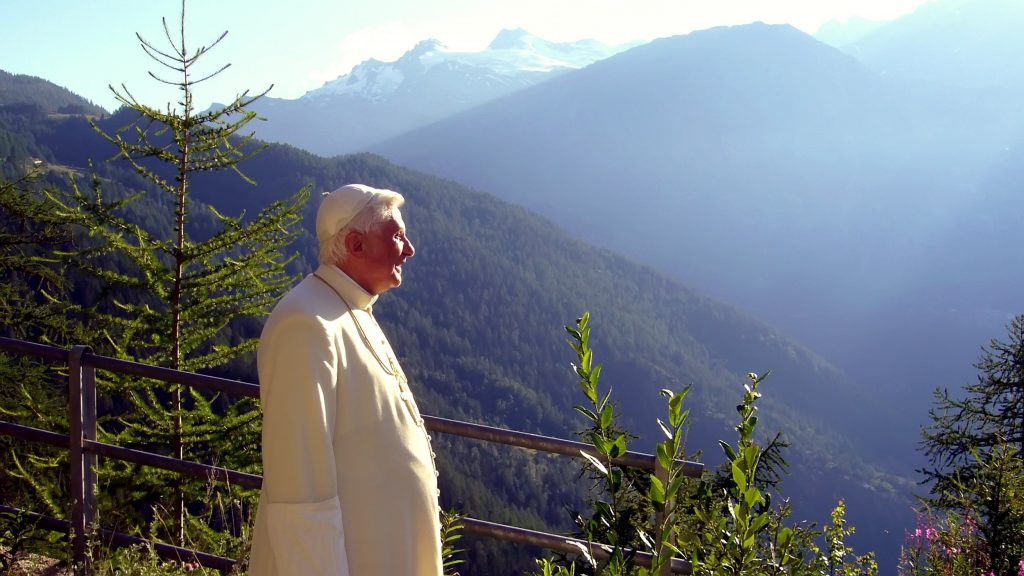

Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, a German theologian considered one of the greatest Catholic thinkers of his time, has died at the age of 95.

Cardinal Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger was elected pope on April 19, 2005, and took the name Benedict XVI. Eight years later, on Feb. 11, 2013, the 85-year-old shocked the world when he announced that he was resigning from the papacy, the first such action by a pope in nearly 600 years. He cited his advanced age and lack of strength as unsuitable for the exercise of his office.

Even before his election as pope, Ratzinger exerted a lasting influence on the modern Church, first as a young theologian at the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) and later as prefect of the Vatican’s Congregation (now Dicastery) for the Doctrine of the Faith.

An articulate defender of Catholic teaching, he coined the term “dictatorship of relativism” to describe secularism’s increasing intolerance of religious belief in the 21st century. Benedict’s pontificate was shaped by his deep understanding of this challenge to the Church in the face of rising ideological aggression.

He was also a key architect of the fight against sexual abuse in the Church in the early 2000s. He oversaw extensive changes to canon law and dismissed hundreds of offenders from the clerical state. He also launched a canonical investigation of the Legionaries of Christ, following growing allegations about grave sexual abuses from the order's founder, the Mexican priest Marcial Maciel Degollado.

Millions have read Benedict’s books, including the groundbreaking 1968 “Introduction to Christianity” and the three-volume “Jesus of Nazareth,” published from 2007 to 2012, during his time as pope.

After resigning in 2013, took up life in retirement in the Mater Ecclesiae monastery in the Gardens of the Vatican City State.

“I’m simply a pilgrim who is starting the last stage of his pilgrimage on Earth,” he said in his final words as pontiff. “Let’s go ahead together with the Lord for the good of the Church and of the world.”

He was known for his love of music — he played Mozart and Beethoven on the piano — as well as cats, Christmas cookies, and occasional draughts of German beer. The late pope was also renowned for his gentleness, courtesy, and for being a true child of Bavaria.

