With a revision of the Church’s Catechism, Pope Francis has declared capital punishment “inadmissible,” but the development will be a hard sell for some Catholics

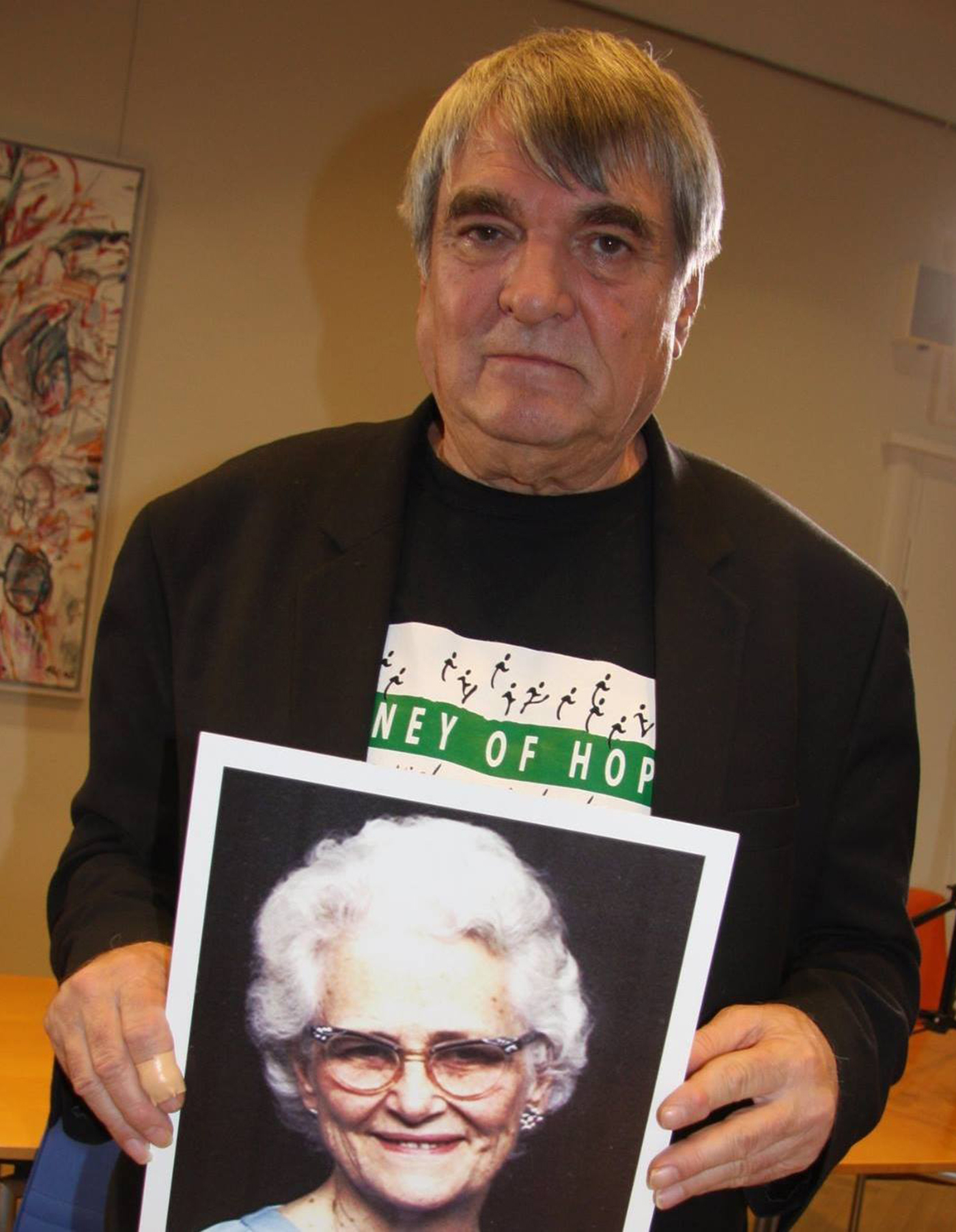

Life and death, hatred and forgiveness, are not strangers to Bill Pelke — three decades ago, a gang of teenage girls brutally murdered his 78-year old grandmother.

All for $10 to play arcade games.

“She was the perfect grandmother,” Pelke said.

Ruth Elizabeth Pelke was a deeply faithful Christian woman, who spent her Sundays immersed in worship and church activities. She frequently held Bible classes so others would come to know the saving love of Jesus.

