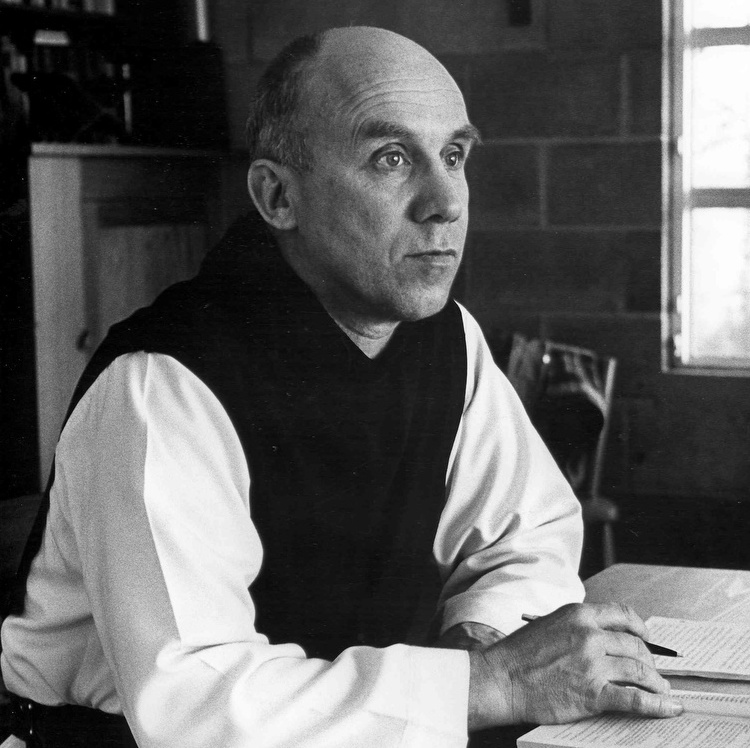

Thomas Merton was a man of many contradictions: a Trappist contemplative who advocated political protest, a poet who believed silence was the ultimate eloquence, a social critic who distrusted sociological categories, and a world-famous hermit.

These paradoxes don’t untie themselves easily, if at all, and so it is an occasion of some significance when one of our most accomplished contemporary Catholic writers — Mary Gordon — attempts to disentangle some of the confusion through a candid appraisal of his work.

Gordon may be the perfect person for this task. She is a novelist, essayist, and master of the short story.

Her works include “There Your Heart Lies” and “Final Payments,” six works of nonfiction, including “Reading Jesus” and the prize-winning collection “The Stories of Mary Gordon.” She is also a professor at Barnard, a New Yorker, a feminist, and a lifelong Roman Catholic.

Her book “On Thomas Merton” grew out of a lecture she delivered on the 100th anniversary of Merton’s birth when the Columbia Rare Book and Manuscript Library prepared an exhibition of his papers. As Gordon tells it, she was selected because she was “the only literary person on the Columbia campus known to be a practicing Catholic.”

Shambhala Publications then asked her to turn the lecture into a book, but she admits she kept asking herself, “Why me?”

“As I became aware of the mass of books and articles written about Merton the question became more pressing. And I could only answer it in one way: I am a writer. I wanted to write about him writer to writer.”

But what kind of writer was he?

“For Thomas Merton,” Gordon tells us, “writing was always about making sense of the world; and an important part of that enterprise was making sense of himself as a writer. It is a commonplace for people to say, ‘I don’t know what I think until I write it,’ but Merton took it a step further: he didn’t know who he was from moment to moment, until he wrote.

Merton said as much when he confessed, “It is possible to doubt whether I have become a monk (a doubt I have to live with) but it is not possible to doubt that I am a writer, that I was born one and will most probably die as one.”

Gordon finds the tension between Merton’s calling as a monk (with its vows of silence and obedience) and his equally strong calling as a writer (with its obligations to honesty, accuracy and complete candor) “a supersaturated, or perhaps super-distilled, form of the conflict that strikes every artist: the conflict between being an artist in solitude and being a human in the world.”

She begins with Merton’s most famous work, “The Seven Storey Mountain,” (1948) because it presents both the best and worst sides of Merton as a writer: “The pious, closed, almost inhuman voice is there, but so is his greatest gift: his power of close observation.”

After examining several passages, Gordon is happy to note that Merton ultimately disavowed the book’s “triumphalist rhetoric,” “Manichean self-loathing,” “hatred of the world and flesh” and “cavalier dismissal of other faith traditions.”