A higher call at a time of war

Joseph Ratzinger was born on April 16, 1927, Holy Saturday, in the Bavarian town of Marktl am Inn. His parents, Joseph and Maria, raised him in the Catholic faith. His father — a member of a traditional Bavarian family of farmers — served as a police officer. Joseph senior was, however, such a fierce opponent of the Nazis that the family had to relocate to Traunstein, a small town on the Austrian border.

Joseph and his older siblings, Georg and Maria, thus grew up during the rise of the Nazis in Germany, which he would later call “a sinister regime.” He was conscripted into the military’s auxiliary anti-aircraft service in the final months of World War II, deserted, and spent a brief time in an American prisoner-of-war camp.

After the war, he resumed studies for the priesthood and was ordained a priest on June 29, 1951, together with his brother, Msgr. Georg Ratzinger. The two remained close throughout their lives. A week before Georg died in 2020, Benedict traveled to Bavaria to say a final farewell to his older brother.

While Georg became a noted choirmaster, Joseph undertook doctoral studies in theology and ultimately became a university teacher and a dean and vice-rector at the prestigious University of Regensburg in Bavaria.

He served as an expert (peritus) at the Second Vatican Council for Cardinal Joseph Frings, the archbishop of Cologne. In 1972, he joined prominent theologians such as Hans Urs von Balthasar and Henri de Lubac in founding the theological journal “Communio” to reflect faithfully on theology in the tumultuous period after the council and to refute the various false interpretations of the conciliar documents that were being advanced.

Pope Paul VI appointed him archbishop of Munich and Freising in early 1977 and named him a cardinal in June of that year.

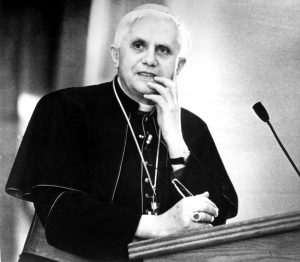

In 1981, Pope John Paul II named Ratzinger prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, president of the Pontifical Biblical Commission, and president of the International Theological Commission.

He played a decisive role in preparing the Catechism of the Catholic Church (published in 1992) and clarifying and defending Catholic doctrine. He was vilified for his labors by the secular media and progressive Catholic groups, especially when he fulfilled the task of investigating works by some theologians who proposed erroneous and even heretical teachings.

In 1997, at the age of 70, the then-cardinal asked John Paul II to allow him to resign his curial position so that he could work in the Vatican Library. John Paul II asked him to stay on, and he remained one of the key figures in the pontificate until the pontiff’s death in April 2005.

After the death of John Paul II, Ratzinger was elected to the papacy in one of the shortest conclaves in modern history.

A call for renewal

Cardinal Ratzinger chose the name Benedict XVI because, as he explained at a general audience only days after his election, Benedict XV (pope from 1914–1922) had also steered the Church through a period of turmoil, in the First World War (1914–1918).

Benedict’s papacy was marked by efforts at ecclesiastical, intellectual, and spiritual renewal, including confronting relativism and secularism, combatting the scourge of clergy sexual abuse, pushing for liturgical reform, and promoting further an authentic interpretation of the Second Vatican Council.

In his homily ahead of the 2005 conclave that elected him to the papacy, the soon-to-be pope warned of a “dictatorship of relativism that does not recognize anything as definitive and whose ultimate goal consists solely of one’s own ego and desires.”

In his speech in Westminster Hall to the leaders of British Society during his visit to the United Kingdom in 2010, he spoke about the immense dangers to contemporary society when religion is driven from the public square.

“There are those who would advocate that the voice of religion be silenced,” he said, “or at least relegated to the purely private sphere. There are those who argue that the public celebration of festivals such as Christmas should be discouraged, in the questionable belief that it might somehow offend those of other religions or none.

Far more controversial was his 2006 address at the University of Regensburg, where he criticized forms of secular thought that promote “a reason which is deaf to the divine and which relegates religion into the realm of subcultures,” deeming this attitude “incapable of entering into the dialogue of cultures.” He also criticized schools of Christian and Muslim thought that wrongly exalt God’s “transcendence and otherness” so that human reason and understanding of the good “are no longer an authentic mirror of God.”

