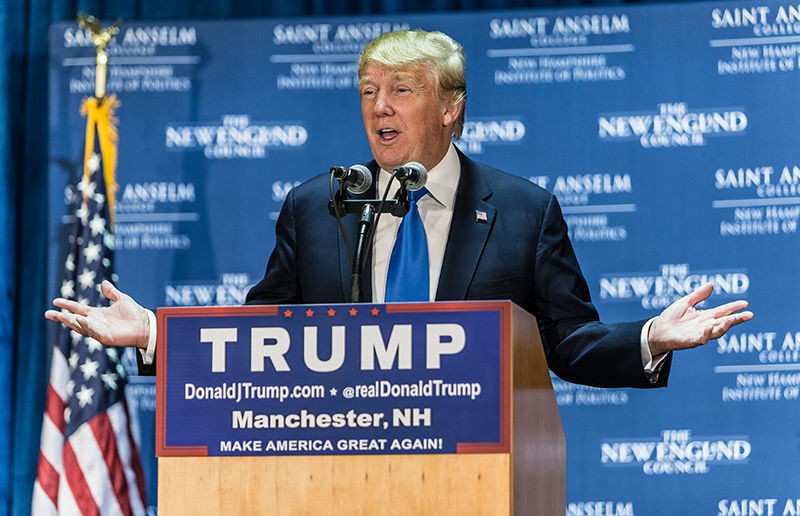

The potential presidential candidacy of Donald Trump, a media critic when it suits his purposes, is a creature of the media. Trump has a knack for saying outrageous things, and journalists have heaped lavish free coverage on his outrageousness.

The result: a candidate who has never held public office and has made the art of personal insult a significant part of his chosen path to the White House.

Piety probably isn’t going to solve this problem, but in the Jubilee Year of Mercy proclaimed by Pope Francis a concerted prayer campaign for an end to the politics of outrage and insult could only help. This is not just a matter of practicing civility and niceness.

Nothing less than the common good of the nation is ultimately at stake here, and it is no violation of church-state separation to pray earnestly for that.

However all this turns out, the media response to the Trump phenomenon represents pack journalism at its worst. One reporter records the candidate’s latest outrageous remark, so all the reporters feel they must do it, too. And they have kept on doing it, over and over again, up to the eve of the primary season that’s now hard upon us.

Perhaps the journalists believe that they make amends for giving so much attention to Trump by joining their coverage with frequent name-calling. But in fact even the name-calling seems to help Trump.

Every knock a boost appears to be the name of the strange game being played by the candidate and the press.

Pack journalism has always been a journalistic fault, but it’s become more of one in the age of the Internet and Twitter. Covering the news under any circumstances is a rapid-fire enterprise in which deadlines play a crucial role and accuracy is forever at risk.

But now we are reaping the dubious advantages of a competition-driven 24/7 news cycle produced by the advent of new media technology. The results are not pretty to behold.

I was reflecting on these depressing matters when I came upon a post-Christmas goodbye column by Walter Pincus, a serious journalist who has written coverage and commentary on national security affairs for The Washington Post for more than 40 years.

Pincus took his leave by voicing three concerns about the news business. Although he didn’t mention Trump, what he said fits.

One concern was how much the influence of media has grown in these four-plus decades, thanks largely to the revolution in media technology. Next was the increased skill of newsmakers at using media to shape what the public gets told according to the way they want it told.

“In many ways,” Pincus wrote, “I feel that journalistic ventures have become ‘common carriers,’ printing whatever newsmakers say — even if they know it to be untrue or inflammatory — just because … such stories generate readers, viewers and, these days, hits on the Web.”

His third concern was this:

“The current competitive rush to be first in both breaking news and slick commentary is leaving behind the facts. … The public is left to make up its mind on important subjects by choosing between arguments without knowing much about the facts that may or may not underlie them.”

In short, Pincus concluded, we are increasingly becoming a society in which public relations is “a key part of government and our politics.”

Via the Trump campaign, the politics of outrage and electronic pack journalism are now delivering a powerful symbiotic one-two punch to the common good. Should we be worried about that? You bet we should.

Russell Shaw, a contributing editor to Our Sunday Visitor, writes from Washington, D.C.