“Indeed,” she reminds us, “as early as 1951, Merton declared that the man who wrote that book was dead.”

“The next twenty remaining years of Merton’s life,” Gordon claims, “will be a series of convulsions that will topple the certainty of the Mountain that brought him to the attention of the world, perhaps blocking the world’s view of the living man, and forcing the writer into postures and forms that would limit his creative possibilities.”

Gordon then turns to one of the novels Merton wrote before he entered the monastery — “My Argument with the Gestapo” — as an example of the kind of writer Merton might have become had he not become a monk.

It is an inspired move, for not only was it written between the wars, at a time not unlike our own, when democratic societies throughout the world were under threat, but, as Gordon so eloquently observes, it contains “in a particularly concentrated form the subjects that would dominate [Merton’s] writing for the rest of his life: the problem of war and violence, his particular calling as a writer, and his vexed identity as an American whose imagination has been found in and marked by Europe. And woven in a pastel thread through the saturated primary colors of the cloth, is Merton the convert making his way through the world with a new anointing.”

Gordon speculates that had Merton continued to write in this bracing, Joycean fashion, he probably would have been marginalized (if not completely ignored) by the critics of his day. The contemporary “preponderance of Hemingwayesque prose with the emphasis upon the tough guy or the ironic stance” was completely antithetical to Merton’s purposes as a writer.

Merton’s “success,” Gordon later writes, “came about, then, not from following the daring path of “My Argument with the Gestapo,” but by turning radically away from it, becoming the writer-monk, writing what would be of use: to the Trappists, to the Catholic Church, for the salvation of what he would call ‘the hearts and minds if men,’ and what his superiors would call ‘soul.’ ”

This is harsh criticism which is compounded by the fact that it’s probably true.

“But then,” Gordon immediately adds, “there are the journals.”

Merton’s journals, from Gordon’s point of view, are his most lasting contribution to contemporary letters. His best ideas are born there, as are his most unvarnished descriptions of embodied spiritual experience.

Their open, multi-valent, dialogic form is perfectly suited to Merton’s unique gifts as a writer, and, although Gordon doesn’t use the term herself — the journals bring Catholicism into direct conversation with what can only be described as postmodernism.

“To be postmodern,” Gordon once wrote, “is to be, above all, aware of the partiality and incompleteness of our knowledge, and of the horrors that have come about from what we have not seen, could not see, failed to see.”

And her book on Merton makes it quite clear — that no matter how much we might wish otherwise, Merton shares this challenging awareness with the rest of us. And it was his integrity as an artist — even more than his monastic vows — that made that possible.

Consider Merton’s description of his work written in 1966.

“This is simply the voice of a self-questioning human person who, like all his brothers, struggles to cope with the turbulent, mysterious, demanding, exciting, fascinating, confused existence in which almost nothing is really predictable, in which most definitions, explanations, and justifications become incredible even before they are uttered, in which people suffer together and are sometimes utterly beautiful, at other times impossibly pathetic. In which there is much that is frightening, in which almost everything public is patently phony, and in which there is at the same time an immense ground of personal authenticity that is right there and so obvious that no one can talk about it and most cannot believe that it is there.”

I have always found Soren Kierkegaard’s distinction between the genius and the apostle helpful in sorting out Merton’s Joycean summersault over modernism into what he called “his own empty and disconcerting experience of faith.” “The genius,” Kierkegaard wrote, “has only and immanent teleology,” the apostle is “absolutely, paradoxically, teleologically placed.”

As a writer, Merton sought to fulfill a distinct set of human potentialities by creating exemplary works; whereas, Merton, the apostle, existed in a paradoxical relationship to the entire human enterprise — an absolute dissident and metaphysical rebel whose primary contribution was to expose the contradictions in himself and in his times by downing them in the light of a higher revelation.

Like any writer, Merton was only “sometimes” a genius, but as a contemplative monk, he was always an apostle — perpetually at odds with his time, pen bravely tilted against Kitsch Catholicism and the techno-corporate idols of our age.

What we have in Gordon’s reflection is one Catholic genius/apostle in conversation with another. And so it is fitting that she ends this concise, powerful, and thought-provoking set of observations with a line from Merton’s “Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander”: “The beauty of God is best praised by the men (and the women) who reach and realize their limit, knowing that their praise cannot attain to God.”

Robert Inchausti is the author of “Thomas Merton’s American Prophecy” (SUNY Press, 1998) and editor of “Echoing Silence: Thomas Merton on the Vocation of Writing” (Shambhala, 2007).

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!