She gave her life for that witness on July 11, 1986, when four teenagers knocked on her door, asking for information about her Bible studies. It was a ruse: the girls had plotted to rob Ruth.

One girl struck Ruth with a lamp, and the ringleader, Paula Cooper, stabbed her 33 times.

Even though she was a teenager with a deeply troubled family history, Cooper was sentenced to death by electric chair. At the time, Bill Pelke felt her sentence was justified. But three months after Cooper’s sentencing, Pelke underwent a total change of heart and joined his voice with St. Pope John Paul II in calling for mercy.

“I became convinced through my grandmother’s life that the answer was love and compassion for all humanity,” he said. “And you can’t do that when you put somebody in the death chamber. That’s impossible.”

Cooper’s sentence was commuted to 60 years in prison. Pelke, now a retired steelworker, decided to co-found Journey of Hope, an organization of murder-victim family members dedicated to educating and promoting death penalty alternatives.

“The pope’s message is the same one that I have shared for years and years now: the answer is love and compassion for all humanity,” he said. “The answer is forgiveness.”

Pelke told Angelus News that he had waited 30 years to read the news he received on his phone on August 2. The Vatican announced Pope Francis approved a change to the Catechism of the Catholic Church that declared the death penalty “inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person.”

For Pelke, Pope Francis had finally finished what St. Pope John Paul II started in his 1995 encyclical “Evangelium Vitae” (“The Gospel of Life”).

Abolition and debate

In the U.S., the pope’s announcement has galvanized death penalty abolitionists, but not ended the debate among Catholics about the justice of the death penalty.

According to a 2018 Pew Research Center survey, 53 percent of Catholics favor the death penalty, while 42 percent remain opposed.

Catholic political leaders remain divided. Gov. Andrew Cuomo of New York announced a new push to abolish the death penalty, but Gov. Pete Ricketts of Nebraska indicated the state would move forward with its first lethal injection based on an untested drug combination.

U.S. Catholic bishops and leaders welcomed the change as a call to arms to abolish the death penalty in 31 U.S. states, where 2,400 men and women live on death row.

In a letter to the world’s bishops, Cardinal Luis Ladaria, prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, outlined how the Catechism’s new language builds on the teaching set forth by Pope John Paul in “Evangelium Vitae.”

Cardinal Ladaria explained how the 1994 Catechism was revised in 1997 to reflect “Evangelium Vitae’s” teaching that the state could not invoke the death penalty as a “proportionate penalty for the gravity of the crime,” but could only justify it as “the only practicable way to defend the lives of human beings effectively against the aggressor.”

The 1997 Catechism stated such cases of social self-defense were “practically nonexistent,” but a number of Catholics, particularly in the U.S., maintained those conditions were a matter of prudential judgment.

Cardinal Ladaria’s letter explained to bishops why the death penalty in the modern era is incompatible with the Church’s teaching on the sacredness of human life.

