We begin in 1206. Hubert Walter, archbishop of Canterbury, dies.

No.

We begin with King Henry II of England and Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine. They had seven children. They should have stopped at six. The nicest thing contemporary chroniclers say about their youngest son, John Lackland, is that he was “brimful of evil qualities.” “No man may trust him,” sang the troubadour Bertran de Born, “for his heart is soft and cowardly.”

In the Age of Chivalry, John’s barbarities are legion.

With Canterbury’s see open, King John tells the pope he wants a worthless toady to be the new archbishop. Pope Innocent III has his own candidate: Stephen Langton.

Langton is one of the most humble, most learned, most spiritual men of the age. Receiving a basic education at Lincolnshire’s cathedral school, Stephen travels to the new university at Paris. By age 30 he becomes a professor of biblical theology.

Now, Master Langton is no radical, but he uses scriptural precedent to teach that kings and nobles are subject to the law, same as everybody else. “If a king condemns a man to death but the prisoner has not been convicted by a court,” Langton might ask, “is the executioner obliged to carry out the sentence?” Students flock to his classes.

Impressed with his piety and learning, Pope Innocent calls Langton to Rome and ordains him a cardinal priest. In June 1207, Innocent consecrates Langton bishop and blithely informs King John that Cardinal Langton is England’s new primate.

John now demonstrates his talent for making difficult situations worse. He refuses to accept Langton — but Innocent III was the wrong pope to make demands of.

After a year of King John Lackland’s diatribes, Innocent excommunicates him. John threatens to kill Langton the day he returns. Innocent places England under interdict: Church doors are locked, the celebration of Mass forbidden. Administration of sacraments ceases, save for extreme unction in the face of death.

The barons want John to stop the nonsense — and stop bleeding them with arbitrary “fines.” They begin plotting against him.

Fed up, in 1212 Pope Innocent releases John’s subjects from their allegiance. When King Philip Augustus of France suggests that he invade England, Pope Innocent blesses the endeavor. Philip gleefully assembles an army.

Realizing that the game’s up, John finally does something uncharacteristically brilliant. He gives in and sends his crown to Innocent III. This makes England a papal fiefdom. John becomes the pope’s vassal: attacking him is attacking the pope.

Cardinal Langton returns to England in 1213. Lifting John’s excommunication, Langton reminds him of the Charter of Liberties proclaimed by his predecessor, Henry I, in 1100. John agrees but, almost immediately, breaks his word.

Despite John’s depredations, Langton abhors the prospect of death and destruction inflicted by civil war, pleading with the barons to not take up arms against their king, the Lord’s anointed. The barons give Langton a chance to get John to stop fining them by executive or … I mean, by royal decree.

In a spirit of peaceful settlement, Magna Carta was born.

It’s likely that Langton wrote the bulk of the charter enshrining so many of his own principles, the basis of governmental recognition of individual freedoms.

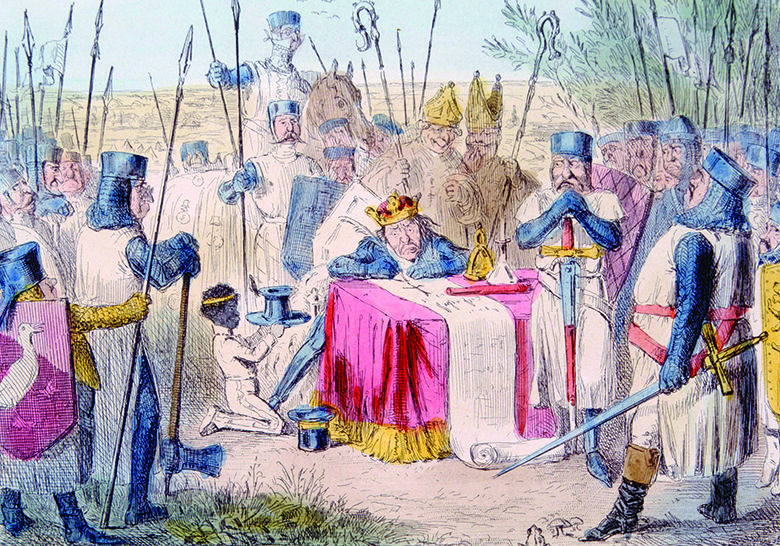

Langton invites the king and the barons to a meadow at Runnymede on June 15, 1215. John affixes his royal seal to the 3,500 words written on calfskin parchment.

In Great Britain this June 15, massive celebrations commemorated the 800th anniversary of this event. Queen Elizabeth II, Prime Minister David Cameron, the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, attended, as did U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch.

If you blinked during news programs, you missed U.S. coverage.

Despite the efforts of Cardinal Stephen Langton, the only mentions of Catholic involvement in newspapers were snickers about Pope Innocent III.

Duplicitous as ever, Lackland wrote Innocent, complaining that the terms were forced upon him. Without any other information, Innocent annulled Magna Carta three weeks after John “accepted” it.

In November of 1215, Cardinal Langton traveled to Rome, attending the Fourth Lateran Council which, among other lasting decrees, dogmatically accepted Transubstantiation to explain the miracle of the Holy Eucharist.

Pope Innocent snubbed Langton and deposed him from his position at Canterbury. Dying in 1216, Innocent was succeeded by Honorius III, whose first papal actions were to accept Magna Carta and reinstate Cardinal Langton.

Back in England, Cardinal Langton introduces the Elevation of the Sacred Host at Mass so that all might adore the eucharistic Jesus. He’s credited with composing the sublime sequence “Veni Sancte Spiritus,” heard at Masses on Pentecost. His division of the Bible into chapters is followed to this day.

Cardinal Stephen Langton, a noble example for any bishop to follow, continued to produce voluminous writings and led the Church in England in the struggle for freedom until his death in 1228.

And England has never had another king named John.