Some media and several German politicians purposefully took that speech out of context, focusing on a single, ancient quotation from a Byzantine emperor. This misrepresentation was accompanied by an outburst of anti-Christian violence across parts of the Muslim world.

Despite such reactions, Benedict’s actual contribution led to more significant efforts at a sincere Christian-Muslim dialogue — one that does not paper over differences and that calls for mutual reciprocity in the respect of rights.

Having recognized the deep existential and spiritual crisis facing the world, the West in particular, Benedict reminded Catholics everywhere of the call to evangelize. He was a major supporter of the new evangelization, especially in preaching and living the Gospel across what he described as the “digital continent,” the world of online communications and social networking.

Competing views of Vatican II

Benedict saw the need also for the Church to embrace an authentic understanding of the Second Vatican Council, noting in a seminal speech given in 2005 two competing interpretive models (hermeneutics) that had emerged after the council.

The first, a hermeneutic of discontinuity and rupture, proposes that there is a fundamental break between the council and the past and that a certain “spirit of the council” should guide its interpretation and implementation. Benedict lamented: “In a word: It would be necessary not to follow the texts of the council but its spirit. In this way, obviously, a vast margin was left open for the question on how this spirit should subsequently be defined and room was consequently made for every whim.”

Against the hermeneutic of rupture, Benedict proposed a hermeneutic of reform and continuity that he called “renewal in the continuity of the one subject-Church which the Lord has given to us. She is a subject which increases in time and develops, yet always remaining the same, the one subject of the journeying People of God.”

The call to continuity and reform found rich expression in the pope’s attention to the liturgy, in particular through his book “Spirit of the Liturgy” (2000) and his efforts to encourage a return to reverence and beauty in liturgy.

“The real ‘action’ in the liturgy in which we are all supposed to participate is the action of God himself,” he wrote. “This is what is new and distinctive about the Christian liturgy: God himself acts and does what is essential.”

In 2007, he issued the apostolic letter Summorum Pontificum, which significantly broadened permission for priests to celebrate Mass according to the missal prior to the reforms of 1970. He wrote in Summorum Pontificum: “In the history of the liturgy there is growth and progress, but no rupture. What earlier generations held as sacred, remains sacred and great for us too, and it cannot be all of a sudden entirely forbidden or even considered harmful. It behooves all of us to preserve the riches which have developed in the Church’s faith and prayer, and to give them their proper place.”

His efforts at reforming the Roman Curia were left incomplete at the time of his resignation. Media attention focused especially on the so-called Vatileaks scandal, involving the leak of private papal documents and the arrest and trial of a papal butler. Nevertheless, he took important steps toward genuine financial transparency that were likewise carried forward by Pope Francis.

Taking a firm stand on abuse cases

Long before his election as pope, then Cardinal Ratzinger had pushed for serious efforts at confronting the scourge of clergy sexual abuse. In 2001 he was instrumental in having abuse cases placed under the jurisdiction of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and helped the U.S. bishops receive Vatican approval for the Dallas Charter and the Essential Norms that then formed the basis for the immense progress in dealing with clergy abuse in the United States.

In the days just before the death of Pope John Paul II, in March 2005, Ratzinger wrote meditations for the Way of the Cross on Good Friday in Rome. In his reflection on the ninth station, he made the searing condemnation, “How much filth there is in the Church, even among those who, in the priesthood, should belong entirely to him!” The comments forecast his commitment to the fight against abuse from the moment of his election.

Two months into his papacy, Benedict disciplined Father Marcial Maciel, the charismatic and influential founder of the Legionaries of Christ who had long been accused of sexually abusing seminarians and was later revealed to have led a deeply scandalous double life.

His pontificate was marked by formal apologies to victims of sexual abuse, including those in the United States, Australia, Canada, and Ireland. In 2008, during his visit to the United States, he met personally with victims, and in 2010, he wrote a pastoral letter to the Catholics of Ireland asking their forgiveness for the enormous suffering caused by abuse.