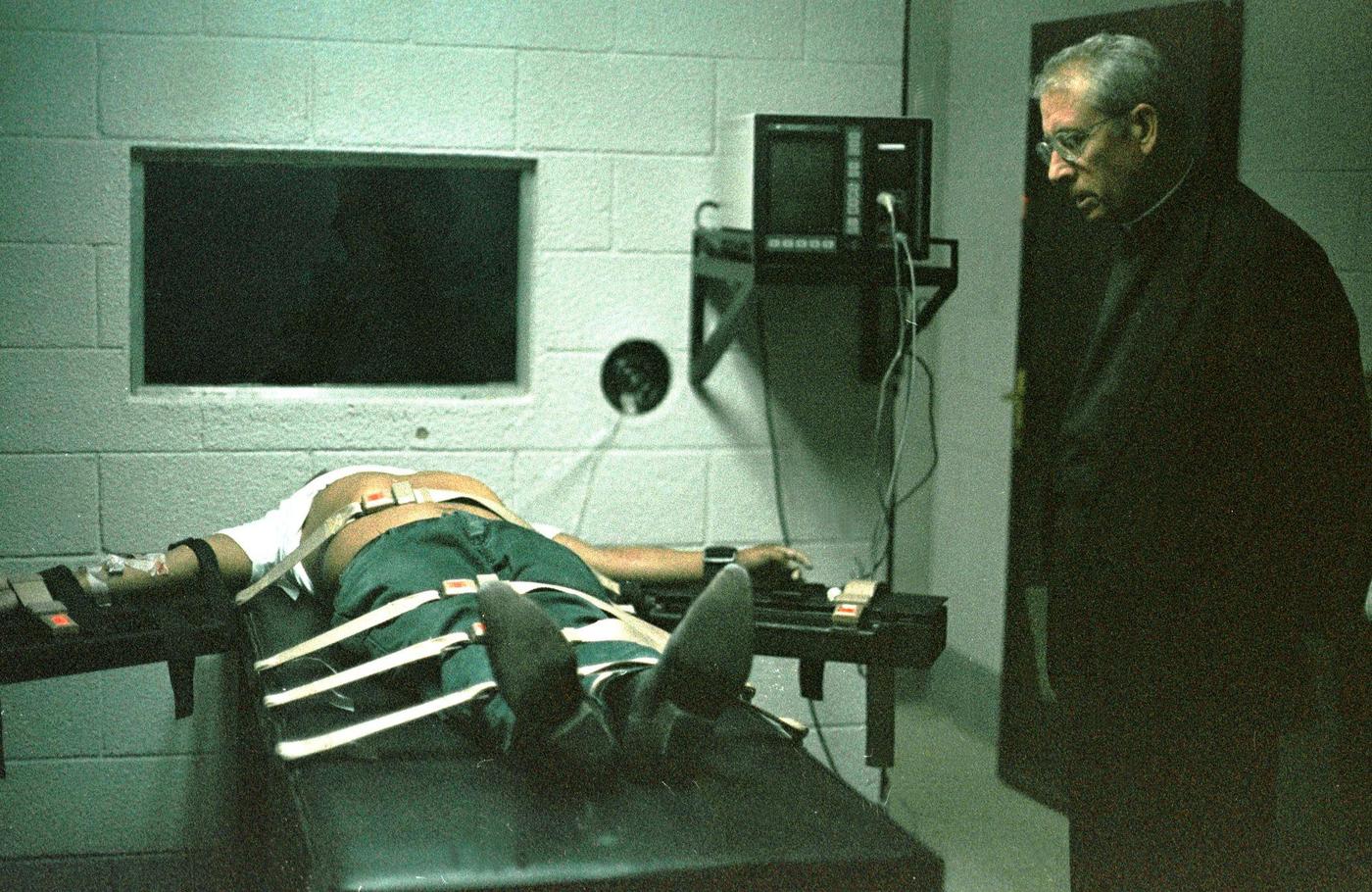

Among the arguments he cited were degrading and inhumane methods of state-sanctioned killing, defective sentencing processes in the criminal justice system, the possibility of judicial error, and the emergence of detention systems that could secure an offender from society and potentially rehabilitate him.

“The new text, following the footsteps of the teaching of John Paul II in ‘Evangelium Vitae,’ affirms that ending the life of a criminal as punishment for a crime is inadmissible because it attacks the dignity of the person, a dignity that is not lost even after having committed the most serious crimes,” he said.

A question of consistency?

The change in the Catechism has renewed a vigorous engagement between Catholic defenders and opponents of the death penalty, who contend their position is more consistent with the Church’s deposit of faith, contained in sacred Scripture and Tradition.

“For me, it’s simply beyond the authority of any particular pope to say that conditions are now such that [capital punishment] is no longer necessary anywhere in the world,” Robert Royal, president of the Faith and Reason Institute in Washington, D.C., told Angelus News.

“It’s like saying that lethal use of force by police, or war, are intrinsically immoral. … But human nature has not changed, and neither have some hard necessities in national and international affairs.”

Edward Feser, a Catholic philosopher who teaches at Pasadena City College and is co-author of “By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed,” a defense of the Catholic death penalty tradition, told Angelus News he believed the new Catechism language had a measure of ambiguity that left unresolved the question whether the death penalty was “inadmissible” by virtue of conditions that could change, or whether the death penalty was “in principle” never justifiable.

Feser said he was concerned about statements that would imply the Church had historically endorsed an intrinsically evil practice.

He argued the change could undermine the teaching authority of the Church and its claim to infallibility, given the justification for the death penalty in the Old and New Testaments, as well as the teachings of a number of the Church Fathers, and the medieval tradition.

“You don’t need to be in favor of capital punishment to worry this revision has gone too far,” he said. If the doctrine on the death penalty can change, he said, why not teachings on marriage, or the priesthood?

Development and continuity

However, the development on capital punishment is consistent with other kinds of developments in Church teaching, such as that on slavery, explained David Cloutier, associate professor of moral theology and ethics at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.

Cloutier explained the Catholic Church now condemns slavery as an “intrinsic evil” — something Pope John Paul declared emphatically in “Veritatis Splendor” (“The Splendor of Truth”) — even though in St. Paul’s time, the Church tolerated slavery while insisting on the dignity of the human person.

Over the centuries, however, the Church reflected on its fundamental doctrines, such as the dignity of the human person as created in God’s image and likeness, and began to confront the violence done to human persons by treating them as property.

The Church engaged in messy, pitched debates in the 16th century over chattel slavery, and by the 19th century concluded slavery was fundamentally incompatible with the dignity of the human person — still, it took the Civil War to force the entire U.S. Church to embrace Rome’s teaching.

Cloutier said the Church’s fundamental test for whether doctrine develops authentically is whether it moves closer to Jesus Christ’s teaching in the gospel.

“The teaching against capital punishment allows us to witness more deeply to the dignity of every human person,” he said.

Cloutier pointed out that Christ also overturned allowances God made for divorce in the Torah — by restoring God’s original plan in Genesis. Likewise, the Church can point to Christ’s refusal in the gospel to condemn a woman to death as prescribed by Levitical laws.

But as the change to the Catechism meets some of its strongest resistance in the U.S. (one of the few remaining countries in the world to allow the death penalty), the debate is also serving to shed light on the Church’s teaching on the nature of justice itself.

According to the Catechism, punishments by legitimate public authorities must be “proportionate to the gravity of the offense,” the primary goal must be “redressing the disorder introduced by the offense,” they should defend the public order and people’s safety, and seek to correct the guilty party as far as possible.

Feser argued that the death penalty rightly affirms the retributive nature of justice as a proportional response to the most heinous crimes, and provides a reference point for punishments applied to lesser crimes.

However, Robert George, McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence at Princeton University and natural law theorist, told Angelus News that “Evangelium Vitae” excludes retribution as a valid reason for the death penalty.

Although St. Thomas Aquinas argued for this position, George said it was inconsistent with the Church’s doctrine against the direct killing of human beings. Pope John Paul’s encyclical corrects that error by allowing the state to act in self-defense against an ongoing aggressor.

Human life is off limits, because it is essential to human nature. But George said retributive justice is met by taking away liberty and property, which a human being can live without.

Nevertheless, George said the Church has not proposed infallible teaching on the death penalty. Even the revised Catechism language, he said, only rises to the level of authoritative teaching, meaning it requires the faithful’s assent as outlined in “Lumen Gentium” (“Light for the Nations”).

“This revision is not infallibly proposed either,” he said, unlike other moral evils, such as slavery, abortion and euthanasia.

The revised Catechism teaching is meant to inform faithful consciences, but George said a person who cannot accept the death penalty is not “an enemy of the faith.”

For these reasons, neither George nor Feser expected any serious proposal that death penalty advocates would be denied Holy Communion for dissenting on the Catechism — particularly when it is rarely invoked for supporters of abortion.

A culture of mercy

The Church is looking toward the abolition of the death penalty as a means to send a signal about the sanctity of human life.

Archbishop José H. Gomez of Los Angeles noted the death penalty today sends “no moral signal” about the sanctity of life, because society is awash with killing, from neighborhood violence to an entertainment that constantly involves murders.

“The Church today is pointing us in a different direction,” he said. “Showing mercy to those who do not ‘deserve’ it, seeking redemption for persons who have committed evil, working for a society where every human life is considered sacred and protected — this is how we are called to follow Jesus Christ and proclaim his gospel of life in these times and in this culture.”

Pelke extended his forgiveness to Cooper about 3 1/2 months after her death sentence was handed down in 1986. He knew his grandmother wanted him to have “love and compassion.”

“The death penalty has nothing to do with healing,” he said. “We promote forgiveness as the way to heal.”

Cooper eventually was released after 30 years in prison — but the mercy Pelke extended was not reciprocated by society when she re-emerged.

Rejected by her own mother and turned away from the Church — the very place Ruth Pelke wanted her to be — Cooper took her own life two weeks before Pelke could legally contact her.

“She felt people would never forget what she did — even though she paid her time.”

Peter Jesserer Smith is a staff writer for EWTN’s National Catholic Register, and a frequent contributor to Angelus.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $25! For less than 50 cents a week, get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!