“You have suffered grievously,” he wrote, “and I am truly sorry. I know that nothing can undo the wrong you have endured. Your trust has been betrayed and your dignity has been violated. Many of you found that, when you were courageous enough to speak of what happened to you, no one would listen.”

A distinguished teacher and theologian

Despite his advanced years at the time of his election, Benedict continued John Paul II’s habit of traveling around the world. His 25 apostolic visits outside Italy included three trips to his native Germany and three World Youth Days.

Benedict canonized 45 new saints during his pontificate, including Damien de Veuster, the leper priest of Molokai (2008); the French Canadian André Bessette (2010); and Kateri Tekakwitha (2012), the first Native American saint. He had the unique distinction of allowing the start of the cause of canonization of his predecessor, John Paul II, and presided at his beatification in 2011. (St. John Paul II was canonized in 2014 by Pope Francis.)

He also named two doctors of the Church in 2012, the medieval German mystic and abbess St. Hildegard of Bingen and the Spanish priest St. John Ávila.

His three encyclicals, Caritas in Veritate, Spe Salvi, and Deus Caritas Est, stressed the theological virtues of love and hope. Pope Francis incorporated Benedict’s unfinished encyclical on faith into his own 2013 encyclical Lumen fidei.

Benedict’s fame as a theologian and author already was established internationally before his election to the papacy. His books included “Introduction to Christianity,” a compilation of his university lectures on the faith in the modern world. His interview books were major best-sellers, including “The Ratzinger Report” (1985) with Vittorio Messori, “Salt of the Earth” (1996), “God and the World” (2000), and “Light of the World” (2010) with the German journalist and author Peter Seewald. One of the popular works under his name was the trilogy “Jesus of Nazareth,” an effort to explain Jesus Christ to the modern world.

A pope emeritus

Benedict led a life of prayer and reflection after the election of Pope Francis, occasionally consulting and meeting with his successor. Ultimately, his time in retirement and seclusion was longer than his pontificate.

Occasional public interventions sparked intense reactions and debate. In 2019, he contributed to the discussion on the abuse crisis with an essay, going to the heart of the matter — the dictatorship of relativism that he had warned about in 2005.

“Today, the accusation against God is, above all, about characterizing His Church as entirely bad, and thus dissuading us from it. The idea of a better Church, created by ourselves, is in fact a proposal of the devil, with which he wants to lead us away from the living God, through a deceitful logic by which we are too easily duped," he wrote.

"The Church of God also exists today, and today it is the very instrument through which God saves us.”

In July 2021, the then 94-year-old retired pope warned of a Church and doctrine without faith, saying: “Only faith frees man from the constraints and narrowness of his time.”

In February 2022, Benedict issued a letter addressing a report on abuse in the Archdiocese of Munich-Freising that faulted him for his handling of abuse cases during his time as archbishop in the late 1970s. In it he once again expressed to all the victims of sexual abuse his profound shame, his deep sorrow, and his heartfelt request for forgiveness.

The letter served in many ways, too, as a final meditation on his life in retirement but also the abiding faith that characterized his labors on behalf of Christ and his Church.

“Quite soon,” he wrote, “I shall find myself before the final judge of my life. Even though, as I look back on my long life, I can have great reason for fear and trembling, I am nonetheless of good cheer, for I trust firmly that the Lord is not only the just judge, but also the friend and brother who himself has already suffered for my shortcomings, and is thus also my advocate, my ‘Paraclete.’

"In light of the hour of judgment, the grace of being a Christian becomes all the more clear to me," he continued. "It grants me knowledge, and indeed friendship, with the judge of my life, and thus allows me to pass confidently through the dark door of death.”

Pope Francis is expected to celebrate Benedict XVI’s funeral Mass.

Reporting courtesy of CNA Deutsch Editor-in-Chief AC Wimmer, former CNA Europe editor Luke Coppen, and EWTN’s Dr. Matthew E. Bunson.